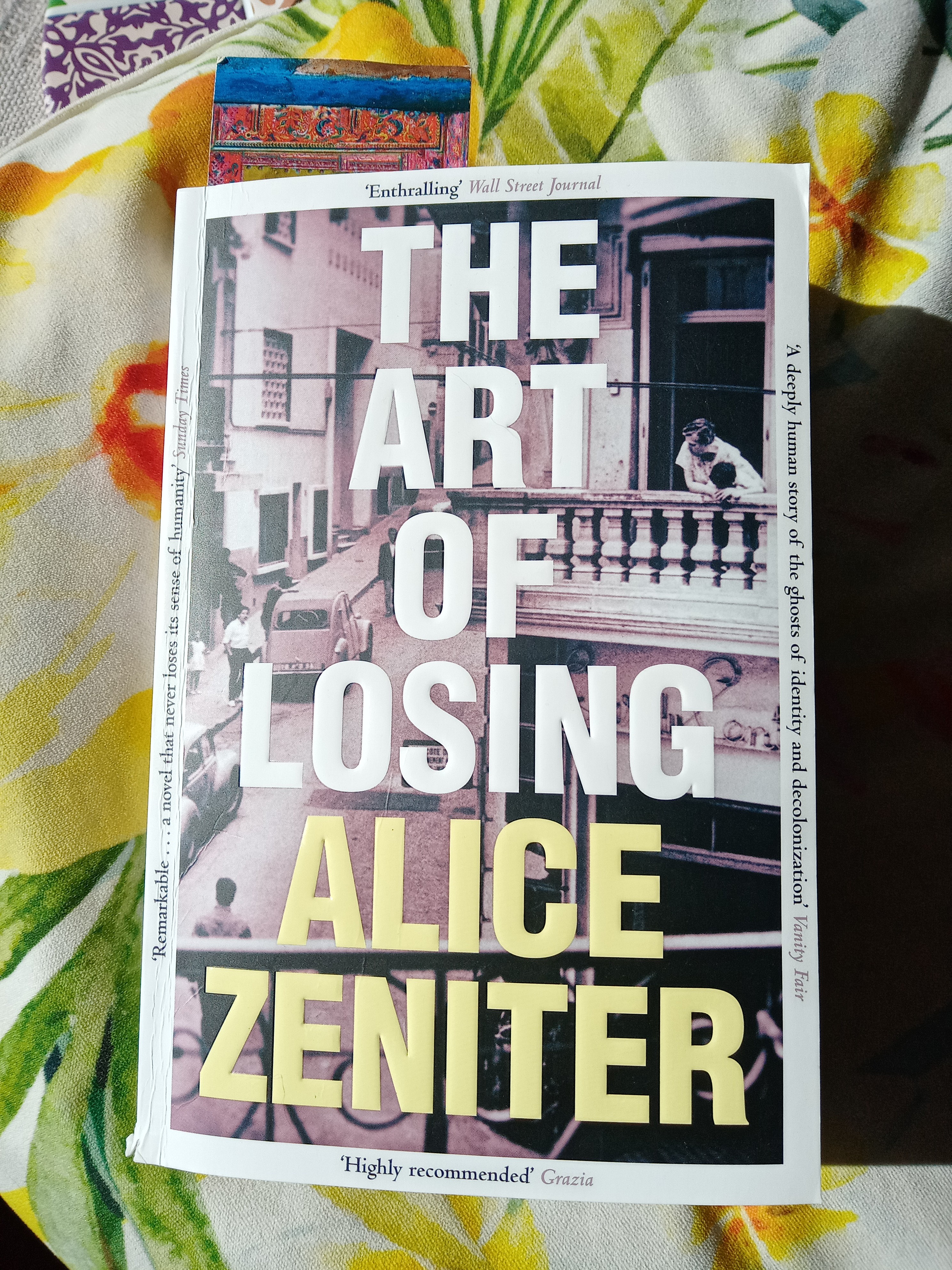

Most Popular Library Book of 2022

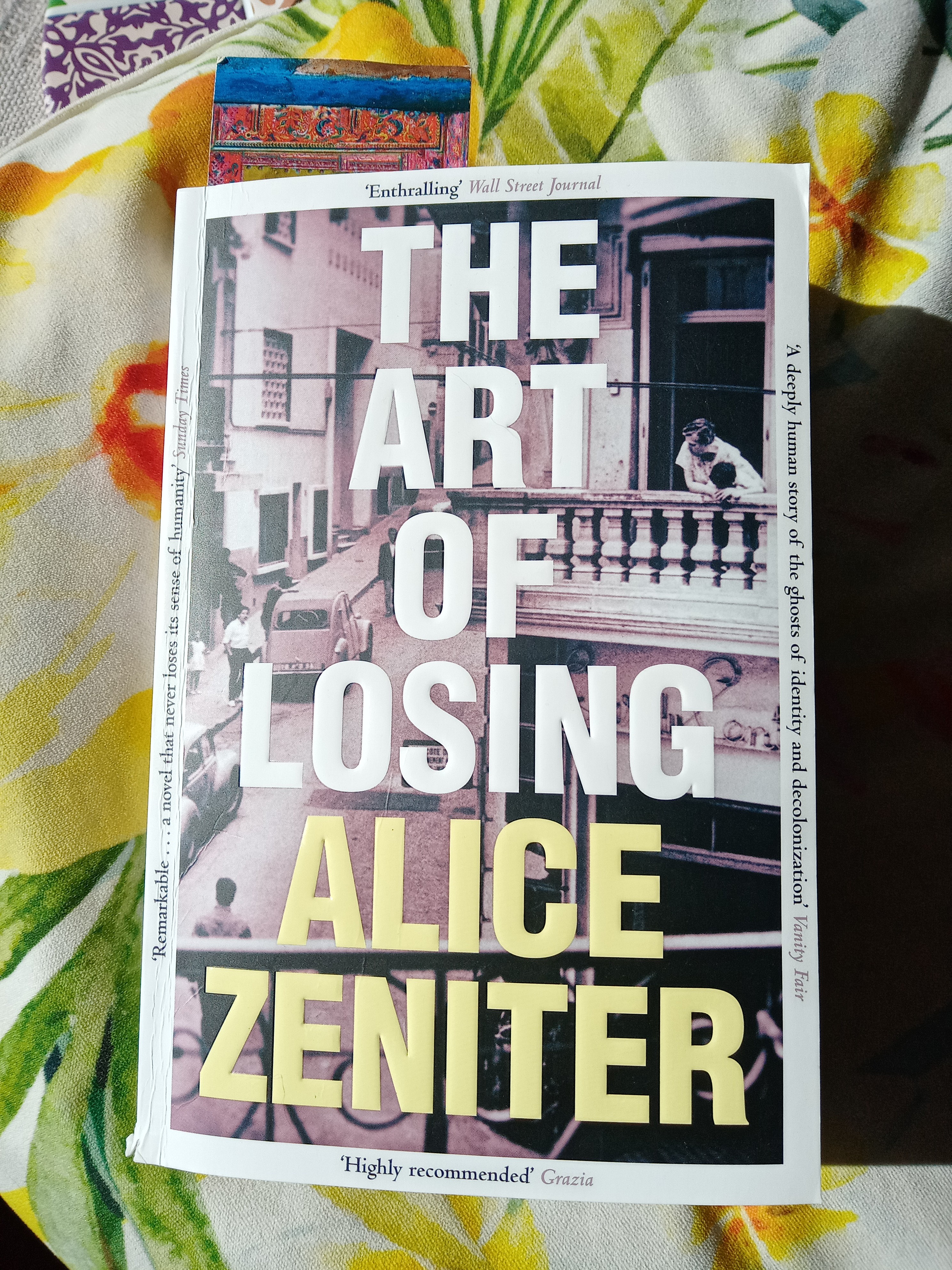

The Art of Losing by Alice Zeniter was the winner in 2022 of the Dublin Literary Award, an award where all books nominated are chosen by librarians around the world. As a result, this book went on to become the most borrowed book in Ireland, though it was nominated by the Bibliothèque publique d’information, France.

Three Generations of Family From 1930’s Algeria to Present Day Paris

Spanning three generations, beginning with Ali, born in a mountain village of the Kabyle region of northern Algeria, his son Hamid, also born there but whisked away to France with his parents in 1962, when threats and violence arrived in the village, endangering their lives, to Naima, born in France – the one who seeks answers to questions about who they are, why they had to leave and the stigma that surrounds their identity.

Written in three parts, each is an immersion in that era and life, showing how swiftly families change when they cross into another culture, how foreign they become to their own, how important it is to heal the wounds of the past, to acknowledge, understand and have tolerance for differences; how fear passes down ancestral lines, how connection is important.

