An excellent Sunday afternoon read and pertinent to much that is being written and read in the media under the banner of the silencing of women today.

This short, articulate novella is a conversation, in the form of a lengthy letter from a widow to her best friend, whom she hasn’t seen for some years, but who is arriving tomorrow. It is set in Senegal, was originally written and published in French in 1980 and in English in 1981, the year in which the author died tragically of a long illness.

This short, articulate novella is a conversation, in the form of a lengthy letter from a widow to her best friend, whom she hasn’t seen for some years, but who is arriving tomorrow. It is set in Senegal, was originally written and published in French in 1980 and in English in 1981, the year in which the author died tragically of a long illness.

Our recent widow is reflecting on the emotional fallout of her husband’s death, how she is unable to detach from memories of better times in the past, during those 25 years where she was happily married and the only wife of her husband, thoughts interrupted by the more bitter, heart-breaking recent years where she was abandoned by him for the best friend of her daughter, a young woman, who traded the magic of youth for the allure of shiny things (with the exception of his silver-grey streaks, which he in turn trades in for the black dye of those in denial of the ageing process).

With his death, she must sit beside this young wife, have her inside her home for the funeral, in accordance with tradition. She is irritated by this necessity.

Was it madness, weakness, irresistible love? What inner confusion led Modou Fall to marry Binetou?

To overcome my bitterness, I think of human destiny. Each life has its share of heroism, an obscure heroism, born of abdication, of renunciation and acceptance under the merciless whip of fate.

By turn she expresses shock, outrage, anger, resentment, pity until her thoughts turn with compassion towards those she must continue to aid, her children; to those who have supported her, her friends; including this endearing one about to arrive; she thinks too of the burden of responsibility of all women.

And to think that I loved this man passionately, to think that I gave him thirty years of my life, to think that twelve times over I carried his child. The addition of a rival to my life was not enough for him. In loving someone else, he burned his past, both morally and materially. He dared to commit such an act of disavowal.

And yet, what didn’t he do to make me his wife!

It is a lament, a paradox of feelings, a resentment of tradition, a wonder at those like her more liberated and courageous friend, who in protest at her own unfair treatment (a disapproving mother-in-law interferes – reminding me of Ayòbámi Adébáyò’s Stay with Me), took the road less travelled, taking her four sons, arming herself with renewed higher education and an enviable career abroad.

It is a lament, a paradox of feelings, a resentment of tradition, a wonder at those like her more liberated and courageous friend, who in protest at her own unfair treatment (a disapproving mother-in-law interferes – reminding me of Ayòbámi Adébáyò’s Stay with Me), took the road less travelled, taking her four sons, arming herself with renewed higher education and an enviable career abroad.

It is a testament to the plight of women everywhere, who live in sufferance to the old ways of patriarchy, whose articulate social conscience has little outlet except through their children, whose ability to contribute so much more is worn down by the age-old roles they continue to play, which render other qualities less effective when under utilised.

I am not indifferent to the irreversible currents of the women’s liberation that are lashing the world. This commotion that is shaking up every aspect of our lives reveals and illustrates our abilities.

My heart rejoices every time a woman emerges from the shadows. I know that the field of our gains is unstable, the retention of conquests difficult: social constraints are ever-present, and male egoism resists.

Instruments for some, baits for others, respected or despised, often muzzled, all women have almost the same fate, which religions or unjust legislation have sealed.

Ultimately, she posits, it is only love that can heal, that can engender peace and harmony and the success of family is born of the couple’s harmony, as the nation depends inevitably on the family.

I remain persuaded of the inevitable and necessary complementarity of man and woman.

Love, imperfect as it may be in its content and expression, remains the natural link between these two beings.

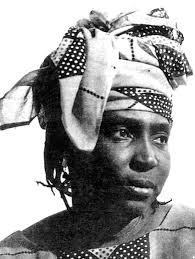

Mariama Bâ (April 17, 1929 – August 17, 1981) was a Senegalese author and feminist, who wrote in French. Born in Dakar to an educated and well-off family, her father was Minister of Health, her grandfather a translator in the occupying French regime. After the premature death of her mother, she was largely raised in the traditional manner by her maternal grandparents.

Mariama Bâ (April 17, 1929 – August 17, 1981) was a Senegalese author and feminist, who wrote in French. Born in Dakar to an educated and well-off family, her father was Minister of Health, her grandfather a translator in the occupying French regime. After the premature death of her mother, she was largely raised in the traditional manner by her maternal grandparents.

She was a novelist, teacher and feminist, active from 1979 to 1981 in Senegal, West Africa. Bâ’s source of determination and commitment to the feminist cause stemmed from her background, her parents’ life, her schooling and subsequent experiences as a wife, mother and friend.

