Back in January, the Dublin Literary Award 2024 announced a longlist of 70 books nominated by 80 libraries including librarians and readers, from 35 countries around the world.

Six novels have now been shortlisted for the award, featuring authors who are American, Canadian, Australian, Romanian and Irish, nominated by public libraries in Romania, Germany, Jamaica, Canada and Australia.

The only one I have read, and it was a 5 star read for me is Sebastian Barry’s Old God’s Time (see my review here) I include the judges’ comments below to help you decide if you are interested in reading any of the nominated titles.

Solenoid sounds interesting and has been highly praised, but 840 pages is too grand of an ask for this reader. Praiseworthy is tempting, but again 740 pages!

The Shortlist of Six Novels

Old God’s Time by Sebastian Barry (Ireland) (literary fiction)

– Retired policeman Tom Kettle is enjoying the quiet of his new home in Dalkey, overlooking the sea. His peace is interrupted when two former colleagues turn up at his door to ask about a traumatic, decades-old case. A case that Tom never came to terms with. His peace is further disturbed by a young mother who asks for his help. And what of Tom’s wife, June, and their two children? A beautiful, haunting novel about what we live through, what we live with, and what will survive of us.

Judges’ Comments

Old God’s Time by Sebastian Barry is a book about love. It’s a world of precarious balancing, a high wire act in which the ghosts of the past intermingle with the challenges of the present. Here a retired policeman settling into a new stage in his life faces the legacy of an old case. This exploration of trauma, childhood abuse in catholic institutions, memory and the lingering impact of loss is devastating. It deftly avoids the trap of solely being one note in that regard. Barry does something clever here where he elevates the work beyond the confines of its themes into a reading experience that often feels transcendent despite the painful subject matter. It’s impossible to read this novel and not be moved by its mercurial power, the ways in which it shifts ideas of human consciousness. This is a beautiful and, in some ways, tender work. Full of heart, risk and that illusive, rare quality the best storytellers possess, it marks Barry, one of our most gifted talents as a writer who continues to invigorate the novel form.

‘Outstanding, a revelatory and deeply affecting work. Barry’s meditation on trauma, memory and loss is a book about love that lingers in the body long after reading it.’ — Irenosen Okojie, 2024 Dublin Literary Award Judge

Solenoid by Mircea Cărtărescu, translated by Sean Cotter (Romania)

– Based on Cărtărescu’s own role as a high school teacher, Solenoid begins with the mundane details of a diarist’s life and spirals into a philosophical account of life, history, philosophy, and mathematics.

On a broad scale, the novel’s investigations of other universes, dimensions, and timelines reconcile the realms of life and art. Grounded in the reality of late 1970s/early 1980s Communist Romania, including long lines for groceries, the absurdities of the education system, and the misery of family life.

Combining fiction, autobiography and history, Solenoid ruminates on the exchanges possible between the alternate dimensions of life and art within the Communist present.

Judges’ Comments

We can imagine (it not fully grasp) a world that has, in comparison to our own, an extra dimension.” In some respects, this is the world of Solenoid. The city of Bucharest in which the narrator is a teacher and failed writer is a place in which what appears to be an abandoned factory contains unexpected caverns, tunnels and a gallery of enormous parasites, where an apparently ordinary, run-down house is built upon an electrical device that causes people lying in bed to float. By turns wildly inventive, philosophical, and lyrical, with passages of great beauty, Solenoid is the work of a major European writer who is still relatively little known to English-language readers. Sean Cotter’s translation of the novel sets out to change that situation, capturing the lyrical precision of the original, thereby opening up Cărtărescu’s work to an entirely new readership.

‘An anti-novel that for all intents and purposes should not exist but still does despite itself, thanks to the overpowering talents of the author and the translator.’ — Anton Hur, 2024 Dublin Literary Award Judge