Written in three parts, each is an immersion in that era and life, showing how swiftly families change when they cross into another culture, how foreign they become to their own, how important it is to heal the wounds of the past, to acknowledge, understand and have tolerance for differences; how fear passes down ancestral lines, how connection is important.

The prologue begins on a day near the end of what is to come. Naima has a hangover, a phrase repeats in her mind, her cousin’s words, demanding ‘Have you forgotten where you come from?’ She is preparing for an exhibition, an event that will take her back to her roots in Algeria.

As with many that use a prologue, it is a good idea to reread it after finishing the book, it has little context in the beginning. To be honest, I don’t find its placement at the beginning either helpful or intriguing. The book didn’t need it.

A Kabylian Mountain Village

And so we return to the 1930’s, a better place to begin the story.

In the 1930’s, Ali is a poor adolescent boy from Kabylia. Like most boys in his village, he is hesitating between breaking his back in small family fields dry as sand, tilling the lands of a colonist or some farmer richer than he is, or going down to the city, to Palestro, to work as a labourer.

The family fortune changes, first when their father dies in a rockslide, then when Ali and his brothers are caught in a flash flood and manage to not only save themselves, but trap a floating olive press that almost drowns them. It becomes key in changing their circumstance and before long they buy olive groves of their own.

The wealth of Ali and his brothers is a blessing that rains down upon a wider circle of cousins and friends, binding them into a larger, concentric community. It takes in many of the villagers, who are grateful. But it does not make every one happy. It overthrows the erstwhile supremacy of another family, the Amrouches, who, it is said, were rich back when lions still roamed.

Though it is 100 years since the colonisation of Algeria by the French, life in the mountainous hamlets still runs according to clannish loyalties. Rifts exist between villagers, each sides with their own clan, it brings no hatred or anger, in the early days it is simply a matter of pride, of honour. However, whenever there is a debate or decision, they naturally take opposite views.

A qaid (local leader appointed by the French) warns them of bandits, men who say they are fighting for the independence of the country, said to have been manipulated by Egyptian revolutionaries and Russian communists. When the freedom fighters appear, they will tell them they are not outlaws, ‘we are Kabyles, Muslims, like you’.

The villagers waver between exaltation and fear. Exaltation because everyone here believes that the French have no right to what the mountain lands offer to the Kabyles. Fear because of the word ‘we’, used so casually by this man that no one here has ever seen.

Things hot up and eventually they will be warned against listening to French propaganda and threaten those affiliated with them, (WW2 war veterans) should they continue to claim their war pension. This group become referred to collectively as harki. As will be their descendants, anyone who admits their family left in 1962.

First Generation Transition

When they flee to France, they are initially housed in the ‘Camp de Rivesaltes‘ and subsequently sent to a social housing community in Normandy. Hamid is the eldest of what will soon become a family of 10 children. He is the go-between, the first to receive the French education, to learn what is expected of them, to encounter racism, to want to escape the entrapment of a family that will always be seen as outsiders.

When they flee to France, they are initially housed in the ‘Camp de Rivesaltes‘ and subsequently sent to a social housing community in Normandy. Hamid is the eldest of what will soon become a family of 10 children. He is the go-between, the first to receive the French education, to learn what is expected of them, to encounter racism, to want to escape the entrapment of a family that will always be seen as outsiders.

Perhaps if his childhood had been like Clarisse’s, he would have done something else, he would have taken the time she suggested to to discover what he truly loves, what he wants to devote his days to doing, but he has not been able to shake off entirely the obligation of the utilitarian, the efficient, the concrete, nor has he been able to shake off a notion of the civil service as a grail where he is fortunate to be allowed to work.

At night, as he sets his alarm clock, he sometimes thinks that it takes much longer than he expected to escape, and that if he has not put as much distance between himself and his childhood as he would have liked, the next generation can carry on where he left off. He imagines that what he is really doing in the stifling little room that serves as his office is amassing shares in freedom that he will be able to pass on to his children.

He is free to marry for love, but he carries a legacy of silence into it. Outside the country of his birth, he is not judged like his father was for initially not producing a son. Hamid will raise only girls. One of them, Naima will tell their story.

“Every family is the site of a clash of civilizations.” Pierre Bourdieu, Sociologist, Algeria 1960

A Mystery of Identity and Repercussion for Multiple Generations

On discovering her father and therefore her family are referred to as harki, Naima sets out to discover what exactly this means and what her grandfather and others like him might have done to be so distrusted by their own. Despised at home and unwelcome in the country that has given them citizenship due to their efforts and support during WW2 – and left them stranded thereafter.

