Feeling a little uninspired by recent reads, I decided to check my shelves for what I had in translation, August is WIT Month and my shelves are looking a little depleted in that regard!

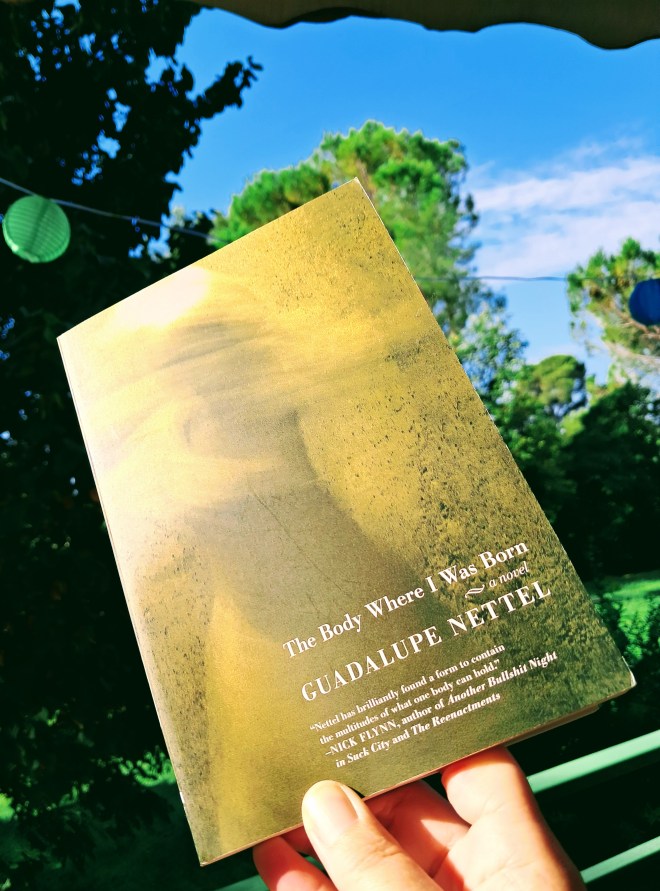

I spotted Guadalupe Nettel’s novel The Body Where I Was Born and remembered how much I adored Still Born (my review here) in 2023, a book that was shortlisted for the International Booker Prize 2023. It’s a compelling exploration by two women into the question of whether or not to have children and how their ideas can change as life happens and circumstances arise that can awaken feelings not born of the mind.

Why Did I Do It, Doctor?

It was the compelling style that made me want to read something else by Nettel and as I began to read The Body Where I Was Born I realised it is semi-autobiographical.

The novel is narrated from the psychotherapist’s chair and so occasionally there will an interruption where the narrator asks a question having recounted yet another episode of their childhood.

The novel is written in five parts, segmenting different parts of childhood and it is effectively a form of coming-of-age, albeit recounted to a therapist.

A Marked Childhood

As with her previous novel and writing style, I was immediately drawn into the narrative, which begins with the author recounting the consequence of having been born with a birthmark covering part of her eye.

The only advice the doctors could give my parents was to wait: by the time their daughter finished growing, medicine would surely have advanced enough to offer the solution they now lacked. In the meantime, they advised subjecting me to a series of annoying exercises to develop, as much as possible, the defective eye.

As a result, school became even more of an inhospitable environment and those measures marking her out for unwanted attention.

Condition and Correct, A Parental Institution

But sight was not my family’s only obsession. My parents seemed to think of childhood as the preparatory phase in which they had to correct all the manufacturing defects one enters the world with, and they took this job very seriously.

Our narrator ponders the harm of parental regimes and how we perpetuate onto the next generation the neuroses of our forebears, wounds we continue to inflict on ourselves.

In addition to these corrections, her parents were keen to adopt some of the prevailing ideas of the time (the seventies) about education, a Montessori school in Mexico City and a sexual education free of taboos and encouraging candid conversations.

Rather than clarifying things, this policy often made things more confusing and distressing for the children and was likely the cause of the rupture of the adults when they adopted a practice much in fashion at the time, the then-famous ‘open-relationship’.

