I haven’t read much Japanese literature so when I saw Mieko Kawakami’s novel Breasts and Eggs at a booksale I picked it up, recalling it had caused much interest among readers at the time of its translation into English. It caused a significant reaction in Japan when originally published, a bestseller spurned by traditionalists.

It was a New York Times Notable Book of the Year and one of TIME’s Best 10 Books of 2020 and established the author as something of a feminist icon, exploring the inner lives of women through the ages.

A Woman’s Lot

Breasts and Eggs is set in two time periods eight years apart and centres around 30 year old woman Natsuko, a writer living in Tokyo and those two themes, Breasts and Eggs; or Appearance and Mothering.

I’m still in the same apartment with the slanted, peeling walls and the same overbearing afternoon sun, surviving off the same minimum wage job, working full time for not a whole lot more than 100,000 yen a month, and still writing and writing, with no idea whether it’s ever going to get me anywhere. My life was like a dusty shelf in an old book store, where every volume was exactly where it had been for ages, the only discernable change being that my body has aged another ten years.

Silence Speaks Volumes

In the first part of the book her sister Makiko comes to visit with her 12 year old daughter Midoriko, who has stopped speaking to her mother. She writes her responses, we read her perspective through a few journal entries, which has become the place where she has conversations she is missing elsewhere.

Unspoken Job Requirements

Makiko is an ageing hostess whose occupation demands certain expectations of looks and she has become obsessed with breast augmentation surgery to the neglect of all else. It has been the topic of conversation with her sister for the last three months. Natsuko realises she doesn’t want her advice, just a sounding board. Their mother died when the girls were teenagers from breast cancer.

…after all these years, at thirty-nine, she still works at a bar five nights a week, living pretty much the same life as our mum. Another single mother, working herself to death.

While her sister goes for a consultation Natsuko spends time with her niece and ponders women’s bodies, pains, expectations, grievances, self-judgments, societal judgments, obsessions. During the visit, the three women confront their issues, desires and frustrations, building to resolution.

When Time Is Running Out and All is On the Table

In Part Two, eight years have passed and now it is Natsuko who arrives at an age of obsession, only her focus is on eggs, or the desire to have a child and the dilemma of not being in a relationship when the age of becoming eggless is in sight.

A Making Children Medical Procedure

She begins to research alternative ways of conceiving, finding ways to learn more and to meet people she might be able to discuss her desire. In doing so she discovers there is more to the subject than just a woman’s desire, there are moral considerations she hasn’t considered, that might affect her decision.

“Neither the medical community, not the parents who undergo this type of treatment, have adequately considered how the children – and this is about the children – will eventually see themselves,” Aizawa said, in summary. “As for donors, most of them haven’t given much thought to these issues, either. For them, it’s something akin to giving blood. Legal reform has a long, long way to go, but recent attention to the child’s right to know had led more and more hospitals to suspend treatment entirely…”

The Child Who Grows Up Not Knowing Shares As an Adult

Her interest leads her to new connections that increase the depth of her understanding and options available to her. By the time she makes her decision, she will be significantly more informed and understand the situation from multiple perspectives.

I thought about what I had said, but couldn’t explain what I meant. What made me want to know this person? What did I think it meant to have me as a mother? Who, or what, exactly, was I expecting? I knew I wasn’t making any sense, but I was doing all I could to string the words together and convey that meeting this person, whoever they may wind up being, was absolutely crucial to me.

It is an interesting, thought-provoking look at the lives of women trying to find fulfillment while navigating the challenges of single motherhood, health, womanhood, reproductive rights and familial relationships in non-nuclear families.

Further Reading

Article: Mieko Kawakami’s books: a complete guide, Naomi Frisby on literary sensation Mieko Kawakami Nov 2024

Guardian Interview: Mieko Kawakami: ‘Women are no longer content to shut up’ David McNeil, 18 Aug 2020

“I try to write from the child’s perspective – how they see the world,” says Kawakami. “Coming to the realisation that you’re alive is such a shock. One day, we’re thrown into life with no warning. And at some point, every one of us will die. It’s very hard to comprehend.”

Author, Mieko Kawakami

Born in Osaka, Japan Kawakami made her literary debut as a poet in 2006 and in 2007 published her first novella My Ego, My Teeth, And the World. Heaven, translated by Sam Bett and David Boyd, was shortlisted for the 2022 International Booker Prize.

Known for their poetic qualities, their insights into the female body and their preoccupation with ethics and the modern society, her books have been translated into over twenty languages. Her most recent novel that has been translated into English is All the Lovers in the Night.

Kawakami’s literary awards include the Akutagawa Prize, the Tanizaki Prize, and the Murasaki Shikibu Prize. She lives in Tokyo, Japan.

36 year old Koko raises her 11 year old daughter Kayako alone, she works part time teaching piano, though the way she is obliged to teach it pains her. Since she bought her apartment (thanks to a partial inheritance) she has also become independent of her family, something her sister Shoko constantly criticizes her for.

