It seems a strange title for a book, until we understand it is a memoir of adoption, of secrecy, of a love denied, forbidden. And the woman writing it, comes to realise, how very similar the continued secrecy surrounding spending time with her birth mother is, to conducting an illicit affair. So she calls it that. It’s like an unwritten 13th commandment: Thou shalt not have any relation whatsoever with thy illegitimate child.

It’s set in Ireland, a country reluctant to let go of old ways, still in throe to a traditional family culture that shamed, blamed and punished young women for being the life-bearers they are – insisting they follow a code of moral behaviour documented by a system of domination, upheld by the church, supported by the state – a system that bore no consequence on men – young or old – who were equally responsible for the predicament of women.

It’s set in Ireland, a country reluctant to let go of old ways, still in throe to a traditional family culture that shamed, blamed and punished young women for being the life-bearers they are – insisting they follow a code of moral behaviour documented by a system of domination, upheld by the church, supported by the state – a system that bore no consequence on men – young or old – who were equally responsible for the predicament of women.

“If there is anger in this book it is anger at the profound and despicable sexual double standard in Ireland. Men walked away without ever having to confront their role in these relationships.”

Eventually women in Ireland were given access to a means of preventing unwanted pregnancy, though not until Feb 20, 1985 when the Irish government defied the powerful Catholic Church, seen until this day as lacking compassion, in approving the sale of contraception, and more recently in a 2018 referendum, repealing its abortion ban (outlawed in 1861 with possible life imprisonment), acknowledged as a dramatic reversal of the Catholic church’s domination of Irish society.

For years, Ireland created and implemented what is referred to as an architecture of containment, institutions such as the Magdalen laundries (also referred to as asylums) removed morally questionable women from their homes (young women who became pregnant outside of marriage, or whose male family members complained about their behavior). They removed their children if they were pregnant then put them to work, washing ‘the nation’s dirty laundry’, thanks to lucrative state contracts provided to the institutions to fulfill. The last Magdalene laundries closed in Dublin in 1996 and the truth of what happened to those unmarried mothers continues to be investigated through the CLANN project.

For years, Ireland created and implemented what is referred to as an architecture of containment, institutions such as the Magdalen laundries (also referred to as asylums) removed morally questionable women from their homes (young women who became pregnant outside of marriage, or whose male family members complained about their behavior). They removed their children if they were pregnant then put them to work, washing ‘the nation’s dirty laundry’, thanks to lucrative state contracts provided to the institutions to fulfill. The last Magdalene laundries closed in Dublin in 1996 and the truth of what happened to those unmarried mothers continues to be investigated through the CLANN project.

Book Review

Caitriona Palmer was born in Dublin, raised in a caring family with two children of their own, the parents adopting after a miscarriage and recommendation Mary (the mother) should have a hysterectomy. If they wanted another child, adoption would be the only path.

She had a happy childhood and grew up in a very happy home, defiantly happy in fact, she would tell people early on she was adopted, almost proud of it she said, in her mind it had had no impact on her life, it didn’t change her or make her who she was, however she was constantly shadowed by a consistent ache, something she refused to confront or admit had anything to do with being separated from her biological mother at birth.

The book opens as Caitriona is about to meet her birth mother Sarah (not her real name) for the first time, a highly anticipated event, and yet as it unfolds, and she hears someone walk up the steps, about to fulfill a desire she has initiated, she becomes filled with dread and as the woman rushes towards her, repeating her name:

I said nothing. I felt nothing.

‘I’ll leave you both to it then,’ I heard Catherine say.

‘Don’t go’, I wanted to scream at her. ‘Please don’t go. Stay. Stay here with me, please. Don’t leave me alone with this woman.’

It is the beginning of the many conflicted feelings she will encounter within herself as that aspect of herself she was born into awakens as an emotional itch deep inside her she can neither locate or explain, at a time in her life when outwardly, living life as the person she was raised to be, she couldn’t have been happier. She was 26 years old, working in a dream job for Physicians for Human Rights in the US, in love and happy. She put her anxiety down to problems with her expiring student visa, though when her employer found a solution by transferring her to Bosnia, it didn’t heal the anxiety, if anything it made it worse.

There, a small team of forensic scientists was overseeing the exhumation of hundreds of mass graves left after the war and attempting to determine the fate of over 7,500 missing men and boys from the UN safe haven of Srebrenica, which had been overrun by Serb forces four years earlier.