During all the preparatory conversations I had worn the mask of the understanding daughter who reasons instead of reacts, and who would cut off a finger before aggravating her already aggravated parents. Why did I do it, Doctor? Explain it to me? Why didn’t I tell them what I was really feeling?

Separation and Abandonment

After the marriage separation their mother is interested for a while in community living, subjecting the children to another experiment, and later still sinks into a deep depression that affects them all.

Finally, in a burst of desperate willpower, she decided to exile herself. Hers was not political, but an exile of love. The pretext was getting a doctorate in urban and regional planning in the south of France.

But before they were sent to France, there was a period where their maternal grandmother – who much favoured her brother- came to live with and look after them. Full of questions about why their parents left them in this situation, the grandmother gave her usual cryptic response:

‘Since when do ducks shoot rifles?’ she’d say, meaning that children should not demand accountability from adults.

Heightened Observations, Humorous Occasions

Part II narrates the period with grandmother in charge, made all the more challenging for being in their own home, one that had held so many previously fond memories.

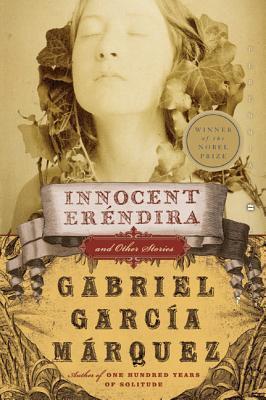

Reading was frowned upon, but the discovery of Gabriel Marcia Marquez’s The Incredible and Sad Tale of Innocent Erendira and her Heartless Grandmother cheered her up and provided a kind of solace.

Doctor, this discovery, as exaggerated as it sounds, was like meeting a guardian angel, or at least a friend I could trust, which was, in those days, equally unlikely. The book understood me better than anyone else in the world and, if that was not enough, made it possible for me to speak about things that were hard to admit to myself, like the undeniable urge to kill someone in my family.

From Mexico City to Aix-en-Provence

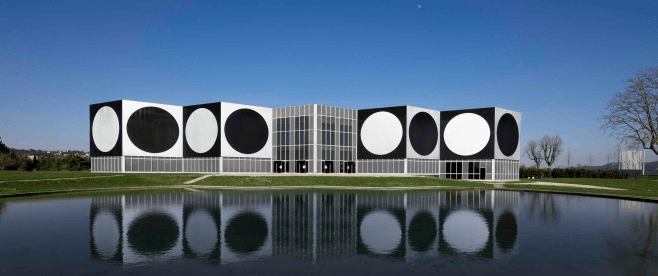

As I began part III, I was surprised to find the two young children following their mother to the south of France, to the Jas de Bouffan quartier of Aix en Provence near the musée Vasarely.

If I was already engaged in the novel, now I was riveted. I know the quartier well and the schools she and her brother are sent to, it awakened my own memories of being an outsider at the school gate, waiting for children to exit from the well regulated school environment.

I have no doubt that my mother sought in Aix the institution that most resembled our school in Mexico. The percentage of atypical beings was equal, or maybe even higher. But still… everything there seemed strange to me.

From From the public Freinet education at La Mareschalé to the local middle school, Collège au Jas de Bouffan, a mix of children from multiple origins, North African, Indian, Asian, Caribbean and French.

To survive in this climate, I had to adapt my vocabulary to the local argot – a mix of Arabic and Southern French – that was spoken around me, and my mannerisms to those of the lords of the cantine.

In Part IV there is a visit back to Mexico, before Part V where they are sent off to a the infamous French institution, the colonie de vacances; supervised holiday camps organised according to interests or specialities, full of young people employed as ‘camp animateurs‘ an idealised form of first employment, being paid to be on holiday, looking after tweens and emerging teens.

The French experience is so well depicted, and gives an insight into the child’s perspective of being an uncommon foreigner among a population of more common second or third generation immigrants. When it ends back in Mexico City, I find myself wishing there were a follow up novel, to find out more about a life that started in this unusual way and had all these experiences in their formative years.

The novel is so engaging, a fascinating insight into a life that delves beneath the surface of events and happenings in a family that is culturally fascinating, as it moves between Mexico City and Aix en Provence, traversing childhood and adolescence, the relationships between a girl, her peers at different ages, her parents and her grandmother.

