Bellezza who reviews at Dolce Bellezza (click on words or image below to visit) and reads a lot of interesting literary and translated fiction, recently invited me to join her and a few others to read Two Serious Ladies by Jane Bowles.

I didn’t know anything about the book, but I liked the idea of a January readalong, the last one I participated in was Pushkin’s Eugene Onegin in January 2014 and it became one of my Top Reads of 2014!

Background

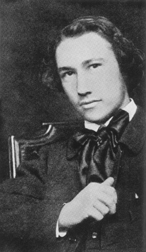

Jane Bowles was married to the composer, writer and translator Paul Bowles (author of the 1949 classic, post-colonial alienation and existential despair novel The Sheltering Sky). They were part of avant-garde literary circles in their home town of New York and adopted homes of Paris, Mexico and Tangiers, known as well for their bohemian lifestyle as their literary success’.

Jane Bowles (born in New York City, Feb 1917) wrote one novel, a play and six short stories. The novel Two Serious Ladies, though panned at the time, (critic Edith Walton writing in the Times Book Review didn’t understand it, calling it ‘senseless and silly’), became regarded as a modernist, cult classic, helped when Tennessee Williams named it his favourite book.

Jane Bowles (born in New York City, Feb 1917) wrote one novel, a play and six short stories. The novel Two Serious Ladies, though panned at the time, (critic Edith Walton writing in the Times Book Review didn’t understand it, calling it ‘senseless and silly’), became regarded as a modernist, cult classic, helped when Tennessee Williams named it his favourite book.

She was famous as the enigmatic and entertaining half of a celebrated couple, for her near permanent writer’s block, her daring attitude to life, and her provocative relationships with women.

Both husband and wife, though dedicated to each other, indulged same-sex relations with others outside their marriage; notable was the relationship Jane Bowles developed with Cherifa, a Moroccan peasant, the only woman in Tangier to run her own market stand. They are photographed; Jane, wearing a white, sleeveless short dress walks on the arm of Cherifa, cloaked in a black niqab, wearing dark sunglasses (said to carry a knife beneath her robes for protection). See the photo in The New Yorker article linked below.

Review

Two Serious Ladies introduces us to two characters Christina Goering, daughter of a powerful industrialist, now a well-heeled spinster, adrift and bored with her comfortable, predictable existence and Frieda Copperfield, married to a man who pursues travel and adventure, dragging his wife (who funds this insatiable desire) out of her comfort zone, to the untouristed, red-lit parts of Panama, where she finds solace and digs her heels in, at the bar/hotel of Madame Quill, befriending the young prostitute Pacifica.

Christina, referred to as Miss Goering and Frieda, Mrs Copperfield, acquaintances, meet briefly at a party and will come together again briefly at the end, both having had separate life-changing adventures, driven by a latent, sub-conscious desire to radically change their situations, both of which come about in a random, haphazard way.

Miss Goering invites a companion Miss Gamelon, to move into her comfortable home and at the party where she encounters Mrs Copperfield, she meets Arnold. Though she doesn’t particularly like either of these characters, when she decides to sell her palatial home and move to a run-down house on a nearby island, they agree to come with her. Neither are enamoured of her decision, to remove them from her previous comforts, which they were quite enjoying.

“In my opinion,” said Miss Gamelon, “you could perfectly well work out your salvation during certain hours of the day without having to move everything.”

“The idea,” said Miss Goering, “is to change first of our own volition and according to our own inner promptings before they impose completely arbitrary changes on us.”

Once on the island, still restless, she abandons her invitees and takes the ferry to the mainland, opening herself up to whatever random encounters await her, as if seeking her destiny or some kind of understanding through a series of desperate and reckless acts.

Jane Bowles

Mrs Copperfield seems less to seek out the depraved, than be attracted by a perceived sense of belonging, she spurns the comfortable, pretentious trappings of the Hotel Washington, declines to go walking in the jungle with her husband and instead takes the bus back to the women she has met at the Hotel les Palmas whom she feels an affinity with, despite their lives of poverty and prostitution being so far removed from her own. She recognises they possess a kind of freedom and strength she lacks; in their presence, she begins to feel energised and empowered.

It is a strange book at first, it requires finishing and reflecting upon to figure out what it was all about. It is recounted in a straight forward style, we observe the actions of the two women without reflection on their part, making it necessary to unravel their intentions, which inevitably becomes a matter of reader interpretation, to find the meaning, if indeed there is any.

For me, it was clear the women lacked something significant in their lives, in their existence, even if they were unable to articulate it or even search appropriately for it, they sensed something missing in their lives of privilege and sought it among the downtrodden. They were experiencing an existential crisis.

In terms of style, the writing has been described as elliptical prose, a term I looked up, coined in 1946 by Frederick Pottle who used elliptical to refer to a kind of pure poetry that omits prosaic information, providing the possibility of intensity through obscurity and elimination.

@Jimthomsen on twitter asked the same question and got this response:

@Jimthomsen words that burn about 400 calories an hour without putting too much strain on the knees?

— Beth Jusino (@bethjusino) October 10, 2015

Meaning, there’s much that isn’t said or thought or written and more that might be implied, discovered between the lines. A form of literary diet perhaps? I do prefer plain language.

Bowles takes two female characters from a similar social class (similar to her own) dissecting a woman’s presence and existence in society in a form of confrontational daring that was liable to elicit both scorn and eye-brow raising in her own time and continues to provoke a certain amount of bemusement in our own.

“I know I am as guilty as I can be, but I have my happiness which I guard like a wolf, and I have authority now and a certain amount of daring, which I never had before.” – Mrs Copperfield

Reading it alongside the life of Jane Bowles, was a pleasure, I enjoyed reading it and taking the extra time to understand the context within which it was written.

Thanks Bellezza for the invitation, I look forward to reading everyone else’s reviews!

Links

The Madness of Queen Jane – Article in The New Yorker, by Negar Azimi June 12, 2014

A Short Biography of Jane Bowles by Millicent Dillon

Other Reviewers Reading & Reviewing Two Serious Ladies – Scott, Frances, Dorian, and Laurie