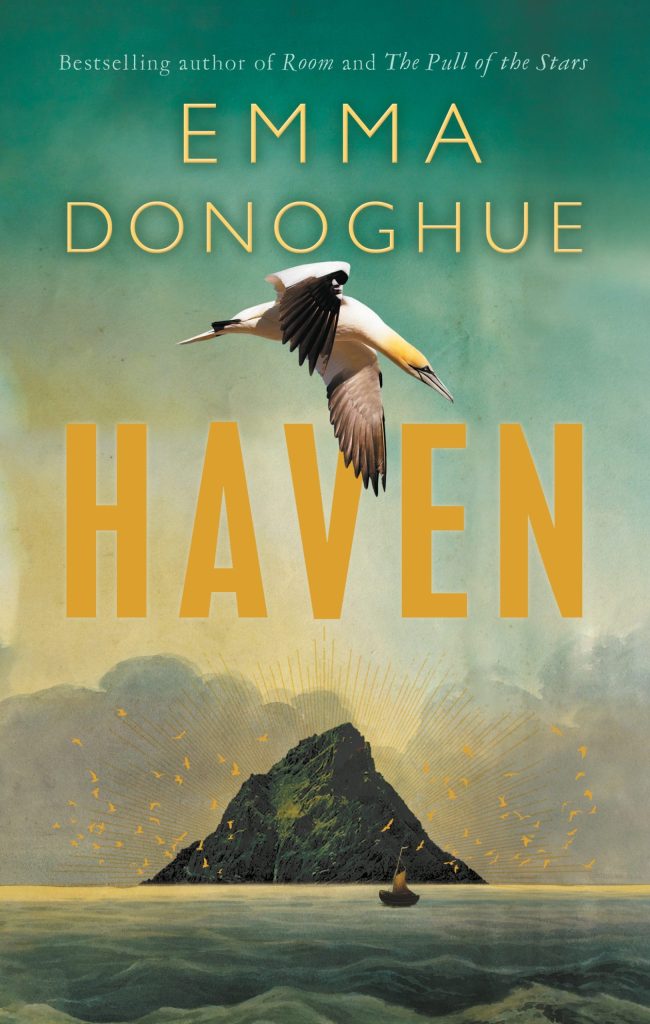

Haven by Emma Donoghue (Ireland) (historical fiction)

– In 7th-century Ireland, a scholar/priest called Artt has a dream telling him to leave the sinful world behind. Taking two monks – young Trian & old Cormac – he rows down the river Shannon in search of an isolated spot on which to found a monastery. With only faith to guide them and drifting out into the Atlantic, the three men find a steep, bare island, inhabited by tens of thousands of birds, and claim it for God. In such a place, what will survival mean? What they find is the extraordinary island now known as Skellig Michael.

Judges’ Comments

A novel of stylistic precision yet ethical complexity, Haven tells the story of three monks in seventh-century Ireland in search of a place of retreat from worldly temptation. Their journey by boat to a barren islet allows the com- plex interaction between experience and idealism to be revealed and subtly explores the importance of evolving human bonds in shaping community. Haven’s searching treatment of authority, and the tensions between rigid beliefs and openness of thought, extend beyond interpersonal dynamics to our relationship with the natural environment. The world Emma Donoghue creates in this novel is at once strange and familiar, provoking us to think deeply about the importance of human empathy in navigating our place on this earth.

‘A novel of stylistic precision yet ethical com- plexity, Haven offers a searching treatment of authority, examining the implications of fixed beliefs for our relationships with each other and with the more-than-human world.’ — Lucy Collins, 2024 Dublin Literary Award Judge

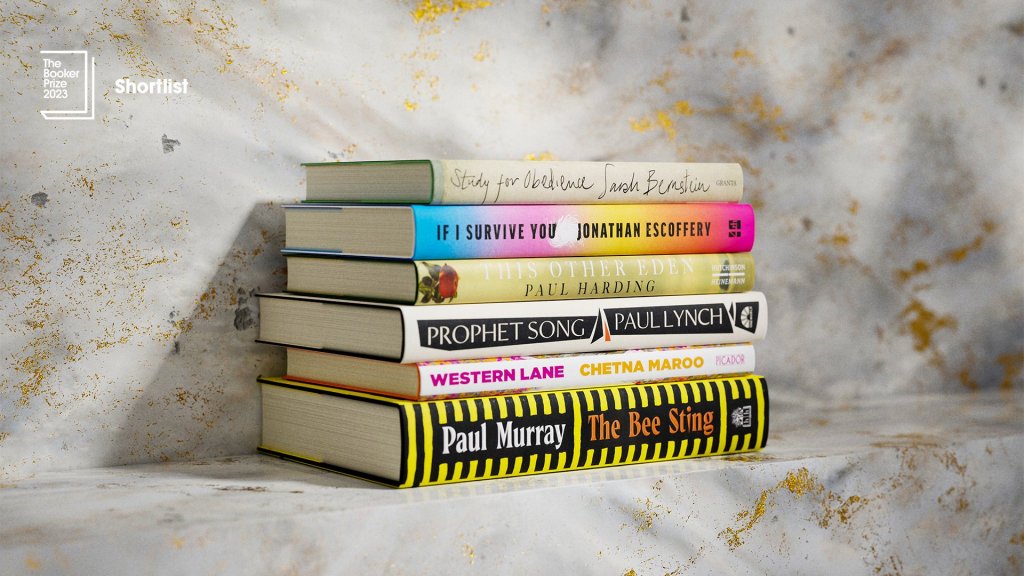

If I Survive You by Jonathan Escoffery (USA/Jamaica) (Short Stories)

– In the 1970s, Topper and Sanya flee to Miami as political violence consumes their native Kingston. But America, as the couple and their two children learn, is far from the promised land. Excluded from society as Black immigrants, the family pushes on first through Hurricane Andrew and later the 2008 recession. But even as things fall apart, the family remains motivated by what their younger son calls “the exquisite, racking compulsion to survive.”

Pulsing with vibrant lyricism and sly commentary, Escoffery’s debut unravels what it means to be in between homes and cultures in a world at the mercy of capitalism and white supremacy.

