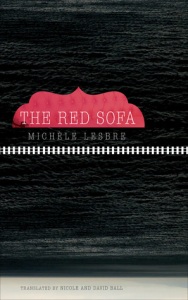

translated by David Ball, Nicole Ball

An Unexpected Trans-Siberian Railway Trip

A French novella that I read in an afternoon, we accompany our Parisian protagonist Anne, on a train journey towards Lake Baikal, in Southern Siberia, a journey she makes on a local train, having spontaneously decided to find out why her friend Gyl is no longer responding to her letters.

For the first six months he had written often, telling me he had time to go fishing for omul in the lake and make kites for children.

And then, silence.

Once on the train and it’s a long journey, she has time to think and recall their friendship, they were lovers many years ago and while she holds no flame for him, the journey allows her to reflect on the highs and lows of their union.

I knew that the return trip is the real journey, when it floods the days that follow, so much so that it creates the prolonged sensation of one time getting lost in another, of one space losing itself in another. Images are superimposed on one another – a secret alchemy, a depth of field in which our shadows seem more real than ourselves. That is where the truth of the voyage lies.

Get To Know Your Neighbour

What she does spend time thinking of, is her recent past and another spontaneous decision, to knock on the door of a neighbour whom she has never seen, an elderly woman.

I had never run into her in the lobby of the building, not on the stairs. I knew all the other people who lived there, or at least their names and faces, but Clémence Barrot remained a mystery. No sounds would ever reach me when I walked by her door, and if I asked questions about her, all I got were laconic answers and knowing looks…A character!

The door is opened by a young girl and peering inside she sees the older woman sitting on a red sofa by a window. As an excuse for her curiosity she mentions there might be noise as she has people coming for dinner that evening. The woman asks her a favour in return for the anticipated inconvenience.

With a big smile, she retorted that she would rather we proceeded differently: for all past dinners, for this one and the next ones, she would only ask in exchange that I occasionally read to her a little, if I had the time.

Passionate French Women Who Faced Death Unflinchingly

Passionate French Women Who Faced Death Unflinchingly

And so we meet some bold French female heroines of the past, sadly a number of whom for their feminist inclinations in the wrong era, lose their lives at the guillotine.

“Tell me about that gutsy girl again,” Clémence Barrot would sometimes ask about Marion de Faouët and her army of brigands. She had, just as I did, a real affection for that child who had not grown up to become a lady’s companion despite all the efforts of the Jaffré sisters. No, she became a leader of men instead, an avenger of Brittany which had been starved during the 1740’s.

A wild beauty, faithful to her village, her loves and her ideals, Marion had been imprisoned several times before dying on the gallows at the age of thirty-eight.

While these stream of consciousness thoughts pass through her mind, various locals enter and exit the train. She is happy to be immersed in the languages of the area and in two books she has brought with her, Dostoevsky’s War and Peace and a book by the philosopher Jankélévitch.

Travel To Exotic Destinations Through Story

Becoming particularly interested in one man whom she can’t communicate with – Igor – she imagines things about him from the little she observes and seeks him out more than one time when he disappears.

I had just read ‘There are encounters with people completely unknown to us who trigger our interest at first sight, suddenly, before a word has even been said…”

It’s an engaging read considering not much happens, but there is just the right mix of action and reflection and indeed, by the end a build up to a couple of dramas and quiet resolution.

I really enjoyed the read and was surprised at how captivated I was by the journey. I do love long train journey’s and hers was such an indulgent whim, that the suspension of what she will encounter is enough to keep the reader interested, and the relationship with her elderly neighbour provides a brilliant counterpoint and empathic adjunct, becoming the more significant event to the ‘thousands of miles’ distraction.

N.B. This was one of the many Seagull Books offered weekly to readers during the period of confinement.

