This £1000 prize was established by the University of Warwick in 2017 to address the gender imbalance in translated literature and to increase the number of international women’s voices accessible by a British and Irish readership. The list includes titles published in the UK, translated into English.

In 2020, A Multi-generational Saga

Last year the prize was awarded to The Eighth Life (a family saga that begins with the daughters of a Georgian chocolatier, through wars, revolutions and generations), by Nino Haratischvili, translated from German by Charlotte Collins and Ruth Martin.

The 2021 prize is judged by Amanda Hopkinson, Boyd Tonkin and Susan Bassnett.

“These long-listed titles not only span cultures and continents from China to Georgia, and from Thailand to Poland, they also cover a spectrum of literary forms. The list includes poetry, fiction of many kinds – from futuristic fables to family sagas – as well as a range of imaginative non-fiction, from family memoir and biographical essay to social history.

In every case, the artistry of the translator keeps pace with the invention of the author. Each book created its own world in its own voice. The judges warmly recommend them all.”

The 2021 Longlist

From 115 eligible entries representing 28 languages, seventeen titles have been longlisted for the prize. (Book descriptions below are extracted via Goodreads)

The longlist covers ten languages with French, German, Japanese and Russian represented more than once. Translations from Georgian and Thai are represented on the longlist for the first time in 2021.

Maria Stepanova and her translator from Russian Sasha Dugdale feature twice on the longlist with In Memory of Memory (Fitzcarraldo Editions) and War of the Beasts and the Animals (Bloodaxe Books). Also longlisted are previous winners of the prize Annie Ernaux and translator Alison L. Strayer who won in 2019 for The Years. Writers Jenny Erpenbeck, Hiromi Kawakami, Esther Kinsky and Yan Ge, and translators Elisabeth Jaquette, Frank Wynne, are all on the longlist for the second time.

The shortlist for the prize will be published in early November. The winner will be announced at a ceremony on Wednesday 24 November.

The Longlist

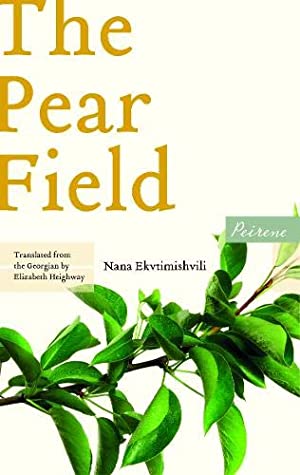

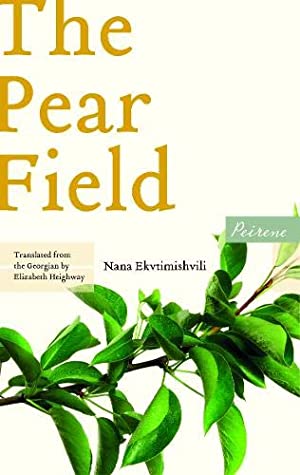

Nana Ekvtimishvili, The Pear Field, translated from Georgian by Elizabeth Heighway (Fiction/Historical) (Peirene Press, 2020)

In post-soviet Georgia, on the outskirts of Tbilisi, on the corner of Kerch St., is an orphanage. Its teachers offer pupils lessons in violence, abuse and neglect. Lela is old enough to leave but has nowhere else to go. She stays and plans for the children’s escape, for the future she hopes to give to Irakli, a young boy in the home. When an American couple visits, offering the prospect of a new life, Lela decides she must do everything she can to give Irakli this chance.

In post-soviet Georgia, on the outskirts of Tbilisi, on the corner of Kerch St., is an orphanage. Its teachers offer pupils lessons in violence, abuse and neglect. Lela is old enough to leave but has nowhere else to go. She stays and plans for the children’s escape, for the future she hopes to give to Irakli, a young boy in the home. When an American couple visits, offering the prospect of a new life, Lela decides she must do everything she can to give Irakli this chance.

