The 2025 Booker Prize longlist was announced last week, 13 novels were chosen from 153 submitted, celebrating long-form literary fiction by writers of any nationality written in English, published in the UK and/or Ireland between 1 October 2024 and 30 September 2025.

There are two debut novelists among the nine authors appearing on the list for the first time. Indian author Kiran Desai is listed, having won the prize 19 years ago with The Inheritance of Loss and Malaysian author Tash Aw is listed for the third time.

13 Novels, A Booker Dozen

The longlisted titles are:

- Love Forms by Claire Adam (Trinidad)

- The South by Tash Aw (Taiwan/Malaysia)

- Universality by Natasha Brown (UK)

- One Boat by Jonathan Buckley (UK)

- The Loneliness of Sonia and Sunny by Kiran Desai (India/US)

- Audition by Katie Kitamura (US)

- The Rest of Our Lives by Benjamin Markovits (US/UK)

- The Land in Winter by Andrew Miller (UK)

- Endling by Maria Reva (Ukraine/Canada)

- Flesh by David Szalay (Canada/Austria)

- Seascraper by Benjamin Wood (UK)

- Misinterpretation by Ledia Xhoga (Albania/US)

- Flashlight by Susan Chow (US)

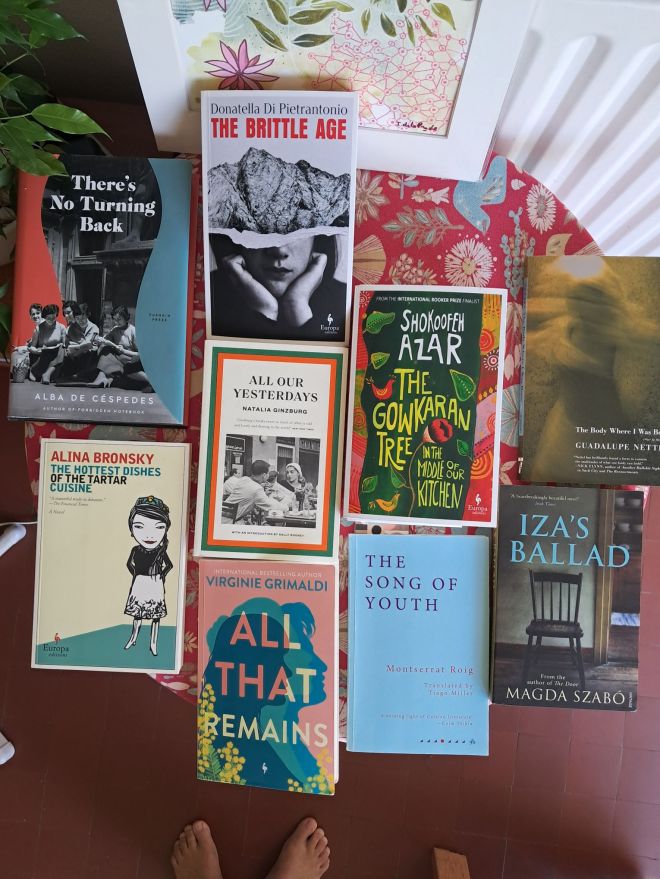

It’s an interesting and very British list compared to other years, and a lot more experimental in style than straight forward traditional storytelling, though that’s to be expected from a literary prize. Coming in August, for me it competes with my wishing to read women in translation for #WITMonth.

Irish Recommendations & Cross Cultural Leanings

After a quick glimpse at the titles the first one that stood out for me was Love Forms by Trinidadian author Claire Adam as I first heard it discussed on The Irish Times Women’s Podcast Summer Reading Recommendations episode and was very tempted. One of my favourite podcasts, their bookclub is fabulous, all the more so, for the host Róisín Ingle’s mother Ann Ingle being part of it (she talks about and recommends Flesh by David Szalay another longlisted title), and adds an interesting mother-daughter dynamic and inter-generational exchange and perspective to the club – and she can’t see, so all her reading is via audio book.