After a day when she and a small team broke into an abandoned hospital in search of records, the source of her own anxiety presented itself to her.

In that moment, filling our arms with the dusty paperwork, I felt a sliver of illumination. Driving back to Tuzla later that afternoon, our pilfered medical dossiers on our laps, the mood in the car jovial, I returned again to that moment, massaging the memory, trying to knead to the surface the revelation lurking beneath. What was I doing helping to search for the files of dead strangers when it was plainly obvious that I needed to search for own?

Though there could be no comparison between her loss and that of these families, it was this extreme situation that revealed her own source of anxiety and set her on a path to do something she had denied she would ever do.

She embarks on her search and despite the difficulties many encounter in Ireland, where Irish adoptees have no automatic right to access their adoption files, birth certificate, health, heritage or history information she manages to access information about her birth relatively easily. The agency traces her birth mother and facilitates that first and many subsequent meetings.

Despite the initial shock, they develop a close relationship, but with one significant and ultimately destructive condition, that she remain a secret, for her birth mother continued to harbour great shame and was terrified of the impact this knowledge might have on her current life.

By the close of that year, I had come to detest the power imbalance in our relationship, seeing myself as the cause of Sarah’s shame and paranoia, her sadness and regret. I hated being invisible to her husband, evidently a good man who adored her, and to her three children, half-siblings that I longed to meet.

Palmer digs deep into the history of adoption in Ireland, armed with journalistic skills (now a freelance journalist in Washington DC) she researches archives and interviews her parents and birth mother as if subjects of a news story, to get to the heart of this institution that wrenched families apart and caused such fear and trauma in young Irish women, leaving emotional scars many of them would have all their lives.

Feminism might have been on the march, but the women in Sarah’s world … had conspired to punish her for stepping out of line. ‘If you want to get people to behave, show what happens to those who don’t,’ an Irish historian once said to me about Ireland’s culture of female surveillance and the institutionalization of unmarried mothers. ‘Make them feel part of that punishment.’ Her Aunt’s verdict – “Nobody will ever look at you again. You’re finished.” – echoed constantly in Sarah’s mind.

One couple she researched, were married with more children, but didn’t want to know the child they had parented and given away before marriage.

“What is that? How can this legacy of shame even prevent a couple from accepting their own biological child? Why can they not open the door?

“This book was meant to answer that. But I don’t know why Ireland has let so many people down. I was meant to grow up and be grateful and never want to look at my past. Because things worked out well; I was given a wonderful family and have done well; that’s meant to be enough.”

For an adoptee or a birth mother, it’s both insightful and an extremely painful read, especially given the author’s own awakening from that happy dreamy childhood and early adult life that held no place for her unknown genetic history, or for any other familial bond or connection. She couldn’t recognise what she hadn’t known or experienced and because her adoption was something known, it seemed as if this life could be lived without consequence. In a recent interview post publication, Palmer describes this:

What I didn’t understand was that that primary loss impacted me, it did change me, I’m still grieving her. Despite my wonderful happy life, amazing husband and children… I’m internally grieving, this woman, this ghost, that’s a love that I’ll never regain in a way, memoir is an attempt to grasp at that.

I wanted people to know you can grow up happily adopted and still have this hole, I always feel like there is a hole deep down inside of me that I can’t quite fill, in spite of the abundance of love that surrounds me, this primary loss is profound.

It’s a story that doesn’t end on the last page, and will leave readers like me, curious to know what impact this book had on the relationship. The podcast below, brings us up to date with where things are at since the book was published, including mention of the hundreds of letters that Caitriona has received, the many people who have had similar experiences, heartened to learn that their experience brought solace to some, in their ability to share with her their stories.

Asked, given what has transpired, would she still do what she did, she responds:

I would have done the same, as it was approached ethically and with love – but I wouldn’t allow it to remain a secret so long, the weight of a secret… every human being wants this sense of belonging and yet we are expected to express gratitude and get along, we are a part of each of those things and that’s a beautiful thing…

The big gap in all this, and for this entire process, is the lack of facility for healing, for giving adoptive parents, birth parents and the children affected by adoption, resources to help them understand what they might go through and if they do, how to manage that, how to heal from that, live with that, recognise the characteristics that come with having lived though such trauma.

The world we live in today is a long way from being accomplished at providing that, and some countries are no doubt better than others, hopefully it is coming, it doesn’t take too much digging if one can find tools of well-being that might bring about individual change and healing.