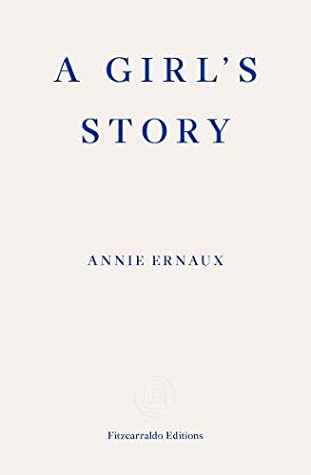

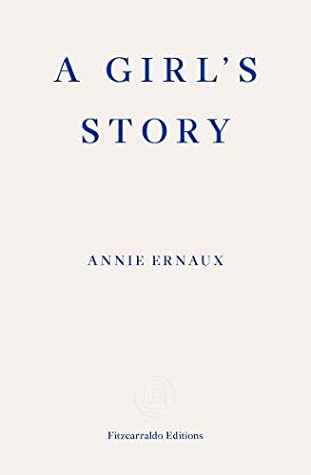

Annie Ernaux, A Girl’s Story, translated from French by Alison L. Strayer (Fitzcarraldo Editions, 2020) (Memoir)

Annie Ernaux revisits the summer of 1958, spent working as a holiday camp instructor in Normandy, and recounts the first night she spent with a man. When he moves on, she realizes she has submitted her will to his and finds that she is a slave without a master. Now, sixty years later, she finds she can obliterate the intervening years and return to consider this young woman whom she wanted to forget completely. In writing A Girl’s Story, which brings to life her indelible memories of that summer, Ernaux discovers that here was the vital, violent and dolorous origin of her writing life, built out of shame, violence and betrayal.

Annie Ernaux revisits the summer of 1958, spent working as a holiday camp instructor in Normandy, and recounts the first night she spent with a man. When he moves on, she realizes she has submitted her will to his and finds that she is a slave without a master. Now, sixty years later, she finds she can obliterate the intervening years and return to consider this young woman whom she wanted to forget completely. In writing A Girl’s Story, which brings to life her indelible memories of that summer, Ernaux discovers that here was the vital, violent and dolorous origin of her writing life, built out of shame, violence and betrayal.

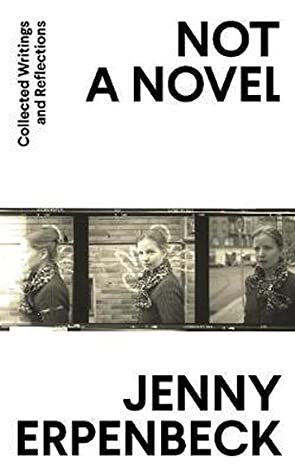

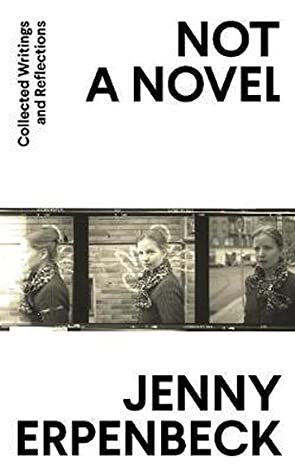

Jenny Erpenbeck, Not a Novel, translated from German by Kurt Beals (Granta, 2020) (Essays/Nonfiction)

A collection of intimate and explosive essays on literature, life, history, politics and place. Drawing from her 25 years of thinking and writing, the book plots a journey through the works and subjects that have inspired and influenced her.

A collection of intimate and explosive essays on literature, life, history, politics and place. Drawing from her 25 years of thinking and writing, the book plots a journey through the works and subjects that have inspired and influenced her.

Written with the same clarity and insight that characterize her fiction, the pieces range from literary criticism and reflections on Germany’s history, to the autobiographical essays where Erpenbeck forgoes the literary cloak to write from a deeply personal perspective about life and politics, hope and despair, and the role of the writer in grappling with these forces.

