International Women’s Day

Journée internationale des droits des femmes 2022

My calendar tells me that today is the journée internationale des droits des femme (I like that in French it focuses on the rights on women, somewhat lost in translation in English) so I’ve been thinking about what to share.

As often is the case when I ask myself an open question, my mind responds by connecting various other things I’ve noted recently together, creating a common thread.

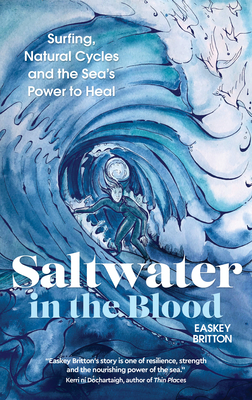

An article about women surfing in Sri Lanka prompted me to choose Easkey Britton’s book Saltwater in the Blood to read for Reading Ireland Month and it’s the perfect choice for International Women’s Day.

Women Surfing in Sri Lanka

A couple of days ago there was a wonderful article in the Guardian, ‘When I surf I feel so strong’: Sri Lankan women’s quiet surfing revolution by Hannah Ellis-Peterson about the desire of Shamali Sanjaya who grew up in a fishing village, to experience riding the waves like her brother and father whom she would sit and watch enviously.

Photo by K. Gonzalez-Keola Pexels.com

When a friend knocked on her door one day inviting her to go surfing, she could hold it back no more, that longing – like the title of Irish pro surfer Easkey Britton’s book alludes to – was indicative of saltwater in the blood. She was a natural surfer.

“When I surf, it is such a happy feeling for me,” she said. “I am filled with this energy, I feel so strong. Life is full of all these headaches and problems, but as soon as I get into the water, I forget about it all.”

Not content to keep her passion to herself, she persevered through disapproval and in 2018 set up the Arugam Bay Girls Surf Club, members, ranging from ages 13 to 43. Despite having broken through many local taboos amid accusations of trying to change the culture, many women still face a backlash from their families and communities; however their perseverance has also brought a new lease of life and healing to others.

Book Review and An Obsession With the Sea

I bought this book because I am a sea creature, a lover of the sea, its secrets and legends. I grew up on the wild west coast of New Zealand, near the volcanic rock and black sand beaches of Port Waikato and loved nothing more than going out past the breakers into the big swell of the huge waves there, being lifted up and down and eventually body surfing the wave back in. I loved it.

The coastline is notoriously wild and unfriendly, waves break against rugged cliffs, and the sea in some parts is slowly reclaiming the black sand dunes and dwellings that humans built.

There is something mesmerising about the sea and Easkey Britton’s story shares her physical and intellectual pursuit of it, her mindful practice in relation to it, eventually learning how to awaken to the more feminine element of her psyche in her relation to it with others.

The Irish Coast and Big Wave Surfing

Saltwater in the Blood is an account of her lifelong relationship with the sea, surfing and the rugged coastline of Ireland’s western coast. Complimented by her beautiful illustrations, as on the cover, it is perhaps the nearest thing to experiencing surfing without getting in the water!

She writes about surfing, her connection with the sea and the Irish coast, natural cycles, the ebb and flow of life and learning to let go.

Right from her early school days, if the tide was out far enough the seafront provided a shortcut to school. Her father surfed and painted and she joined the boys in the water, learning to surf at a young age and becoming a pro champion surfer who toured the world catching waves.

In the first part of the book she shares how she focused on surfing, following a well trodden path, overcoming fear, learning to read the signs, pushing her physical and mental limits as each level of difficulty was conquered, trying to stay grounded and safe, while riding and being tossed by the waves.

Connect Not Conquer

However, over time, she learned to regard the sea in a different way and began the process of letting go of the need to compete and the heightened awareness that being one of the only girls in the water carried with it. She began the process of moving away from competition towards collaboration (a process that Riane Eisler writes about in Nurturing Our Humanity).

Though she recalls the excitement of learning to tow-surf (pulled behind a jet ski in order to access big waves a paddle surfer can’t get to) and the thrill of surfing the giant waves nearby at Mullaghmore (see Conor Maguire riding a 60-foot Monster Wave), an invitation to travel to far flung places to write about surfing in countries and cultures where it is little known, provides her an opportunity to learn more from what the sea offers, and the unique experience of being in the company of women and their shared relationship to the sea.