Further Reading/Listening

Caitríona – I’m Still Grieving Her – Podcast – on building a relationship with her birth mother, the heartbreak of being kept a secret and the high cost she’s paid for sharing her story

The State has a duty to tell adoptees the truth Caitríona Palmer: Shadowy adoption system is the last obstacle to a modern Ireland – June 2018

CLANN: IRELAND’S UNMARRIED MOTHERS AND THEIR CHILDREN – establishing the truth of what happened to unmarried mothers and their children in 20th century Ireland, providing free legal assistance

The concept of this illustrated children’s book really appealed to me. It’s inspired and based on the childhood of the Swedish artist Berta Hansson (1910-1994) during the period in her life when she was 12 years old and wanted to be outdoors in nature or painting or making birds out of clay.

The concept of this illustrated children’s book really appealed to me. It’s inspired and based on the childhood of the Swedish artist Berta Hansson (1910-1994) during the period in her life when she was 12 years old and wanted to be outdoors in nature or painting or making birds out of clay.

I received a few messages from friends and family in New Zealand wishing me a Happy Mother’s Day, which was lovely and unexpected.

I received a few messages from friends and family in New Zealand wishing me a Happy Mother’s Day, which was lovely and unexpected.

In the first of so many I still owe thank you’s to, I would like to say a heart-felt public thank you to a woman who makes magic with words, author

In the first of so many I still owe thank you’s to, I would like to say a heart-felt public thank you to a woman who makes magic with words, author

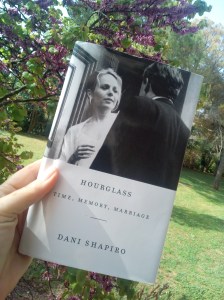

I’ve not read any of Dani Shapiro’s previous works, this short book was passed to me by a friend and read in an afternoon. I enjoyed reading it, though I couldn’t say I related to it. It’s a very personal observation of a marriage, of the passage of time, a woman observing herself change, reflecting on her inclinations and trying to understand herself, her husband and their evolving relationship. As the title indicates, it’s a reflection on time passing, on memory and on marriage.

It’s full of nostalgia for moments passed, brought back to life as she picks up journals from girlhood and her earlier life and quotes from them, in particular, from her honeymoon spent in France. She wonders about the woman she was then.

She worries about the lack of a plan, despite being in her fifties and her husband almost sixty. She shares these anxious moments, as she begins to lose a little faith in the words her husband has uttered in the past, words that gave her reassurance “I’ll take care of it”.

Anyone who has lived with that kind of comfort will likely relate, but inherent within it lies a deep vulnerability, a fissure, a unassuageable fear of loss. It is here her words pierce the fabric of living, when they illuminate the cracks in the facade, opening a small window into that anxiety-inducing perception of reality that sees itself as separate.

It is that undercurrent of misplaced fear that disconcerts me, for there is no hint of resolution, little evidence of a desire to go within and face the abyss, to heal it. She remains focused on that which is external and therein perhaps lies the problem. Maybe that is a memoir still to come, when she will embark on the inner journey and learn to listen to her own guidance, to the whispers of her soul that are capable of reassuring her more than anyone or anything on the outside. Something that marriage appears to protect us from, at least until menopause, a subject she doesn’t mention but one that can also unravel our perceptions of the life structures we’ve created in our minds.

I’ve not read any of Dani Shapiro’s previous works, this short book was passed to me by a friend and read in an afternoon. I enjoyed reading it, though I couldn’t say I related to it. It’s a very personal observation of a marriage, of the passage of time, a woman observing herself change, reflecting on her inclinations and trying to understand herself, her husband and their evolving relationship. As the title indicates, it’s a reflection on time passing, on memory and on marriage.

It’s full of nostalgia for moments passed, brought back to life as she picks up journals from girlhood and her earlier life and quotes from them, in particular, from her honeymoon spent in France. She wonders about the woman she was then.

She worries about the lack of a plan, despite being in her fifties and her husband almost sixty. She shares these anxious moments, as she begins to lose a little faith in the words her husband has uttered in the past, words that gave her reassurance “I’ll take care of it”.

Anyone who has lived with that kind of comfort will likely relate, but inherent within it lies a deep vulnerability, a fissure, a unassuageable fear of loss. It is here her words pierce the fabric of living, when they illuminate the cracks in the facade, opening a small window into that anxiety-inducing perception of reality that sees itself as separate.