Yan Ge, Strange Beasts of China, translated from Chinese by Jeremy Tiang (Fantasy/Science Fiction) (Tilted Axis Press, 2020)

In the fictional Chinese town of Yong’an, human beings live alongside spirits and monsters, some of almost indistinguishable from people. Told in the form of a bestiary, each chapter introduces us to a new creature – from the Sacrificial Beasts who can’t seem to stop dying, to the Besotted Beasts, an artificial breed engineered by scientists to be as loveable as possible. The narrator, an amateur cryptozoologist, is on a mission to track down each breed, but in the process discovers that she might not be as human as she thought.

In the fictional Chinese town of Yong’an, human beings live alongside spirits and monsters, some of almost indistinguishable from people. Told in the form of a bestiary, each chapter introduces us to a new creature – from the Sacrificial Beasts who can’t seem to stop dying, to the Besotted Beasts, an artificial breed engineered by scientists to be as loveable as possible. The narrator, an amateur cryptozoologist, is on a mission to track down each breed, but in the process discovers that she might not be as human as she thought.

Hiromi Kawakami, People from My Neighbourhood, translated from Japanese by Ted Goossen (short stories/magic realism) (Granta, 2020)

From the author of the internationally bestselling Strange Weather in Tokyo, a collection of interlinking stories that blend the mundane and the mythical—“fairy tales in the best Brothers Grimm tradition: naif, magical, and frequently veering into the macabre”.

From the author of the internationally bestselling Strange Weather in Tokyo, a collection of interlinking stories that blend the mundane and the mythical—“fairy tales in the best Brothers Grimm tradition: naif, magical, and frequently veering into the macabre”.

A bossy child who lives under a white cloth near a tree; a schoolgirl who keeps doll’s brains in a desk drawer; an old man with two shadows, one docile and one rebellious; a diplomat no one has ever seen goes fishing on a lake no one has heard of. These are some of the inhabitants of this neighbourhood. In their lives, details of the local and everyday—the lunch menu at a tiny drinking place called the Love, the color and shape of the roof of the tax office—slip into accounts of duels, prophetic dreams, revolutions, and visitations from ghosts and gods.

Mieko Kawakami, Breasts and Eggs, translated from Japanese by Sam Bett and David Boyd (Fiction/Feminism) (Picador, 2020)

Breasts and Eggs explores the inner conflicts of an adolescent girl who refuses to communicate with her mother except through writing.

Breasts and Eggs explores the inner conflicts of an adolescent girl who refuses to communicate with her mother except through writing.

Through the story of these women, Kawakami paints a portrait of womanhood in contemporary Japan, probing questions of gender and beauty norms and how time works on the female body.

Esther Kinsky, Grove, translated from German by Caroline Schmidt (Fiction/Travel) (Fitzcarraldo Editions, 2020)

An unnamed narrator, recently bereaved, travels to Olevano, a small village south-east of Rome. It is winter, and from her temporary residence on a hill between village and cemetery, she embarks on walks and outings, exploring the banal and the sublime with equal dedication and intensity. Seeing, describing, naming the world around her is her way of redefining her place within it. Written in a rich and poetic style, Grove is an exquisite novel of grief, love and landscapes.

An unnamed narrator, recently bereaved, travels to Olevano, a small village south-east of Rome. It is winter, and from her temporary residence on a hill between village and cemetery, she embarks on walks and outings, exploring the banal and the sublime with equal dedication and intensity. Seeing, describing, naming the world around her is her way of redefining her place within it. Written in a rich and poetic style, Grove is an exquisite novel of grief, love and landscapes.

Camille Laurens, Little Dancer Aged Fourteen, translated from French by Willard Wood (Nonfiction/Art/Biography) (Les Fugitives, 2020)

This absorbing, heartfelt work tells the story of the real dancer behind Degas’s now-iconic sculpture, and the struggles of late nineteenth-century bohemian life of Paris.

This absorbing, heartfelt work tells the story of the real dancer behind Degas’s now-iconic sculpture, and the struggles of late nineteenth-century bohemian life of Paris.