Judges’ Comments

Jonathan Escoffery’s energetic novel-in-stories, If I Survive You, follows a Jamaican family living hand-to-mouth in Florida. The different members of the family search for a foothold in this new and exhausting country, each in their own way, struggling against poverty, racism, recession and hurricanes. At the heart of the story lies a deep-rooted racial ambiguity; where does one belong and is it possible to be “a little of this and a little of that” and still find your way, find your people, find a future? The story also deals with the universal condition of fatherly rejection and sibling rivalry, with a remarkable eye for perfect de- tails. The narrative is vibrant, humorous, snappy and quietly devastating; eight interlinking stories told by various voices, often from an urgent and empathetic second-person point of view, and also in Jamaican dialect, that describe how life keeps knocking the family back in their pursuit of identity and happiness.

‘A fresh voice in fiction, Jonathan Escoffery blurs the lines between the short story and the novel in a work that brings us into the lives of Jamaican-Americans in Miami. Through linked stories, the form mirrors the lives of the characters and their struggles to connect, both with their families, and with the society around them.’ — Chris Morash, 2024 Dublin Literary Non-Voting Chair

The Sleeping Car Porter by Suzette Mayr (Canada) (Historical Fiction)

– It’s 1929, and Baxter is considered lucky, as a Black man, to have a job as a porter on a train that crisscrosses the continent. He has to smile and nod for the white passengers when they call him ‘George.’ He’s obsessed with teeth, and saving up tips for dentistry school.

On this trip, the passengers are unruly, especially when the train is stranded for days – their secrets leak out, blurring with Baxter’s sleep-deprivation hallucinations. When he finds an illicit postcard of two men, Baxter’s longings are reawakened; keeping it puts his job in peril, but he can’t part with it or his memories of a certain Porter Instructor.

Judges’ Comments

An unconventional historical novel that combines meticulous research and deep imagination, The Sleeping Car Porter by Suzette Mayr takes readers on a vividly depicted train ride in the 1920’s from the perspective of a Black and queer sleeping car porter as he tries to make a life that is a little less precarious and a lot more hopeful despite the odds stacked against him. As the train travels through the rural Canadian landscape, Baxter, the porter of the title, similarly traverses the vistas of memory, the reality that surrounds him, and his hopes and visions of the future on his own interior journey of discovery and self-creation. Written in a concise yet evocative style, this slim novel combines the epic scope of history with the lift and verve of ghost stories and queer narrative, creating a quietly propulsive read that at the same time takes stock of an entire life in the space of a single train voyage.

“He drinks melting glacier, plunges his hands into the water past the point of ice just to wake himself up and calm himself down. He ascends into the vestibule, his legs shaky, his hands icy numb.”

‘You can almost taste the exhaustion and despair in this quiet, yet vivid, story of a black man working as a porter on a sleeper train in Canada in 1929. Beautifully written, melancholy but never without hope.’— Ingunn Snaedel, 2024 Dublin Literary Award Judge

Praiseworthy by Alexis Wright (Australia) (Literary fiction)

– In a small town in northern Australia dominated by a haze cloud, a crazed visionary sees donkeys as the solution to the global climate crisis and the economic dependency of the Aboriginal people. His wife seeks solace from his madness in the dance of moths and butterflies. One of their sons, called Aboriginal Sovereignty, is determined to commit suicide. The other, Tommyhawk, wishes his brother dead so that he can pursue his dream of becoming white and powerful.

Praiseworthy is a novel which pushes allegory and language to its limits, a cry of outrage against oppression and disadvantage, and a fable for the end of days.

Judges’ Comments

Alexis Wright’s Praiseworthy is a wonder of twenty-first century fiction. This modernist more-than-an-allegory about a pernicious haze that settles over a northern Australia town yokes a painfully contemporary tale of political, social and climatic disaster to a narrative consciousness embodying 65,000 years of aboriginal survival. Intimate while epic, the family drama at its center reads like chamber music on a symphonic scale. Wright has authored a blisteringly funny book, replete with situations and speech that elicit wild laughter – a laughter through tears we may recognize from our readings of Beckett and Kafka. She has also written a beautiful one: time and again Praiseworthy delivers unforgettable images, from ‘aerial rivers’ of dancing butterflies to hordes of stinking donkeys. Startlingly original, fiercely political, uncompromising in every respect, Praiseworthy expands the possibility of the novel form.

‘Funny and fierce, Alexis Wright’s Praiseworthy is a wonder of twenty-first century fiction. This modernist more-than-an-allegory yokes a painfully contemporary tale of political, social and climatic disaster to a narrative consciousness embodying 65 000+ years of aboriginal survival.’ — Daniel Medin, 2024 Dublin Literary Award Judge

Reading From Libraries

The novels nominated and shortlisted for the Award will be available for readers to borrow from Dublin City Libraries and from public libraries around Ireland, or can be borrowed as eBooks and some as eAudiobooks on the free Borrowbox app, available to all public library users.

Have you read any of the shortlist? Are you tempted by any of these titles? Let me know in the comments below.