This poetic musical installation, entitled Harmonic Fields in English, came to my attention three months ago when I was searching for something interesting to write in the ‘To Do’ section of the destination guide on Marseilles I (used to) write for a magazine.

I knew it wouldn’t be too hard to find something spectacular, as Marseilles has been designated cultural capital of Europe for 2013, a prestigious event on the cultural calendar and one that has resulted in much-needed expenditure giving this seaside city something of a facelift.

I will save the wondrous changes in the city for another post, but yesterday my children and I drove into Marseilles and along the corniche to Les Goudes. I do love that word corniche , the English equivalent doesn’t evoke quite the same warm, exciting, air of anticipation feeling as corniche.

The corniche (roughly translated as ledge, more naturally translated as cliff road or coast road) winds its way from the centre of Marseilles, La Vieux Port past all the beaches and seaside restaurants, beach parks, cafes, cliff-front residences, joggers, sun-seekers and finishes in Les Goudes, which signals the beginning of Les Calanques, huge limestone cliff faces which make it nearly impossible to access the coastline between Marseilles and Cassis, except by boat or on foot. But the rewards for doing so are spectacular.

Champ Harmonique is the brainchild of Pierre Sauvageot, inspired by the wind and natural instruments of Indonesia, which require no player but the wind and can hang from trees or be placed in nature, allowing her to be playful, moody or melodramatic.

The coastline of Marseilles in the region of Provence could not be more perfect, natures favourite elements here are the sun and the wind, the one we know best from the north-east is the Mistral, but there are many others and yesterday we had a less dramatic, more playful wind, speeding up, then slowing down, her presence never more known and her subtleties never more appreciated than when given something like this spectacular installation to play with.

Nature gets to play here with cellos, drum shakers, glockenspiels, bamboo poles that sing, spinning music boxes, and a lot of other things I can’t even begin to translate like hélices-sirènes, épouvantails balinais, tepees chromatiques, graals pentatoniques, arcs sonores, arbres à flûtes, cannes à pêche à lacrotale… 500 instruments in total.

It is a poetic symphony to experience and cannot (and should not says Pierre Sauvageot) be captured easily on film, but the stunning environment must be shared and if you have the occasion to visit the south of France during 2013, this is merely a taste of the events happening during the Marseilles Provence cultural capital celebrations.

Champ Harmonique is open until the 28th April in Les Goudes, Marseilles. It’s free to enter and the installation is supervised on Thursday, Friday and Saturdays and although it is open and accessible at all other times, some of the instruments are disabled during the unattended periods.

Champ Harmonique is open until the 28th April in Les Goudes, Marseilles. It’s free to enter and the installation is supervised on Thursday, Friday and Saturdays and although it is open and accessible at all other times, some of the instruments are disabled during the unattended periods.

In true French style, (a sit down leisurely lunch remains a significant priority here for all), the installation is closed every day from 12–2pm.

And there will be a special open air concert on the evening of the 25th, the night of the full moon!

To imagine what the experience might have felt like and to see the view, here’s a three minute video, captured during the time it was open.

, and she answers from her tree a little way off,

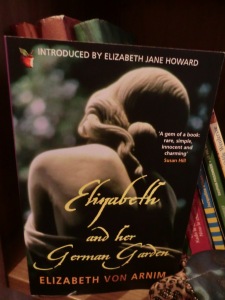

, and she answers from her tree a little way off, , beautifully assenting to and completing her lord’s remark, as becomes a properly constructed German she-owl. They say the same thing over and over again so emphatically that I think it must be something nasty about me; but I shall not let myself become frightened away by the sarcasm of owls.

, beautifully assenting to and completing her lord’s remark, as becomes a properly constructed German she-owl. They say the same thing over and over again so emphatically that I think it must be something nasty about me; but I shall not let myself become frightened away by the sarcasm of owls.

In 1996 I spent three months travelling in Asia, limiting my visit to four countries, India, Nepal, Vietnam and Thailand.

In 1996 I spent three months travelling in Asia, limiting my visit to four countries, India, Nepal, Vietnam and Thailand.