Famous throughout the world, how many know her name? Admired in paintings in Washington, Paris, London and New York but where is she buried? We know her age, 14, and the grueling work she did, at an age when children today are in school. In the 1880s, she danced as a “little rat” at the Paris Opera; what is a dream for girls now wasn’t a dream then. Fired after years of hard work when the director had had enough of her repeated absences, she had been working another job as the few pennies the Opera paid weren’t enough to keep her family fed. A model, she posed for painters or sculptors, among them Edgar Degas.

Drawing on a wealth of historical material and her own love of ballet and personal experience of loss, Camille Laurens presents a compelling, compassionate portrait of Marie van Goethem and the world of the artists’ models themselves, often overlooked in the history of art.

Scholastique Mukasonga, Our Lady of the Nile, translated from French by Melanie Mauthner (Fiction/Rwanda) (Daunt Books Publishing, 2021)

Parents send their daughters to Our Lady of the Nile to be moulded into respectable citizens, to protect them from the dangers of the outside world. The young ladies are expected to learn, eat, and live together, presided over by the colonial white nuns.

Parents send their daughters to Our Lady of the Nile to be moulded into respectable citizens, to protect them from the dangers of the outside world. The young ladies are expected to learn, eat, and live together, presided over by the colonial white nuns.

It is 15 years prior to the 1994 Rwandan genocide and a quota permits only two Tutsi students for every twenty pupils. As Gloriosa, the school’s Hutu queen bee, tries on her parents’ preconceptions and prejudices, Veronica and Virginia, both Tutsis, are determined to find a place for themselves and their history. In the struggle for power and acceptance, the lycée is transformed into a microcosm of the country’s mounting racial tensions and violence. During the interminable rainy season, everything slowly unfolds behind the school’s closed doors: friendship, curiosity, fear, deceit, and persecution.

A landmark novel about a country divided and a society hurtling towards horror. In gorgeous and devastating prose, Mukasonga captures the dreams, ambitions and prejudices of young women growing up as their country falls apart.

Duanwad Pimwana, Arid Dreams, translated from Thai by Mui Poopoksakul (short stories) (Tilted Axis Press, 2020)

In 13 stories that investigate ordinary and working-class Thailand, characters aspire for more but remain suspended in routine. They bide their time, waiting for an extraordinary event to end their stasis. A politician’s wife imagines her life had her husband’s accident been fatal, a man on death row requests that a friend clear up a misunderstanding with a prostitute, and an elevator attendant feels himself wasting away while trapped, immobile, at his station all day.

In 13 stories that investigate ordinary and working-class Thailand, characters aspire for more but remain suspended in routine. They bide their time, waiting for an extraordinary event to end their stasis. A politician’s wife imagines her life had her husband’s accident been fatal, a man on death row requests that a friend clear up a misunderstanding with a prostitute, and an elevator attendant feels himself wasting away while trapped, immobile, at his station all day.

With curious wit, this collection offers revelatory insight and subtle critique, exploring class, gender, and disenchantment in a changing country.

Olga Ravn, The Employees, translated from Danish by Martin Aitken (Science Fiction) (Lolli Editions, 2020)

A workplace novel of the 22nd century. The near-distant future. Millions of kilometres from Earth.

A workplace novel of the 22nd century. The near-distant future. Millions of kilometres from Earth.

The crew of the Six-Thousand ship consists of those who were born, and those who were created. Those who will die, and those who will not. When the ship takes on strange objects from the planet New Discovery, the crew is perplexed to find itself becoming attached to them, and human and humanoid employees alike find themselves longing for the same things: warmth and intimacy. Loved ones who have passed. Our shared, far-away Earth, now only persists in memory.

Gradually, the crew members come to see themselves in a new light, each employee is compelled to ask themselves whether their work can carry on as before – what it means to be truly alive.

Structured as a series of witness statements compiled by a workplace commission, Ravn’s crackling prose is as chilling as it is moving, as exhilarating as it is foreboding. Wracked by all kinds of longing, The Employees probes what it means to be human, emotionally and ontologically, while delivering an overdue critique of a life governed by work and the logic of productivity.