Surfing in Iran

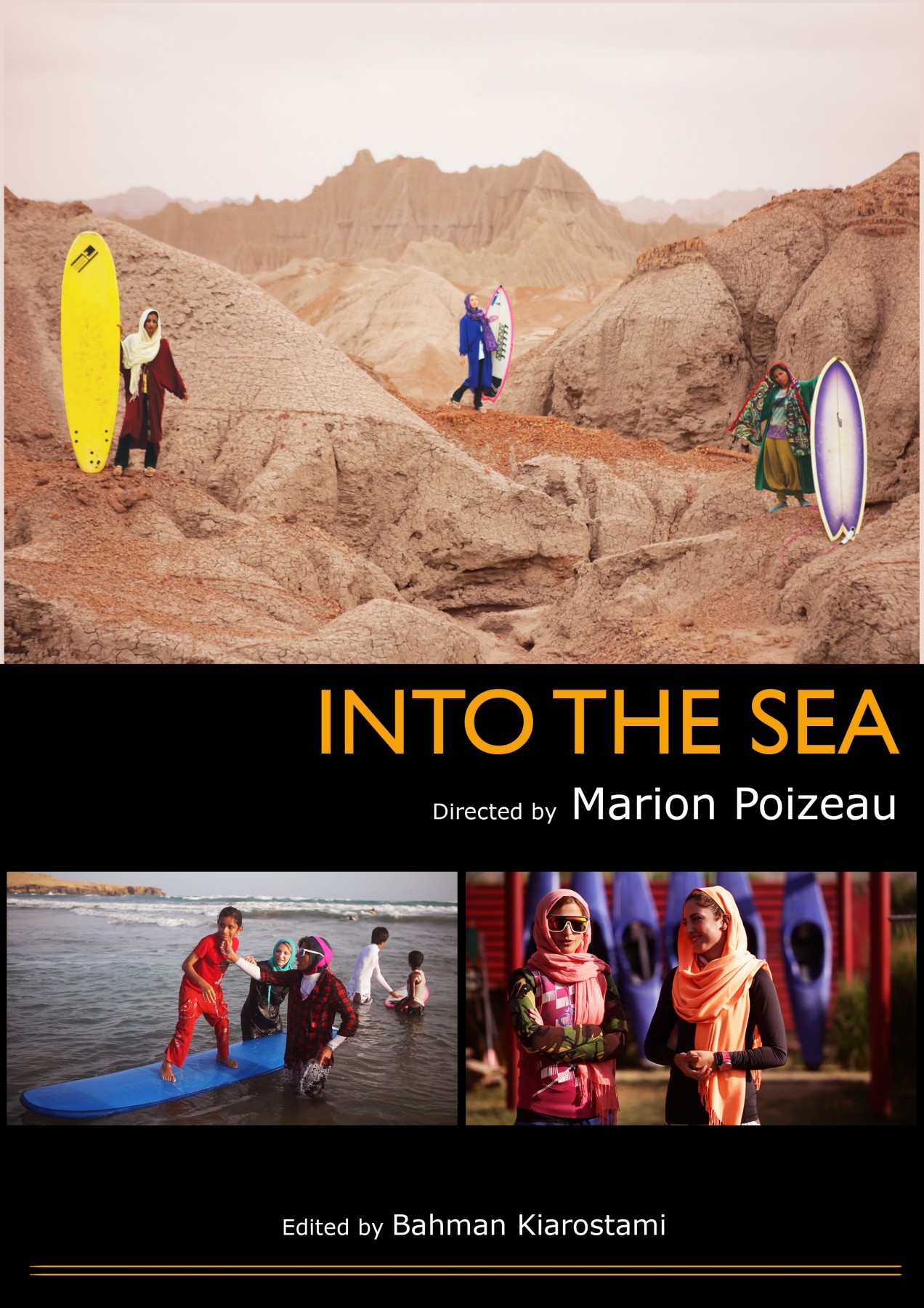

One of the most interesting chapters in book for me, was the time she spent in Sistan-Baluchistan in Iran, .

It was a land not known for its surf-exposed coastline. A short stretch of coast, about 60 to 80 kilometres, lies in a narrow swell window between Pakistan and the coast of Oman, exposed for a few months of the year during Indian monsoon season. This was a part of Iran that didn’t feature in any travel guides, let alone surf magazines…At first, it was primarily about the waves, like all surf trips -the discovery of waves that maybe no one else had surfed before. But it soon became something much more.

The first trip was captured in a short film by her travelling companion, French filmmaker Marion Poizeau, an effort that she eventually published on YouTube having failed to find a production or TV company to share it. It went viral – MISSION “SURF EN IRAN”! and was the beginning of their adventure, the second time, the story became about connecting with and teaching a local group of Baluch women to surf.

I wanted to understand the challenges and opportunities of being able to do it and how this compared to our notion of surfing as a pursuit that offers a sense of freedom, flow and escapism and how that was translated in the context of somewhere like Iran.

Before climbing on the surfboards, they would do what in effect were warm up exercises, but not of the traditional sportsman type, they would play in the waves and get a feel for the swell and the breakers, preparing themselves by sensing the sea’s mood, harmonising with each other.

Before climbing on the surfboards, they would do what in effect were warm up exercises, but not of the traditional sportsman type, they would play in the waves and get a feel for the swell and the breakers, preparing themselves by sensing the sea’s mood, harmonising with each other.