I’m also interested in The Loneliness of Sonia and Sunny by Kiran Desai because it’s a cross cultural story, although I’m not in a rush to read a 600 page novel at present. And Endling sounds interesting, comparisons being made to Percival Everett and George Saunders are both intriguing and promising.

What It’s About & the Judges’ Comment

Below is a summary book description and judges’ comment:

A heart-aching novel of a mother’s search for the daughter she left behind a lifetime ago.

Trinidad, 1980: Dawn Bishop, 16, leaves home and journeys across the sea to Venezuela. She gives birth to a baby girl and leaves her with nuns to be given up for adoption. Dawn tries to carry on with her life; a move to England, marriage, career, two sons, a divorce – but through it all, she still thinks of the child she left, of what might have been.

40 years later, a woman from an internet forum gets in touch saying she might be Dawn’s daughter, stirring up a mix of feelings: could this be the person to give form to the love and care Dawn has left to offer?

‘Claire Adam returns to Trinidad for her sophomore novel. We first meet Dawn, a pregnant 16 year-old, on a clandestine journey across the sea to Venezuela. There, she gives birth and returns home without the baby, just as her parents had prescribed. Now, at 58, Dawn is the divorced mother of two adult men, but the loss of the baby girl consumes her every move. The story, heartbreaking in its own right, comes second to its narration. Dawn’s voice haunts us still, with its beautiful and quiet urgency. Love Forms is a rare and low-pitched achievement. It reads like a hushed conversation overheard in the next room.’

The South by Tash Aw (Taiwan/Malaysia)

A radiant novel about family, desire and what we inherit, and the longing that blooms between two boys over the course of one summer.

When his grandfather dies, Jay travels south with his family to the property he left them, a once flourishing farm fallen into disrepair. The trees are diseased, the fields parched from months of drought. Still, Jay’s father Jack, sends him out to work the land. Over the course of hot, dense days, Jay finds himself drawn to Chuan, son of the farm’s manager, different from him in every way except for one.

Out in the fields, and on the streets into town, the charge between the boys intensifies. At home, other family members confront their regrets, and begin to drift apart. Like the land around them, they are powerless to resist the global forces that threaten to render their lives obsolete.

Sweeping and intimate, The South is a story of what happens when private and public lives collide. It is the first in a quartet of novels that form Tash Aw’s portrait of a family navigating a period of change.

‘It’s summertime in the 1990s and rural Malaysia is hot. Teenager Jay and his family leave their home of Kuala Lumpur to work on a farm in the Johor Bahru countryside. There, Jay meets Chuan, who opens Jay up to friendship, illicit pastimes, and a deeper understanding of his sexuality. To call The South a coming-of-age novel nearly misses its expanse. This is a story about heritage, the Asian financial crisis, and the relationship between one family and the land. The South is the first instalment of a quartet, and we’re so pleased that there is more to come.’

The Loneliness of Sonia and Sunny by Kiran Desai (India/US)

A spellbinding story of two people whose fates intersect and diverge across continents and years – an epic of love & family, India & America, tradition & modernity

When Sonia and Sunny first glimpse each other on an overnight train, they ar captivated, and embarrassed their grandparents had once tried to matchmake them, a clumsy meddling that served to drive Sonia and Sunny apart.

Sonia, an aspiring novelist who completed her studies in the snowy mountains of Vermont, has returned to India, haunted by a dark spell cast by an artist she once turned to. Sunny, a struggling journalist resettled in New York City, attempts to flee his imperious mother and the violence of his warring clan. Uncertain of their future, Sonia and Sunny embark on a search for happiness as they confront the alienations of our modern world.

The Loneliness of Sonia and Sunny is the tale of two people navigating the forces that shape their lives: country, class, race, history, and the bonds that link one generation to the next. A love story, a family saga, and a rich novel of ideas, it is an ambitious and accomplished work by one of our greatest novelists.

‘This novel about Indians in America becomes one about westernised Indians rediscovering their country, and in some ways a novel about the Indian novel’s place in the world. Vast and immersive, the book enfolds a magical realist fable within a social novel within a love story. We loved the way in which no detail, large or small, seems to escape Desai’s attention, every character (in a huge cast) feels fully realised, and the writing moves with consummate fluency between an array of modes: philosophical, comic, earnest, emotional, and uncanny.’