Further Reading

Reviewed by Rough Ghosts

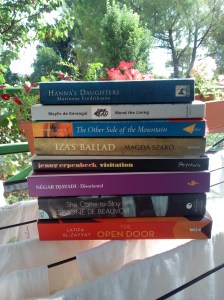

Seagull Books: More of their extensive collection of titles by Women In Translation

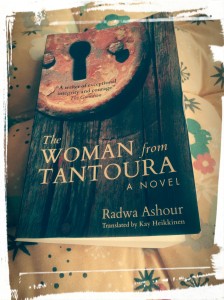

The more I read, the more this novel got its hooks into me. After a while, a pattern begins to emerge, one that is universal. To find a place where one can live authentically, and be at home.

The more I read, the more this novel got its hooks into me. After a while, a pattern begins to emerge, one that is universal. To find a place where one can live authentically, and be at home.

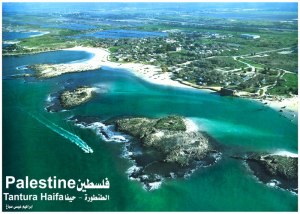

While her mother uses imagination to create a vision of what happened and where the missing are, Ruqayya’s advances then retreats, as the present awakens the past, rarely does she dwell in an idealised future.

While her mother uses imagination to create a vision of what happened and where the missing are, Ruqayya’s advances then retreats, as the present awakens the past, rarely does she dwell in an idealised future. There is no place that quite replaces the childhood environment and home, except perhaps to create one’s own family, and this Raqayya will do, with her son’s and the daughter, a girl Maryam her husband brings home one day from the hospital, adopting her as their own. And in growing things, not the almond tree or the olives, but flowers, a thing of beauty, the damask rose, the bird of paradise.

There is no place that quite replaces the childhood environment and home, except perhaps to create one’s own family, and this Raqayya will do, with her son’s and the daughter, a girl Maryam her husband brings home one day from the hospital, adopting her as their own. And in growing things, not the almond tree or the olives, but flowers, a thing of beauty, the damask rose, the bird of paradise. The reason they are highlighted in August is an attempt to raise awareness of the very narrow choice we give ourselves by only reading books in English, or from one’s own country and to highlight the fact that even when we do read outside our first language, the majority of books published, promoted and reviewed are written by men.

The reason they are highlighted in August is an attempt to raise awareness of the very narrow choice we give ourselves by only reading books in English, or from one’s own country and to highlight the fact that even when we do read outside our first language, the majority of books published, promoted and reviewed are written by men.

She Came to Stay by Simone de Beauvoir

She Came to Stay by Simone de Beauvoir The Other Side of the Mountain by Erendiz Atasü is one of those books I came across in a blog post I read in 2017, a post entitled

The Other Side of the Mountain by Erendiz Atasü is one of those books I came across in a blog post I read in 2017, a post entitled

I’ve attempted to read Visitation about four times and never succeeded in getting past the first few chapters, but this year I persevered as I felt I hadn’t given it a fair chance.

I’ve attempted to read Visitation about four times and never succeeded in getting past the first few chapters, but this year I persevered as I felt I hadn’t given it a fair chance.

On the day when the nation is shocked and grieving after a devastating earthquake, that has destroyed entire villages and resulted in a significant loss of life, I don’t know how appropriate it is to share their literature, perhaps in the case of this particular novel, it serves to put things in perspective.

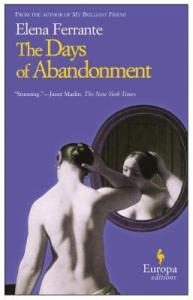

On the day when the nation is shocked and grieving after a devastating earthquake, that has destroyed entire villages and resulted in a significant loss of life, I don’t know how appropriate it is to share their literature, perhaps in the case of this particular novel, it serves to put things in perspective. A national bestseller for almost an entire year, The Days of Abandonment shocked and captivated its Italian public when first published.

A national bestseller for almost an entire year, The Days of Abandonment shocked and captivated its Italian public when first published.