Her contribution is considered important in modern African studies as she was among the first to illustrate the disadvantaged position of women in African society. She believed in her mission to expose and critique the rationalisations employed to justify established power structures. Bâ’s work focused on the grandmother, the mother, the sister, the daughter, the cousin and the friend, how they deserve the title “mother of Africa”, and how important they are for society.

It’s an excellent short read and an excellent account from the inside of a polygamous society, highlighting the important role women already have and the greater one they could embrace if men and women were to give greater respect to the couple, the family, or at least to exit it with greater respect than this model implies.

Once I got into the rhythm of this, which is to say, reading in French, and getting past the need to look up too many new words, I couldn’t put this down, by the time I found my reading rhythm, the lives of Gabriel (Gaby) and his sister Ana, his parents, his friends had their claws in me and I had to know what was going to happen next.

Once I got into the rhythm of this, which is to say, reading in French, and getting past the need to look up too many new words, I couldn’t put this down, by the time I found my reading rhythm, the lives of Gabriel (Gaby) and his sister Ana, his parents, his friends had their claws in me and I had to know what was going to happen next. His father is French, his mother Tutsi from Rwanda, they live in the small country bordering Rwanda, Tanzania and the Democratic Republic of Congo, called Burundi. It boasts the second deepest lake in the world, Lake Tanganyika, which occupies a large portion of the country’s border and is part of the African Great Lakes region.

His father is French, his mother Tutsi from Rwanda, they live in the small country bordering Rwanda, Tanzania and the Democratic Republic of Congo, called Burundi. It boasts the second deepest lake in the world, Lake Tanganyika, which occupies a large portion of the country’s border and is part of the African Great Lakes region.

The ending is not really an ending, it could be said there is more than one ending and perhaps there may even be another book. I found it incredibly moving and was amazed to be so moved in a language that is not my own. An incredible feat of writing, a wonderful talent.

The ending is not really an ending, it could be said there is more than one ending and perhaps there may even be another book. I found it incredibly moving and was amazed to be so moved in a language that is not my own. An incredible feat of writing, a wonderful talent. Nothing Holds Back the Night is the book Delphine de Vigan avoided writing until she could no longer resist its call. It is a book about her mother Lucile, who she introduces to us on the first page as she enters her apartment and discovers her sleeping, the long, cold, hard sleep of death. Her mother was 61-years-old.

Nothing Holds Back the Night is the book Delphine de Vigan avoided writing until she could no longer resist its call. It is a book about her mother Lucile, who she introduces to us on the first page as she enters her apartment and discovers her sleeping, the long, cold, hard sleep of death. Her mother was 61-years-old. I read this book in a day, it’s one of those narratives that once you start you want to continue reading, it’s described as autofiction, a kind of autobiography and fiction, though there is little doubt it is the story of the author’s mother, as she constructs thoughts and dialogue inspired by the information provided by family members, acknowledging that for many of the events, some often have a different memory which she even shares.

I read this book in a day, it’s one of those narratives that once you start you want to continue reading, it’s described as autofiction, a kind of autobiography and fiction, though there is little doubt it is the story of the author’s mother, as she constructs thoughts and dialogue inspired by the information provided by family members, acknowledging that for many of the events, some often have a different memory which she even shares. After her abrupt departure from Paris back to her father’s home in Montigny, to the village home where she grew up, I was curious to know what was to come of our troubled Claudine and her errant husband.

After her abrupt departure from Paris back to her father’s home in Montigny, to the village home where she grew up, I was curious to know what was to come of our troubled Claudine and her errant husband. However he is more than happy that she spend time with his sister Marthe, about whom he writes:

However he is more than happy that she spend time with his sister Marthe, about whom he writes:

I loved Claudine at School for her exuberant overconfidence and love of nature, Claudine in Paris for her naivety and prudence, realising there was much about life she had still to learn and Claudine Married for the melancholy of marriage, of the realisation of her false ideals and indulgence of strong emotional impulses.

I loved Claudine at School for her exuberant overconfidence and love of nature, Claudine in Paris for her naivety and prudence, realising there was much about life she had still to learn and Claudine Married for the melancholy of marriage, of the realisation of her false ideals and indulgence of strong emotional impulses. The impulsive Claudine, thinking a marriage of her own making and choice (not one chosen by her father or suggested by a man who had feelings for her that weren’t reciprocated) embarks on her marital journey which begins with fifteen months of a vagabond life, travelling to the annual opera Festival de Bayreuth, in Germany, to Switzerland and the south of France.