The path to acceptance is a lonely road and an almost impossible one without losing one’s identity completely; something must be let go, given up – each successive generation moves further away from their roots, knowing less and less about who they were.

The War That Made Heroes of Some & Traitors of Others

Naima’s investigation into her grandfather Ali’s past, reminds us of others who joined the cause to fight in WW2, of the Battle of Monte Cassino, in Italy. Like men from other colonial countries, he fought, yet as a consequence, for defending France, for being a war veteran, became perceived by many in his own country as a traitor.

As I read about this, I stopped and went to check a few of my own ancestral documents and sure enough, my grandfather too fought in the Battle of Monte Cassino, a raw subject he never talked of, that gave him nightmares for years. He lost his best friend there. In his division alone 1,600 New Zealanders lost their lives. These men were always regarded as heroes.

Looking Back, Healing Wounds, Learning Whose Version of a Story?

The Art of Losing brilliantly portrays these lives over three generations to bring Algerian history alive in a way that is rare to come across. Though there is a depth of research behind it, the pace never slows, in the hands of this storyteller, artfully using her characters, their relationships and circumstances to present an historical perspective and explain why sometimes silence and burying ones pain seem like the only way to survive, to manage disappointment. But then successive generations are challenged in relationships to break old patterns and heal wounds they may have inherited without even knowing the cause.

The novel ends with a retrospective art exhibition of a man Lalla, named in homage to Lalla Fatma N’Soumer (1830-1863) a Kabylan leader of resistance against the French, an Algerian Joan of Arc.

History is written by the victors, Naima thinks as she drifts off to sleep. This is an established fact, it is what makes it possible for history to exist in only one version. But when the vanquished refuse to admit defeat, when, despite their defeat, they continue writing their own version of history right up to the last second, when the victors for their part, write their history retrospectively to show the inevitability of their victory, then the contradictory versions on either side of the Mediterranean seem less like history than justifications or rationalizations sprinkled with dates and dressed up as history.

Perhaps that is what kept former residents of Bias so close to the camp they loathed; the could not bring themselves to break up a community that had reached an agreement on the version of history that suited them. Perhaps this is a foundation of communal life that is too often overlooked yet absolutely essential.

The original French version l’art de perdre was published in 2017, the English translation in 2021, and in Sept 2021 the French president Emmanuel Macron, made an official apology and asked for forgiveness for the French treatment of Algerian Harki fighters, for abandoning them during their home country’s war of independence. Trapped in Algeria, many were massacred as the country’s new leaders took brutal revenge. Thousand of others were placed in camps in France, often with their families, in degrading and traumatising conditions.

A Must Read novel. Highly Recommended.

Alice Zeniter, Author

Alice Zeniter was born in 1986. She is the author of four novels; Sombre dimanche (2013) won the Prix du Livre Inter, the Prix des lecteurs de l’Express and the Prix de la Closerie des Lilas; Juste avant l’oubli (2015) won the Prix Renaudot des lycéens.

Alice Zeniter was born in 1986. She is the author of four novels; Sombre dimanche (2013) won the Prix du Livre Inter, the Prix des lecteurs de l’Express and the Prix de la Closerie des Lilas; Juste avant l’oubli (2015) won the Prix Renaudot des lycéens.

l’art de perdre (2017) won the Prix Goncourt de Lycéens and 5 other French literary awards, in translation as The Art of Losing (2021) it won the Dublin Literary Award (2022) and was among the 20 top-selling Francophone books for two years in a row.

“I decided I wanted to learn more, but I wasn’t particularly interested in doing all this research for myself. My own self isn’t of huge interest to me, whereas anything that taps into the collective, and the political, this I care about.” Alice Zeniter

On her Inspiration from French sociologist Nicole Lapierre (author of Sauve qui peut la vie)

“…in it, she says that we need to learn how to tell their story like we do Odysseus’s. That migrant’s stories aren’t about pity, no, they’re about a never-ending journey, a story of craft and resourcefulness, of strength and beauty, of repeated departures, and until we manage to tell these stories in that way, we are abandoning them, leaving them to at best be pitied, and at worst be hated and feared. And that’s when I realised that the story I was researching, which dated from the early 1960s, completely echoed these current events. It is the story of populations locked in camps built far from urban centres, hidden away so that many will be able to say they didn’t know, that they don’t want to know or bother with these realities, with typhus and lice… This is when I realised that there might be an emergency to write about this motif, focusing on the fact that any migration is first an emigration, and removing that part from the story amputates people, it condemns them to misunderstandings. And that’s also when I decided to write this story in three acts. The emigration, the arrival which never really arrives and the third generation which, despite knowing nothing about the land of origin, has never been able to fully arrive either, as French people.”