Judith Schalansky, An Inventory of Losses, translated from German by Jackie Smith (Essays/Experimental) MacLehose Press, 2020)

A dazzling cabinet of curiosities from one of Europe’s most acclaimed and inventive writers.

A dazzling cabinet of curiosities from one of Europe’s most acclaimed and inventive writers.

Each of the pieces, following the conventions of a different genre, considers something that is irretrievably lost to the world, including the paradisal pacific island of Tuanaki, the Caspian Tiger, the Villa Sacchetti in Rome, Sappho’s love poems, Greta Garbo’s fading beauty, a painting by Caspar David Friedrich, and the former East Germany’s Palace of the Republic.

As a child of the former East Germany, the dominant emotion in Schalansky’s work is “loss” and its aftermath, in an engaging mixture of intellectual curiosity, with a down-to-earth grasp of life’s pitiless vitality, ironic humour, stylistic elegance and intensity of feeling that combine to make this one of the most original and beautifully designed books to be published in 2020.

Adania Shibli, Minor Detail, translated from Arabic by Elisabeth Jaquette (Fiction/Palestine) (Fitzcarraldo Editions, 2020)

Minor Detail begins during the summer of 1949, one year after the war that the Palestinians mourn as the Nakba – the catastrophe that led to the displacement and expulsion of more than 700,000 people – and the Israelis celebrate as the War of Independence. Israeli soldiers capture and rape a young Palestinian woman, and kill and bury her in the sand. Many years later, a woman in Ramallah becomes fascinated to the point of obsession with this ‘minor detail’ of history. A haunting meditation on war, violence and memory, Minor Detail cuts to the heart of the Palestinian experience of dispossession, life under occupation, and the persistent difficulty of piecing together a narrative in the face of ongoing erasure and disempowerment.

Minor Detail begins during the summer of 1949, one year after the war that the Palestinians mourn as the Nakba – the catastrophe that led to the displacement and expulsion of more than 700,000 people – and the Israelis celebrate as the War of Independence. Israeli soldiers capture and rape a young Palestinian woman, and kill and bury her in the sand. Many years later, a woman in Ramallah becomes fascinated to the point of obsession with this ‘minor detail’ of history. A haunting meditation on war, violence and memory, Minor Detail cuts to the heart of the Palestinian experience of dispossession, life under occupation, and the persistent difficulty of piecing together a narrative in the face of ongoing erasure and disempowerment.

Małgorzata Szejnert, Ellis Island: A People’s History, translated from Polish by Sean Gasper Bye (Nonfiction/History) (Scribe UK, 2020)

A landmark work of history that brings voices of the past vividly to life, transforming our understanding of the immigrant experience.

A landmark work of history that brings voices of the past vividly to life, transforming our understanding of the immigrant experience.

Whilst living in New York, journalist Małgorzata Szejnert would gaze out from lower Manhattan at Ellis Island, a dark outline on the horizon. How many stories did this tiny patch of land hold? How many people had joyfully embarked on a new life there — or known the despair of being turned away? How many were held there against their will?

Ellis Island draws on unpublished testimonies, memoirs and correspondence from internees and immigrants, including Russians, Italians, Jews, Japanese, Germans, and Poles, along with commissioners, interpreters, doctors, and nurses — all of whom knew they were taking part in a tremendous historical phenomenon.

It tells many stories of the island, from Annie Moore, the Irishwoman who was the first to be processed there, to the diaries of Fiorello La Guardia, who worked at the station before going on to become one of New York City’s mayors, to depicting the ordeal the island went through on 9/11. At the book’s core are letters recovered from the Russian State Archive, a heartrending trove of correspondence from migrants to their loved ones back home. Their letters never reached their destination: they were confiscated by intelligence services and remained largely unseen.

Far from the open-door policy of myth, we see that deportations from Ellis Island were often based on pseudo-scientific ideas about race, gender, and disability. Sometimes families were broken up, and new arrivals were held in detention at the Island for days, weeks, or months under quarantine. Indeed the island compound spent longer as an internment camp than a migration station.