This change of direction, firstly away from the competitive purpose of surfing and even away from the act of discovery and exploration, towards a meaningful exchange, capable of contributing something meaningful to each others lives, is what I was most impressed by, particularly thinking about that in the context of what today is about, empowering women through sharing knowledge.

It was a breakthrough moment for me personally in terms of how my relationship with surfing and my body truly altered and I realized how much more drawn I was to the connective rather than competitive aspects of surfing and the sea.

Joined by Mona Seraji, a snowboarder and Shahla Yasini, a swimmer and diver, this experience would result in the award winning documentary Into The Sea. Through the eyes of these three women, the viewer experiences the journey from a unique and unusual perspective, full of heart and emotion.

Protect the Ocean

The book ends with a message about looking after the ocean and the responsibility we all have to protect our local water sources.

I also enjoyed that there were so many familiar references to other books I’ve read about the sea or the environment, like Rachel Carson’s The Sea Around Us, botanist Robin Kimmerer’s Braiding Sweetgrass, Anne Morrow Lindbherg’s classic Gift From the Sea and many more.

If you like reading books about the sea and particularly from a woman’s perspective, add this one to your list!

Further Reading

Magic Seaweed’s Hannah Bevan Interviews Easkey Britton On the Power of Saltwater Immersion

Oceanographic Magazine: Living By The Tide by Easkey Britton on Wild Swimming

SilverKris Article, May 2021: The Rise of Sri Lanka’s First Female Surfers by Zinara Rathnayake (with great photos by Tommy Schultz)

Easkey Britton, Author

Easkey Britton Working On Her Book at Fanad Lighthouse, one of the ‘Great Lighthouses of Ireland’

Easkey Britton is a world renowned surfer, marine social scientist, activist, writer and artist passionate about the sea. She contributes her expertise in blue spaces , health and social well-being to national and international research projects.

A life-longer surfer, she channels her passion for surfing and the sea into social change. Her work is deeply influenced by the ocean and the lessons learned pioneering women’s big wave surfing in Ireland.

She is the author of 50 Things To Do Beside the Sea, has published numerous peer-reviewed articles and is a regular columnist at Oceanographic Magazine. She lives on the West Coast of Ireland with her partner and their dog Wolfie – however a picture she shared two days ago in a rock pool indicates there are twins on the way!

Somewhere on a plateau above a small forested village in Poland, near the border with the Czech Republic, lives Janina, except she doesn’t like that name, she insists on being called Mrs Duszejko.

Somewhere on a plateau above a small forested village in Poland, near the border with the Czech Republic, lives Janina, except she doesn’t like that name, she insists on being called Mrs Duszejko.

Dizzy, a former student, now her 30 year old friend, helps with the Blake translations, though is unconvinced by some of her theories concerning astrology and the revenge of animals, bolstered by her having discovered real animal trials, which peaked in 14th to 16th century Europe.

Dizzy, a former student, now her 30 year old friend, helps with the Blake translations, though is unconvinced by some of her theories concerning astrology and the revenge of animals, bolstered by her having discovered real animal trials, which peaked in 14th to 16th century Europe. When he challenges her for going around telling people about those Animals, concerned for her reputation, she is outraged.

When he challenges her for going around telling people about those Animals, concerned for her reputation, she is outraged. Olga Tokarczuk is an Aquarian, a Psychologist and Jungian expert, a Polish essayist and author of nine novels, three short story collections and her work has been translated into forty-five languages.

Olga Tokarczuk is an Aquarian, a Psychologist and Jungian expert, a Polish essayist and author of nine novels, three short story collections and her work has been translated into forty-five languages. This is the novel I have been waiting for Jan Carson to write, for here is a writer who in her ordinary life as an arts facilitator has brought together people from opposite sides in their way of thinking, encouraging them to sit down and write little stories, enabling them to imagine from within the shoes of an(other) – teaching the practice of empathy.

This is the novel I have been waiting for Jan Carson to write, for here is a writer who in her ordinary life as an arts facilitator has brought together people from opposite sides in their way of thinking, encouraging them to sit down and write little stories, enabling them to imagine from within the shoes of an(other) – teaching the practice of empathy.

1.

1.  2.

2.  3.

3.  4.

4.  5.

5.  1.

1.  2.

2.  3.

3.  4.

4.  5.

5.

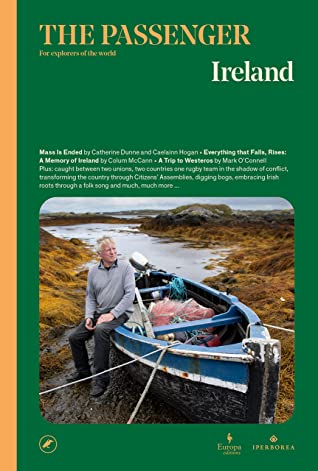

And perhaps most of all, I’m very excited about this upcoming collection of illustrated essays, photography, art and reporting,

And perhaps most of all, I’m very excited about this upcoming collection of illustrated essays, photography, art and reporting,