The impulsive Claudine, thinking a marriage of her own making and choice (not one chosen by her father or suggested by a man who had feelings for her that weren’t reciprocated) embarks on her marital journey which begins with fifteen months of a vagabond life, travelling to the annual opera Festival de Bayreuth, in Germany, to Switzerland and the south of France. Their relationship plays itself out, up to the denouement, when Claudine seeking refuge decides to return to Montigny, to the safety of her childhood home, the woods, her animals whose loyalty she is assured of, and the affection of the maid Mélie and her humble, absent-minded father.

Their relationship plays itself out, up to the denouement, when Claudine seeking refuge decides to return to Montigny, to the safety of her childhood home, the woods, her animals whose loyalty she is assured of, and the affection of the maid Mélie and her humble, absent-minded father. If Claudine at School represents the unfettered, exuberant joys of teenage freedom, of the innocent and immature love between friends and the cruel indulgences of playful spite, Claudine in Paris is the slap in the face of regarding an approaching adult, urban world, one where the streets are inhabited by hidden dangers, the skies are more gloomy, people are not what they seem, even old friends from school become unrecognisable when the city and her frustrated inhabitants get their clutch onto the innocent.

If Claudine at School represents the unfettered, exuberant joys of teenage freedom, of the innocent and immature love between friends and the cruel indulgences of playful spite, Claudine in Paris is the slap in the face of regarding an approaching adult, urban world, one where the streets are inhabited by hidden dangers, the skies are more gloomy, people are not what they seem, even old friends from school become unrecognisable when the city and her frustrated inhabitants get their clutch onto the innocent.

Below is a summary of

Below is a summary of  As The Story of the Cannibal Woman opens, we learn Rosélie is a 50-year-old recent widow, living alone, without family connections and few friends in Cape Town, South Africa, after the brutal murder of her white British husband, a retired university professor, who nipped out after midnight one evening, allegedly to buy cigarettes and never returned home.

As The Story of the Cannibal Woman opens, we learn Rosélie is a 50-year-old recent widow, living alone, without family connections and few friends in Cape Town, South Africa, after the brutal murder of her white British husband, a retired university professor, who nipped out after midnight one evening, allegedly to buy cigarettes and never returned home. At the same time Rosalie is going through her crisis, there is a well publicised case in the newspapers of a woman named Fiela, who allegedly murdered her husband. In court she refuses to speak, the public begin to turn against her, some calling her a witch, others a cannibal. The police officer on Stephen’s case wonders aloud whether she might open up to Rosalie, as many of her patients do. Rosalie has imaginary conversations with Fiela, the one personality to whom she feels able to ask questions (albeit in her dreams), that she can not utter to anyone else:

At the same time Rosalie is going through her crisis, there is a well publicised case in the newspapers of a woman named Fiela, who allegedly murdered her husband. In court she refuses to speak, the public begin to turn against her, some calling her a witch, others a cannibal. The police officer on Stephen’s case wonders aloud whether she might open up to Rosalie, as many of her patients do. Rosalie has imaginary conversations with Fiela, the one personality to whom she feels able to ask questions (albeit in her dreams), that she can not utter to anyone else:

Ladivine, written by the Senegalese-French writer Marie NDiaye, known for her 2009 Prix Goncourt award-winning Trois Femmes Puissantes (Three Strong Women) came to my attention when it was longlisted for the Man Booker International Prize in 2016.

Ladivine, written by the Senegalese-French writer Marie NDiaye, known for her 2009 Prix Goncourt award-winning Trois Femmes Puissantes (Three Strong Women) came to my attention when it was longlisted for the Man Booker International Prize in 2016.

“NDiaye’s novels frequently feature biracial couples, absent or distant fathers, and strained filial relationships. Her characters often feel ill at ease within their communities, and struggle with doubts that they are not who they believe or wish themselves to be.” New Republic, The Metamorphoses of Marie NDiaye by Jeffrey Zuckerman

“NDiaye’s novels frequently feature biracial couples, absent or distant fathers, and strained filial relationships. Her characters often feel ill at ease within their communities, and struggle with doubts that they are not who they believe or wish themselves to be.” New Republic, The Metamorphoses of Marie NDiaye by Jeffrey Zuckerman Rachel Cooke in this Guardian article

Rachel Cooke in this Guardian article

It should have been perfect, but things change when an old friend of her mother’s Anne arrives and she and her father announce their intention to marry. Although it is actually something Cecile feels is right for them and she adores Anne, part of her resents what signifies to her the end to the playful era she and her father have indulged, for Anne’s presence in their lives will certainly bring order and sensibility.

It should have been perfect, but things change when an old friend of her mother’s Anne arrives and she and her father announce their intention to marry. Although it is actually something Cecile feels is right for them and she adores Anne, part of her resents what signifies to her the end to the playful era she and her father have indulged, for Anne’s presence in their lives will certainly bring order and sensibility.