It is that undercurrent of misplaced fear that disconcerts me, for there is no hint of resolution, little evidence of a desire to go within and face the abyss, to heal it. She remains focused on that which is external and therein perhaps lies the problem. Maybe that is a memoir still to come, when she will embark on the inner journey and learn to listen to her own guidance, to the whispers of her soul that are capable of reassuring her more than anyone or anything on the outside. Something that marriage appears to protect us from, at least until menopause, a subject she doesn’t mention but one that can also unravel our perceptions of the life structures we’ve created in our minds.

It’s set in Ireland, a country reluctant to let go of old ways, still in throe to a traditional family culture that shamed, blamed and punished young women for being the life-bearers they are – insisting they follow a code of moral behaviour documented by a system of domination, upheld by the church, supported by the state – a system that bore no consequence on men – young or old – who were equally responsible for the predicament of women.

It’s set in Ireland, a country reluctant to let go of old ways, still in throe to a traditional family culture that shamed, blamed and punished young women for being the life-bearers they are – insisting they follow a code of moral behaviour documented by a system of domination, upheld by the church, supported by the state – a system that bore no consequence on men – young or old – who were equally responsible for the predicament of women.

Louise Beech is a unique author who I feel like I have a personal connection with, after the incredible experience of reading her debut novel How To Be Brave in October 2016, which for me included communicating with her as I endured a hellish experience on the 9th floor of Timone Hospital in Marseille. Twitter hashtags truly can bring incredible people into your lives at pivotal moments, both the living and those that have passed on. #LouiseBeech

Louise Beech is a unique author who I feel like I have a personal connection with, after the incredible experience of reading her debut novel How To Be Brave in October 2016, which for me included communicating with her as I endured a hellish experience on the 9th floor of Timone Hospital in Marseille. Twitter hashtags truly can bring incredible people into your lives at pivotal moments, both the living and those that have passed on. #LouiseBeech It was also the story of her grandfather who had been lost at sea for over 50 days when he was a young man. Both the diagnosis and the story of the grandfather are true stories, however she used her creativity and imagination to write a novel that blends fact and fiction, taking the reader on an emotionally charged, high sea journey towards healing.

It was also the story of her grandfather who had been lost at sea for over 50 days when he was a young man. Both the diagnosis and the story of the grandfather are true stories, however she used her creativity and imagination to write a novel that blends fact and fiction, taking the reader on an emotionally charged, high sea journey towards healing. In chapter two a woman named Bernadette tells us that the book is missing. It is the day she has finally summoned the courage to leave her husband, she’s spent all day preparing and fretting about it, he is a man who values impeccable timing, expecting others to meet his standards, especially his wife Bernadette. She is waiting for him to walk through the door at 6pm like he does every evening before she intends to leave. Only he is late, more than late, he doesn’t come home at all.

In chapter two a woman named Bernadette tells us that the book is missing. It is the day she has finally summoned the courage to leave her husband, she’s spent all day preparing and fretting about it, he is a man who values impeccable timing, expecting others to meet his standards, especially his wife Bernadette. She is waiting for him to walk through the door at 6pm like he does every evening before she intends to leave. Only he is late, more than late, he doesn’t come home at all.

That transition she made and the mentoring she received became the subject of her first book

That transition she made and the mentoring she received became the subject of her first book  In Worthy, Boost Your Self-Worth to Grow Your Net Worth, she takes the jump a step further and analyses what might be behind the reluctance, or resistance as she likes to call it, to change. She tells the story behind the story of her own life, of how she rarely spent money on herself, but often on her husband because she was trying to make him happy. Through coaching, she was able to have greater awareness of her own patterns and see how she was getting in her own way of achieving what she wanted.

In Worthy, Boost Your Self-Worth to Grow Your Net Worth, she takes the jump a step further and analyses what might be behind the reluctance, or resistance as she likes to call it, to change. She tells the story behind the story of her own life, of how she rarely spent money on herself, but often on her husband because she was trying to make him happy. Through coaching, she was able to have greater awareness of her own patterns and see how she was getting in her own way of achieving what she wanted. The book moves further on, into defining what you want most and how to move from excuses to action, to taking back your power, taking responsibility, practising self-trust and self-respect.

The book moves further on, into defining what you want most and how to move from excuses to action, to taking back your power, taking responsibility, practising self-trust and self-respect.