Alice Zeniter is a a French novelist, translator, scriptwriter and director. She lives in Brittany.

Written in three parts, each is an immersion in that era and life, showing how swiftly families change when they cross into another culture, how foreign they become to their own, how important it is to heal the wounds of the past, to acknowledge, understand and have tolerance for differences; how fear passes down ancestral lines, how connection is important.

Written in three parts, each is an immersion in that era and life, showing how swiftly families change when they cross into another culture, how foreign they become to their own, how important it is to heal the wounds of the past, to acknowledge, understand and have tolerance for differences; how fear passes down ancestral lines, how connection is important.

When they flee to France, they are initially housed in the ‘

When they flee to France, they are initially housed in the ‘ Alice Zeniter was born in 1986. She is the author of four novels; Sombre dimanche (2013) won the Prix du Livre Inter, the Prix des lecteurs de l’Express and the Prix de la Closerie des Lilas; Juste avant l’oubli (2015) won the Prix Renaudot des lycéens.

Alice Zeniter was born in 1986. She is the author of four novels; Sombre dimanche (2013) won the Prix du Livre Inter, the Prix des lecteurs de l’Express and the Prix de la Closerie des Lilas; Juste avant l’oubli (2015) won the Prix Renaudot des lycéens. At only 76 pages, it is a brief recollection that begins in quiet, dramatic form as she recalls the day her father, at the age of 67, unexpectedly, quite suddenly dies.

At only 76 pages, it is a brief recollection that begins in quiet, dramatic form as she recalls the day her father, at the age of 67, unexpectedly, quite suddenly dies. Ernaux’s father was fortunate to remain in education until the age of 12, when he was hauled out to take up the role of milking cows. He didn’t mind working as a farmhand. Weekend mass, dancing at the village fetes, seeing his friends there. His horizons broadened through the army and after this experience he left farming for the factory and eventually they would buy a cafe/grocery store, a different lifestyle.

Ernaux’s father was fortunate to remain in education until the age of 12, when he was hauled out to take up the role of milking cows. He didn’t mind working as a farmhand. Weekend mass, dancing at the village fetes, seeing his friends there. His horizons broadened through the army and after this experience he left farming for the factory and eventually they would buy a cafe/grocery store, a different lifestyle. Born in 1940,

Born in 1940,  Originally published in French as Amour, colère et folie, this trilogy of novellas was originally suppressed upon its initial publication in 1968. Seen as a scathing response to the struggles of race, class and sex that had occurred in Haiti, this major work became an underground classic, would send its author into exile and would finally be released in an authorised edition in France in 2005 (this English version in 2009).

Originally published in French as Amour, colère et folie, this trilogy of novellas was originally suppressed upon its initial publication in 1968. Seen as a scathing response to the struggles of race, class and sex that had occurred in Haiti, this major work became an underground classic, would send its author into exile and would finally be released in an authorised edition in France in 2005 (this English version in 2009). Marie Vieux-Chauvet was a Haitian novelist, poet and playwright, the author of five novels including Dance on the Volcano, Fonds des Negres, Fille d’Haiti and Les Rapaces.

Marie Vieux-Chauvet was a Haitian novelist, poet and playwright, the author of five novels including Dance on the Volcano, Fonds des Negres, Fille d’Haiti and Les Rapaces. I’ve read one other novel by Delphine de Vigan, which was auto-fiction and delved into lives affected by a bi-polar parent. A later novel also sat on the edge of fiction and real life, a novel of suspense where a friendship becomes obsessive and perhaps dangerous.

I’ve read one other novel by Delphine de Vigan, which was auto-fiction and delved into lives affected by a bi-polar parent. A later novel also sat on the edge of fiction and real life, a novel of suspense where a friendship becomes obsessive and perhaps dangerous. The narrative switches between the two as first Marie recalls the day everything changed, when Michka lost her independence and then moments are shared while she is in care, Michka’s conversation affected by her aphasia, the impairment of her use of language, other words jump ahead pushing out the one she wishes to say.

The narrative switches between the two as first Marie recalls the day everything changed, when Michka lost her independence and then moments are shared while she is in care, Michka’s conversation affected by her aphasia, the impairment of her use of language, other words jump ahead pushing out the one she wishes to say.