Today, the island is no less political. In popular culture, it is a romantic symbol of the generations of immigrants that reshaped the US. Its true history reveals that today’s immigration debate has deep roots. Now a master storyteller brings its past to life, illustrated with unique photographs.

Maria Stepanova, In Memory of Memory, translated from Russian by Sasha Dugdale (essay/fiction/memoir/travelogue/historical) (Fitzcarraldo Editions, 2021)

With the death of her aunt, Maria Stepanova is left to sift through an apartment full of faded photographs, old postcards, letters, diaries, and heaps of souvenirs: a withered repository of a century of life in Russia. Carefully reassembled with calm, steady hands, these shards tell the story of how a seemingly ordinary Jewish family somehow managed to survive the myriad persecutions and repressions of the last century.

With the death of her aunt, Maria Stepanova is left to sift through an apartment full of faded photographs, old postcards, letters, diaries, and heaps of souvenirs: a withered repository of a century of life in Russia. Carefully reassembled with calm, steady hands, these shards tell the story of how a seemingly ordinary Jewish family somehow managed to survive the myriad persecutions and repressions of the last century.

In dialogue with writers like Roland Barthes, W. G. Sebald, Susan Sontag and Osip Mandelstam, In Memory of Memory is imbued with rare intellectual curiosity and a wonderfully soft-spoken, poetic voice. Dipping into various forms – essay, fiction, memoir, travelogue and historical documents – Stepanova assembles a vast panorama of ideas and personalities and offers an entirely new and bold exploration of cultural and personal memory.

Maria Stepanova, War of the Beasts and the Animals, translated from Russian by Sasha Dugdale (Poetry/Experimental) (Bloodaxe Books, 2021)

Stepanova is one of Russia’s most innovative and exciting poets and thinkers. Immensely high-profile in Russia, her reputation has lagged behind in the West.

Stepanova is one of Russia’s most innovative and exciting poets and thinkers. Immensely high-profile in Russia, her reputation has lagged behind in the West.

War of the Beasts and the Animals includes recent long poems of conflict ‘Spolia’ and ‘War of the Beasts and Animals’, written during the Donbas conflict, as well as a third long poem ‘The Body Returns’, commemorates the Centenary of WWI. In all three poems Stepanova’s assured and experimental use of form, her modernist appropriation of poetic texts from around the world and her consideration of the way that culture, memory and contemporary life are interwoven make her work pleasurable and relevant.

This collection includes two sequences of poems from her 2015 collection Kireevsky: sequences of ‘weird’ ballads and songs, subtly changed folk and popular songs and poems that combine historical lyricism and a contemporary understanding of the effects of conflict and trauma. Stepanova uses the forms of ballads and songs, but alters them so they almost appear to be refracted in moonlit water. The forms seem recognisable, but the words are fragmented and suggestive, they weave together well-known refrains of songs, familiar images, subtle half-nods to films and music.

Alice Zeniter, The Art of Losing, translated from French by Frank Wynne (Historical Fiction/Algeria) (Picador, 2021)

Naïma has always known her family came from Algeria – until now, that meant little to her. Born and raised in France, her knowledge of that foreign country is limited to what she’s learned from her grandparents’ tiny flat in a crumbling French housing estate: the food cooked for her, the few precious things they brought with them when they fled.

Naïma has always known her family came from Algeria – until now, that meant little to her. Born and raised in France, her knowledge of that foreign country is limited to what she’s learned from her grandparents’ tiny flat in a crumbling French housing estate: the food cooked for her, the few precious things they brought with them when they fled.

Of the past, the family is silent. Why was her grandfather Ali forced to leave? Was he a harki – an Algerian who worked for and supported the French during the Algerian War of Independence? Once a wealthy landowner, how did he become an immigrant scratching a living in France?

Naïma’s father, Hamid, says he remembers nothing. A child when the family left, in France he re-made himself: education was his ticket out of the family home, the key to acceptance into French society. Now, for the first time since they left, one of Ali’s family is going back. Naïma will see Algeria for herself, will ask questions about her family’s history that till now, have had no answers.