And then there are the layers of literary references, including the reference to the title, but those I leave the prospective reader to discover for themselves.

I loved it! Highly Recommended.

Author, Guadalupe Nettel

Guadalupe Nettel (born 1973) is a Mexican writer. She was born in Mexico City and obtained a PhD in linguistics from the École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales in Paris. She has published in several genres, both fiction and non-fiction.

The New York Times described Nettel’s acclaimed English-language debut, Natural Histories as “five flawless stories”. A Bogota 39 author and Granta “Best Untranslated Writer” The Body Where I Was Born was her first novel to appear in English. Her work has since been translated into more than twenty languages and adapted for theatre and film. Still Born, her most recent novel, was shortlisted for the 2023 International Booker Prize and her latest collection of short stories The Accidentals tr. Rosalind Harvey was published in April 2025.

She has edited cultural and literary magazines such as Número Cero and Revista de la Universidad de México. She lives in Paris as a writer in residence at the Columbia University Institute for Ideas and Imagination.

Later, Laura, to ensure pregnancy doesn’t occur accidentally, takes the drastic measure of having her tubes tied, forever removing that risk.

Later, Laura, to ensure pregnancy doesn’t occur accidentally, takes the drastic measure of having her tubes tied, forever removing that risk.

Meanwhile, outside Laura’s apartment a pair of pigeons with two eggs in their nest (a refuge she tried to destroy without success), appear to have been subject to a brood parasite.

Meanwhile, outside Laura’s apartment a pair of pigeons with two eggs in their nest (a refuge she tried to destroy without success), appear to have been subject to a brood parasite.

A divorced woman, Nora Garcia (a cellist), returns for her deceased ex-husband Juan’s, (a pianist and composer) funeral; back to a Mexican village from her past, through the art and music they played and navigated together.

A divorced woman, Nora Garcia (a cellist), returns for her deceased ex-husband Juan’s, (a pianist and composer) funeral; back to a Mexican village from her past, through the art and music they played and navigated together. The novel is set in the present, on the afternoon that the body is displayed in the coffin in a room, and our narrator is a guest like many others, who aren’t sure to whom, they ought to offer condolences. She overhears snippets of conversations, adding to the cacophony of her own reflections.

The novel is set in the present, on the afternoon that the body is displayed in the coffin in a room, and our narrator is a guest like many others, who aren’t sure to whom, they ought to offer condolences. She overhears snippets of conversations, adding to the cacophony of her own reflections.

A prolific essayist, she is best known for her 1987 autobiography Las genealogías (The Family Tree), which blended her experiences of growing up Jewish in Catholic Mexico with her parents’ immigrant experiences. She also wrote fiction and nonfiction that shed new light on the seventeenth-century nun Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz. Among her many honors, she won the Magda Donato Prize for Las genealogías and received a Rockefeller Grant (1996) and a Guggenheim Fellowship (1998).

A prolific essayist, she is best known for her 1987 autobiography Las genealogías (The Family Tree), which blended her experiences of growing up Jewish in Catholic Mexico with her parents’ immigrant experiences. She also wrote fiction and nonfiction that shed new light on the seventeenth-century nun Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz. Among her many honors, she won the Magda Donato Prize for Las genealogías and received a Rockefeller Grant (1996) and a Guggenheim Fellowship (1998). I picked up Loop for WIT (Women in Translation) month and I loved it. I had few expectations going into reading it and was delightfully surprised by how much I enjoyed its unique, meandering, playful style.

I picked up Loop for WIT (Women in Translation) month and I loved it. I had few expectations going into reading it and was delightfully surprised by how much I enjoyed its unique, meandering, playful style. The narrator is waiting for the return of her boyfriend, who has travelled to Spain after the death of his mother.

The narrator is waiting for the return of her boyfriend, who has travelled to Spain after the death of his mother. A celebration of the yin aspect of life, the jewel within. And that jewel of a song, sung by both

A celebration of the yin aspect of life, the jewel within. And that jewel of a song, sung by both  Brenda Lozano is a novelist, essayist and editor. She was born in Mexico in 1981.

Brenda Lozano is a novelist, essayist and editor. She was born in Mexico in 1981.