Flashlight Written by Susan Choi (US)

A thrilling, globe-spanning novel that mines questions of memory, language, identity and family

One evening, 10-year-old Louisa and her father take a walk out on the breakwater. They are spending the summer in a coastal Japanese town while her father Serk, a Korean émigré, completes an academic secondment from his American university. When Louisa wakes hours later, she has washed up on the beach and her father is missing, probably drowned.

The disappearance of Louisa’s father shatters their small family. As Louisa and her American mother return home, this traumatic event reverberates across time and space, as the mystery of what happened unravels.

Flashlight moves between the post-war Korean immigrant community in Japan, to suburban America, and the North Korean regime, to tell the astonishing story of a family swept up in the tides of 20th-century history.

‘Flashlight is a sprawling novel that weaves stories of national upheavals with those of Louisa, her Korean Japanese father, Serk, and Anne, her American mother. Evolving from the uncertainties surrounding Serk’s disappearance, it is a riveting exploration of identity, hidden truths, race, and national belonging. In this ambitious book that deftly criss-crosses continents and decades, Susan Choi balances historical tensions and intimate dramas with remarkable elegance. We admired the shifts and layers of Flashlight’s narrative, which ultimately reveal a story that is intricate, surprising, and profound.’

An exhilarating, destabilising novel that asks whether we ever really know the people we love

Two people meet for lunch in a Manhattan restaurant. She’s an accomplished actress in rehearsals. He’s attractive, troubling, young – young enough to be her son. Who is he to her, and who is she to him?

In this compulsive, brilliantly constructed novel, two competing narratives unspool, rewriting our understanding of the roles we play every day – partner, parent, creator, muse – and the truths every performance masks, especially from those who think they know us most intimately.

‘This novel begins with an actress meeting a young man in a Manhattan restaurant. A surprising, unsettling conversation unfolds, but far more radical disturbances are to come. Aside from the extraordinarily honed quality of its sentences, the remarkable thing about Audition is the way it persists in the mind after reading, like a knot that feels tantalisingly close to coming free. Denying us the resolution we instinctively crave from stories, Kitamura takes Chekhov’s dictum – that the job of the writer is to ask questions, not answer them – and runs with it, presenting a puzzle, the solution to which is undoubtedly obscure, and might not even exist at all.’

A twisty, slippery descent into the rhetoric of truth and power

‘Remember – words are your weapons, they’re your tools, your currency.’

Late one night on a Yorkshire farm, a man is bludgeoned with a solid gold bar. A plucky young journalist sets out to uncover the truth, connecting the dots between an amoral banker landlord, an iconoclastic columnist, and a radical anarchist movement. She solves the mystery, but her exposé raises more questions than it answers.

Through a voyeuristic lens, Universality focuses on words: what we say, how we say it, and what we really mean. The follow-up novel to Natasha Brown’s Assembly is a compellingly nasty celebration of the spectacular force of language. It dares you to look away.

‘Natasha Brown’s Universality is a compact yet sweeping satire. Told through a series of shifting perspectives, it reveals the contradictions of a society shaped by entrenched systems of economic, political, and media control. Brown moves the reader with cool precision from Hannah, a struggling freelancer, through to Lenny, an established columnist, unfurling through both of them an examination of the ways language and rhetoric are bound with power structures. We were particularly impressed by the book’s ability to discomfit and entertain, qualities that mark Universality as a bold and memorable achievement.’

Endling by Maria Reva (Ukraine/Canada)

An unforgettable debut novel about the journey of three women and one extremely endangered snail through contemporary Ukraine

Ukraine, 2022. Yeva is a maverick scientist who scours the forests and valleys, trying and failing to breed rare snails while her relatives urge her to settle down and start a family. What they don’t know: Yeva dates plenty of men – not for love, but to fund her work – entertaining Westerners who take guided romance tours believing they’ll find docile brides untainted by feminism.

