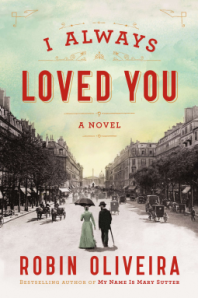

While looking at a Goodreads list of Historical Fiction due out in 2014, I noticed the name Robin Oliveira, author of the excellent novel My Name is Mary Sutter published in 2010.

While looking at a Goodreads list of Historical Fiction due out in 2014, I noticed the name Robin Oliveira, author of the excellent novel My Name is Mary Sutter published in 2010.

I don’t read a lot of historical fiction, but occasionally via word of mouth, I hear about a well written, compelling title that I can’t resist, particularly if it is set in France.

Well researched historical fiction in the hands of a talented writer, is my preferred method of learning about French history (or any history); engaging characters propel the narrative forward and we invest ourselves in the characters who have inhabited the period and discover the chronology of events as if we are living them. Historical events when presented without the force, nuance and characteristic dialogue of personalities that have shaped them, risk becoming dry, uninteresting, sedative and read by the few.

Set in 19th century America on the cusp of civil war, My Name is Mary Sutter chronicles the life of a midwife with ambitions to become a surgeon, something she will be thrown into with the advent of war. Her ambition requires the courage to cope with an abundance of men suffering war injuries amid dire living/working conditions plus sacrifices in her personal and family life. She is a captivating heroine, strong-willed yet vulnerable, living in an incredible pioneering era for women.

In her research, the author learned that 17 young women became physicians after their nursing experiences in the civil war. While Mary Sutter is fictional, she is a truly inspired character about whom Robin Oliveira had this is say:

“And through it all there was Mary Sutter, whose story I needed to tell as a celebration of women who seize the courage to live on, to thrive, to strive, even, when men conspire to war. Mary, flawed and intelligent, careening between desire and remorse, stumbling forward out of courage and stubbornness, hiding a broken heart, but hoping to redeem something beautiful from a life humbled by regret.”

Which is a prelude to saying that seeing a new Robin Oliveira novel coming out in 2014 and set in France, I jumped at the chance to read it.

I Always Loved You, an unfortunate and slightly off-putting title, sorry, is about the life of the American painter Mary Cassatt, her life in Paris struggling to make her name while remaining true to her art, and enduring a life-long fractious relationship with the impressionist painter and sculptor Edgar Degas. It also brings to life another female painter, Berthe Morisot and her relationship with the Manet brothers, Édouard and Eugène.

I Always Loved You, an unfortunate and slightly off-putting title, sorry, is about the life of the American painter Mary Cassatt, her life in Paris struggling to make her name while remaining true to her art, and enduring a life-long fractious relationship with the impressionist painter and sculptor Edgar Degas. It also brings to life another female painter, Berthe Morisot and her relationship with the Manet brothers, Édouard and Eugène.

Mary had left her home town of Philadelphia to pursue artistic ambitions and after ten years of hard work, having once been accepted by the Salon for her work Ida (or Spanish Dancer Wearing a Lace Mantilla), has now been rejected and is feeling disillusioned and on the point of giving in to her father who wants her to return home, find a husband and be with her family. Had it not been for his fascination with Ida and the subsequent encounter with Degas, she may well have fulfilled her father’s bidding.

“C’est vrai. Voilá quelqu’un qui sent comme moi.”

(It’s true. Here it is, someone who feels as I do).

Edgar Degas commenting on Mary Cassatt’s painting, Ida

Through Mary, we learn what it meant to be a painter in Paris in the late 1800’s, the restrictive, suffocating influence of the Salon Jury, purveyors of the official annual exhibition of the Académie des Beaux-Arts, known as the Salon de Paris, to whom all artists looking for acknowledgement and recognition would submit one or two paintings and then await acceptance or rejection. Those deemed successful by the Jury would be hung at the next exhibition and if lucky, talked up by the critics. Those who weren’t, were resigned to another year of work before resubmitting – and they all did, for it was seen as essential to exhibit there in order to achieve any success, a status quo that existed for almost 200 years in France.

Salon de Louvre 1787

Source:Wikipedia

This process spurned a rebel group lead by Edgar Degas who refused to submit their work to the Salon Jury and began to hold an alternative exhibition. These artists were willing to let go of the past with their references and rules and were bold with colour, subject and loose with their interpretation. They became referred to disparagingly by the media as Impressionists, a term Degas despised. It was a brave move and not all of the groups members managed to sustain their nerve, the lure of the Salon despite its limitations, not easy to stand up against.

Degas had admired Mary Cassatt’s work without knowing who she was and after organising to meet her, invited her to exhibit with his group of artists and to one of their weekly salons, a social gathering that included Édouard Manet, his brother Eugène, Berthe Morisot, Renoir, the writer Émile Zola, Pissarro, Gustave Caillebotte, Zacharie Astruc, the poet Stéphane Mallarmé and Claude Monet among others. The evening would mark the beginning of a long relationship between two talented artists whose work came before all else and whose similarities and stubbornness would continue to attract and repel them until their last days.

“He was right. The something, the leap an artist makes so that his painting is more than its technique, he had already achieved. And she wanted that.”

Edouard Dantan

Un Coin du Salon, 1880

Source: Wikipedia

I had never heard of Mary Cassatt when I began reading and was intrigued to discover her art, but decided not to go looking at her or Degas’s work until I had finished, allowing my imagination to create an image of their creations during the period of their encounters, which added an exciting anticipation to the reading, especially while Cassatt was preparing for her first showing with the Impressionists and when Degas was working on his sculpture The Dancer.

I hesitate to show any of images of their art here, as it was such a reward for me upon finishing the book. Getting to know or reacquainting ourselves with the artists work is a personal journey and we should decide in our own time when to view the oeuvres of these great artists. No Spoilers here!

They were an inspiration to each other with regard to their work and Oliveira brings the two alive in rich detail, you can almost see their respective studios and smell the turpentine, imagining the furrowed brow of concentration as these two passionate artists throw themselves into their work and block out the world around them.

What they couldn’t inject into their relationship, they gifted to each other through their work, some of the most poignant and yet ironic scenes are when Degas helps Cassatt find her subject and confirms what it is she should be painting. And then the joy of finally seeing them and seeing the energy and vibrancy of those paintings she created during that period when they responded so positively to each others influence, fact or fiction, it stands out in the work.

“I have no money to pay a model,” Mary said to Degas. “I don’t know what to do.”

“You must find your subject.”

Mary said, “Like yours? Ballet, horses, brothels?”

“Obsessions are an artist’s gift. Obsession is poetry,” Degas said.

Just as other writers have brought alive the Lost Generation of writers resident in Paris in the 1920’s, Robin Oliveira does the same for this group of painters, awakening our interest in this turning point in the history of art and the influence of this group on painters in the wider world, which continues today. It is a brilliantly told story of fascinating characters and their passion for art.

National Gallery of Art

Washington

And if you are fortunate enough to live near or visit Washington, it appears that there is to be an exhibition of Cassatt and Degas’s work at the National Gallery of Art May 14 – Oct 5 focused on the critical period of the late 1870s through the mid-1880s when Degas and Cassatt were closest, bringing 70 various works together to showcase the fascinating artistic dialogue that developed between these two major talents and friends.

Note: This book was an ARC (Advance Readers Copy) provided by the publisher via NetGalley.