Spanning three generations across seventy years, The Art of Losing tells the story of how people carry on in the face of loss: the loss of a country, an identity, a way to speak to your children. It’s a story of colonisation and immigration, and how in some ways, we are a product of the things we’ve left behind.

* * * * *

I haven’t read any of these, though many are familiar, as I have seen them reviewed and discussed. The range of genres is impressive, making it an eclectic selection. I’m interested in The Lady of the Nile, Minor Detail, and Annie Ernaux is an author I’m keen to read, though where to start, as she has seven short memoirs now in English and I keep thinking I ought to read a few in French.

Have you read or heard of any of these titles? Tempted by anything?

Coincidentally, the day I started reading it, I became aware it was one of the five shortlisted novels for the Canadian literary award, the Scotiabank Giller Prize on the same day the winner was to be announced.

Coincidentally, the day I started reading it, I became aware it was one of the five shortlisted novels for the Canadian literary award, the Scotiabank Giller Prize on the same day the winner was to be announced.

As their stories unfold, we also discover the importance of these women’s friendships, both of them have been helped by their best female friend at a turning point in their lives and the mystery gradually unfolds as to what has brought these unexpected allies together.

As their stories unfold, we also discover the importance of these women’s friendships, both of them have been helped by their best female friend at a turning point in their lives and the mystery gradually unfolds as to what has brought these unexpected allies together. Cheluchi Onyemelukwe-Onuobia is a Nigerian-Canadian lawyer, academic and writer.

Cheluchi Onyemelukwe-Onuobia is a Nigerian-Canadian lawyer, academic and writer.

It is 14 years since Jinx’s mother died and the knock on her door by a friend of her mother’s she hasn’t seen since then, initiates this weekend like no other, which will bring back all the emotion, rage, resentment, passion and sorrow that has been pushed down so deep for years.

It is 14 years since Jinx’s mother died and the knock on her door by a friend of her mother’s she hasn’t seen since then, initiates this weekend like no other, which will bring back all the emotion, rage, resentment, passion and sorrow that has been pushed down so deep for years.

Yvvette Edwards is a British East Londoner of Montserratian origin and author of two novels, A Cupboard Full of Coats and The Mother. Her short stories have been published in anthologies including New Daughters of Africa, and broadcast on radio.

Yvvette Edwards is a British East Londoner of Montserratian origin and author of two novels, A Cupboard Full of Coats and The Mother. Her short stories have been published in anthologies including New Daughters of Africa, and broadcast on radio.

Parents send their daughters to Our Lady of the Nile to be moulded into respectable citizens, to protect them from the dangers of the outside world. The young ladies are expected to learn, eat, and live together, presided over by the colonial white nuns.

Parents send their daughters to Our Lady of the Nile to be moulded into respectable citizens, to protect them from the dangers of the outside world. The young ladies are expected to learn, eat, and live together, presided over by the colonial white nuns. A dazzling cabinet of curiosities from one of Europe’s most acclaimed and inventive writers.

A dazzling cabinet of curiosities from one of Europe’s most acclaimed and inventive writers. With the death of her aunt, Maria Stepanova is left to sift through an apartment full of faded photographs, old postcards, letters, diaries, and heaps of souvenirs: a withered repository of a century of life in Russia. Carefully reassembled, these shards tell the story of how a seemingly ordinary Jewish family somehow managed to survive the myriad persecutions and repressions of the last century.

With the death of her aunt, Maria Stepanova is left to sift through an apartment full of faded photographs, old postcards, letters, diaries, and heaps of souvenirs: a withered repository of a century of life in Russia. Carefully reassembled, these shards tell the story of how a seemingly ordinary Jewish family somehow managed to survive the myriad persecutions and repressions of the last century. One of Russia’s most innovative and exciting poets and thinkers, though high-profile in Russia, her reputation has lagged elsewhere.

One of Russia’s most innovative and exciting poets and thinkers, though high-profile in Russia, her reputation has lagged elsewhere. A landmark work of history that brings voices of the past vividly to life, transforming our understanding of the immigrant experience.