Nastia and her sister, Solomiya, are also entangled in the booming marriage industry, posing as a hopeful bride and her translator while secretly searching for their missing mother, who vanished after years of fierce activism against the romance tours. So begins a journey across a country on the brink of war: three angry women, a truckful of kidnapped bachelors, and Lefty, a last-of-his-kind snail with one final shot at perpetuating his species.

‘Endling shouldn’t be funny, but it is – very. Set in Ukraine just as Putin invades, it features three young women, on two different missions, in one vehicle. Structurally wild and playful, Endling is also heart-rending and angry. It examines colonialism, old and neo, the role of women, identity, power and powerlessness, and the very nature of fiction-writing. Maria Reva also tells a riveting, unique story; the shock is that this is her first novel. It’s a book about the world now, and about three unforgettable women, Yeva, Nastia and Solomiya, travelling together in a mobile lab. The endling, by the way, is a snail.’

A mesmerising portrait of a young man confined by his class and the ghosts of his family’s past, dreaming of artistic fulfilment

Thomas lives a slow, deliberate life with his mother in Longferry, working his grandpa’s trade as a shanker. He rises early to take his horse and cart to the grey, gloomy beach and scrape for shrimp, spending the afternoon selling his wares, trying to wash away the salt and scum, pining for Joan and rehearsing songs on his guitar. At heart, he is a folk musician, but it remains a private dream.

When a striking visitor turns up, bringing the promise of Hollywood glamour, Thomas is shaken from the drudgery of his days and imagines a different future. But how much of what the American claims is true, and how far can his inspiration carry Thomas? Haunting and timeless, a story of a young man hemmed in by circumstances, striving to achieve fulfilment far beyond the world he knows.

‘Seascraper seems, at first, to be a beautifully described account of the working day of a young man, Thomas Flett, who works as a shanker in a north of England coastal town, scraping the Irish Sea shore for scrimps. And it is that: the details of the job and the physicality of the labour are wonderfully captured by Benjamin Wood. But this novel becomes much more than that. It’s a book about dreams, an exploration of class and family, a celebration of the power and the glory of music, a challenge to the limits of literary realism, and – stunningly – a love story.’

Artfully constructed, absorbing and insightful, One Boat grapples with questions of identity, free will, guilt and responsibility

On losing her father, Teresa returns to a small Greek coastal town – the same place she visited when grieving her mother nine years ago. She immerses herself in the life of the town, observing the inhabitants, a quiet backdrop for reckoning with herself. An episode from her first visit resurfaces – her encounter with John, a man struggling to come to terms with the violent death of his nephew.

Teresa encounters people she met before: Petros, an eccentric mechanic, whose life story may or may not be part of John’s; the beautiful Niko, a diving instructor; and Xanthe, a waitress in one of the cafés. They talk about their longings, regrets, the passing of time, their sense of who they are.

‘Following the death of her father, Teresa returns to the small coastal town in Greece she first visited when her mother died nearly a decade before. From this scenario, tacking between the events of the second trip and memories of the first, Buckley creates a novel of quiet brilliance and sly humour, packed with mystery and indeterminacy. The way in which the book interleaves Teresa’s relationship to her mother, her involvement in an amateur murder investigation, and an account of a love affair, raises questions about grief, obsession, personhood and human connectivity we found to be as stimulating as they are complex.’

Flesh by David Szalay (Canada/Austria)

A propulsive, hypnotic novel about a man who is unravelled by a series of events beyond his grasp

Fifteen-year-old István lives with his mother in an apartment complex in Hungary. New to the town and shy, he is unfamiliar with social rituals at school and becomes isolated, with his neighbour – a woman close to his mother’s age – his only companion. Their encounters shift into a clandestine relationship that István barely understands, as his life spirals out of control.

As the years pass, he is carried upwards on the century’s tides of money and power, moving from the army to the company of London’s super-rich, with his own competing impulses for love, intimacy, status and wealth winning him riches, until they threaten to undo him completely. Flesh asks profound questions about what drives a life: what makes it worth living, and what breaks it.