36 year old Koko raises her 11 year old daughter Kayako alone, she works part time teaching piano, though the way she is obliged to teach it pains her. Since she bought her apartment (thanks to a partial inheritance) she has also become independent of her family, something her sister Shoko constantly criticizes her for.

Yuko Tsushima (1947-2016) was a prolific writer, known for her stories that centre on women striving for survival and dignity outside the confines of patriarchal expectations. Groundbreaking in content and style, Tsushima authored more than 35 novels, as well as numerous essays and short stories.

Yuko Tsushima (1947-2016) was a prolific writer, known for her stories that centre on women striving for survival and dignity outside the confines of patriarchal expectations. Groundbreaking in content and style, Tsushima authored more than 35 novels, as well as numerous essays and short stories. From an extraordinary writer and storyteller who defies categorisation, another tale that stretches and flexes the readers imagination, hauntingly written, leaving me to wonder just how she does it, a thought I had after reading her novel, or story collection

From an extraordinary writer and storyteller who defies categorisation, another tale that stretches and flexes the readers imagination, hauntingly written, leaving me to wonder just how she does it, a thought I had after reading her novel, or story collection  The novella introduces Salimah, who found herself a job in the supermarket after her husband left her and her two sons as soon as they arrived in this foreign country. She attends an English class for learners of a second language where she meets a Japanese woman named Echnida who brings her small baby to class, an older Italian woman Olive, a group of young Swedish ‘nymphs’ and her teacher. She makes observations about her classmates and her own life, as she learns the language that is her entry into this foreign place.

The novella introduces Salimah, who found herself a job in the supermarket after her husband left her and her two sons as soon as they arrived in this foreign country. She attends an English class for learners of a second language where she meets a Japanese woman named Echnida who brings her small baby to class, an older Italian woman Olive, a group of young Swedish ‘nymphs’ and her teacher. She makes observations about her classmates and her own life, as she learns the language that is her entry into this foreign place. As time passes, new developments replace old situations, opportunities arise, Salimah’s son begins to be invited to play with a school friend, a pregnancy brings the three women together and it is as if they begin to create a community or family between them.

As time passes, new developments replace old situations, opportunities arise, Salimah’s son begins to be invited to play with a school friend, a pregnancy brings the three women together and it is as if they begin to create a community or family between them. I absolutely loved it and was reminded a little of my the experience of sitting in the French language class for immigrants, next to women from Russia, Uzbekistan, Cuba and Vietnam, women with whom it was only possible to converse in our limited French, supported by a teacher who spoke French (or Italian). So many stories, so many challenges each woman had to overcome to contend with life here, most of it unknown to any other, worn on their faces, mysteries the local population were unconcerned with.

I absolutely loved it and was reminded a little of my the experience of sitting in the French language class for immigrants, next to women from Russia, Uzbekistan, Cuba and Vietnam, women with whom it was only possible to converse in our limited French, supported by a teacher who spoke French (or Italian). So many stories, so many challenges each woman had to overcome to contend with life here, most of it unknown to any other, worn on their faces, mysteries the local population were unconcerned with. Iwaki Kei was born in Osaka. After graduating from college, she went to Australia to study English and ended up staying on, working as a Japanese tutor, an office clerk, and a translator. The country has now been her home for 20 years. Farewell, My Orange, her debut novel, won both the Dazai Osamu Prize (a Japanese literary award awarded annually to an outstanding, previously unpublished short story by an unrecognized author) and the

Iwaki Kei was born in Osaka. After graduating from college, she went to Australia to study English and ended up staying on, working as a Japanese tutor, an office clerk, and a translator. The country has now been her home for 20 years. Farewell, My Orange, her debut novel, won both the Dazai Osamu Prize (a Japanese literary award awarded annually to an outstanding, previously unpublished short story by an unrecognized author) and the  A mysterious novella that begins in a quiet humble way as we meet the young widow Yasuko whose husband, the only son of Meiko Togano, we learn died tragically in an avalanche.

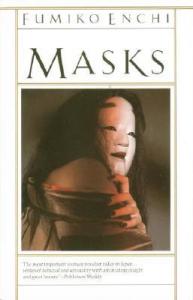

A mysterious novella that begins in a quiet humble way as we meet the young widow Yasuko whose husband, the only son of Meiko Togano, we learn died tragically in an avalanche. It is worth knowing a little about the plot of The Tale of Genji and the ‘Masks of Noh’ from the dramatic plays, as we realise there are likely to be references and connections to what is unfolding here. And not surprising given Fumiko Enchi translated this 1,000+ page novel into modern Japanese.

It is worth knowing a little about the plot of The Tale of Genji and the ‘Masks of Noh’ from the dramatic plays, as we realise there are likely to be references and connections to what is unfolding here. And not surprising given Fumiko Enchi translated this 1,000+ page novel into modern Japanese. Fumiko Enchi was a Tokyo born novelist and playright, the daughter of a distinguished philologist and linguist. Poorly as a child, she was home-schooled in English, French and Chinese literature by private tutors.

Fumiko Enchi was a Tokyo born novelist and playright, the daughter of a distinguished philologist and linguist. Poorly as a child, she was home-schooled in English, French and Chinese literature by private tutors.