‘David Szalay’s fifth novel follows István from his teenage years on a Hungarian housing estate to borstal, and from soldiering in Iraq to his career as personal security for London’s super-rich. In many ways István is stereotypically masculine – physical, impulsive, barely on speaking terms with his own feelings (and for much of the novel barely speaking: he must rank among the more reticent characters in literature). But somehow, using only the sparest of prose, this hypnotically tense and compelling book becomes an astonishingly moving portrait of a man’s life.’

The Land in Winter by Andrew Miller (UK)

A masterful, page-turning examination of the minutiae of life and a dazzling chronicle of the human heart

December 1962, the West Country. Local doctor Eric Parry, mulling secrets, sets out on his rounds, while his pregnant wife sleeps on in their cottage. Across the field, funny, troubled Rita is also asleep, her head full of images of a past her husband prefers to ignore. He’s been up for hours, tending to the needs of the small dairy farm where he hoped to create a new version of himself, a project that’s faltering.

When the ordinary cold of an English December gives way to violent blizzards, the two couples find their lives unravelling. Where do you hide when you can’t leave home? And where, in a frozen world, can you run to?

Misinterpretation by Ledia Xhoga (Albania/UK)

Ledia Xhoga’s ruminative debut interrogates the darker legacies of family and country, and the boundary between compassion and self-preservation

In present-day New York City, an Albanian interpreter reluctantly agrees to work with Alfred, a Kosovar torture survivor, during his therapy sessions. Despite her husband’s cautions, she becomes entangled in her clients’ struggles: Alfred’s nightmares stir up buried memories, and an impulsive attempt to help a Kurdish poet leads to a risky encounter and a reckless plan.

As ill-fated decisions stack up, jeopardising the narrator’s marriage and mental health, she travels to reunite with her mother in Albania, where her life in the United States is put into stark relief. When she returns to face the consequences, she must question what is real and what is not.

‘A Kosovan torture survivor requests translation assistance at his therapy sessions. Our narrator, a nameless translator, reluctantly agrees. But Alfred’s account of his experiences conjures hidden memories that seep into her psyche, forcing her to question her marriage and her place in the world. This is a story of a woman saddled between her Albanian past and her New York present. It explores the way that language is kept in our bodies, how it can reveal truths we aren’t ready to hear. Misinterpretation subtly blurs the distinction between help and harm. We found it propulsive, unsettling, and strangely human.’

The Rest of Our Lives by Ben Markovits (US/UK)

An unforgettable road trip of a novel about getting older, and the challenges of long-term marriage

What’s left when your kids grow up and leave home? When Tom Layward’s wife had an affair, he resolved to leave her as soon as his youngest turned 18. Twelve years later, while driving her to start university, he remembers his pact. Also he’s on the run from health issues, and the fact he’s been put on leave at work after students complained about the politics of his law class – a detail he hasn’t told his wife.

After dropping Miriam off, he keeps driving, with the vague plan of visiting various people from his past – an old college friend, his ex-girlfriend, his brother, his son – on route, maybe, to his father’s grave. Pitch perfect, quietly exhilarating, moving, The Rest of Our Lives is a novel about family, marriage and moments that may come to define us.

‘When Tom Layward’s wife cheated on him, he stayed for the children but promised to leave when his youngest turned eighteen. Twelve years later, Tom drops his daughter off at college, but instead of driving back to New York he heads west. What follows is a remarkably satisfying road trip full of strangers, friends, and self-discovery. It’s clear author Ben Markovits has spent time teaching. This novel speaks like a much-loved professor, one whose classes have a terribly long waitlist. It’s matter of fact, effortlessly warm, and it uses the smallest parts of human behaviour to uphold bigger themes, like mortality, sickness, and love. The Rest of Our Lives is a novel of sincerity and precision. We found it difficult to put it down.’

What Do You Think?

Are you tempted by anything on the list or have you read any of these titles? Let us know in the comments below.

If you’re not sure, Take the Quiz and see what your preferences suggest. I took the quiz and it suggested I read Flesh by David Szalay. Not sure about that! But Ann Ingle did recommend it.