A landmark work of history that brings voices of the past vividly to life, transforming our understanding of the immigrant experience. In the fictional Chinese town of Yong’an, human beings live alongside spirits and monsters, some of almost indistinguishable from people.

In the fictional Chinese town of Yong’an, human beings live alongside spirits and monsters, some of almost indistinguishable from people. Naïma has always known her family came from Algeria – until now, that meant little to her. Born and raised in France, her knowledge of that foreign country is limited to what she’s learned from her grandparents’ tiny flat in a crumbling French housing estate: the food cooked for her, the few precious things they brought with them when they fled.

Naïma has always known her family came from Algeria – until now, that meant little to her. Born and raised in France, her knowledge of that foreign country is limited to what she’s learned from her grandparents’ tiny flat in a crumbling French housing estate: the food cooked for her, the few precious things they brought with them when they fled. I enjoyed Lies of Silence, however was completely wound up by his treatment of the character in The Lonely Passion of Judith Hearne, a feeling of indignation in his treatment of the female protagonist that was expounded on by Colm Tóibín who admitted:

I enjoyed Lies of Silence, however was completely wound up by his treatment of the character in The Lonely Passion of Judith Hearne, a feeling of indignation in his treatment of the female protagonist that was expounded on by Colm Tóibín who admitted:

An Immigrant Story

An Immigrant Story

The book is about Theo, a widower and astrophysicist, raising his nine year old son Robin alone, two years after the death of his wife.

The book is about Theo, a widower and astrophysicist, raising his nine year old son Robin alone, two years after the death of his wife.

In post-soviet Georgia, on the outskirts of Tbilisi, on the corner of Kerch St., is an orphanage. Its teachers offer pupils lessons in violence, abuse and neglect. Lela is old enough to leave but has nowhere else to go. She stays and plans for the children’s escape, for the future she hopes to give to Irakli, a young boy in the home. When an American couple visits, offering the prospect of a new life, Lela decides she must do everything she can to give Irakli this chance.

In post-soviet Georgia, on the outskirts of Tbilisi, on the corner of Kerch St., is an orphanage. Its teachers offer pupils lessons in violence, abuse and neglect. Lela is old enough to leave but has nowhere else to go. She stays and plans for the children’s escape, for the future she hopes to give to Irakli, a young boy in the home. When an American couple visits, offering the prospect of a new life, Lela decides she must do everything she can to give Irakli this chance. Annie Ernaux revisits the summer of 1958, spent working as a holiday camp instructor in Normandy, and recounts the first night she spent with a man. When he moves on, she realizes she has submitted her will to his and finds that she is a slave without a master. Now, sixty years later, she finds she can obliterate the intervening years and return to consider this young woman whom she wanted to forget completely. In writing A Girl’s Story, which brings to life her indelible memories of that summer, Ernaux discovers that here was the vital, violent and dolorous origin of her writing life, built out of shame, violence and betrayal.

Annie Ernaux revisits the summer of 1958, spent working as a holiday camp instructor in Normandy, and recounts the first night she spent with a man. When he moves on, she realizes she has submitted her will to his and finds that she is a slave without a master. Now, sixty years later, she finds she can obliterate the intervening years and return to consider this young woman whom she wanted to forget completely. In writing A Girl’s Story, which brings to life her indelible memories of that summer, Ernaux discovers that here was the vital, violent and dolorous origin of her writing life, built out of shame, violence and betrayal. A collection of intimate and explosive essays on literature, life, history, politics and place. Drawing from her 25 years of thinking and writing, the book plots a journey through the works and subjects that have inspired and influenced her.

A collection of intimate and explosive essays on literature, life, history, politics and place. Drawing from her 25 years of thinking and writing, the book plots a journey through the works and subjects that have inspired and influenced her. From the author of the internationally bestselling Strange Weather in Tokyo, a collection of interlinking stories that blend the mundane and the mythical—“fairy tales in the best Brothers Grimm tradition: naif, magical, and frequently veering into the macabre”.

From the author of the internationally bestselling Strange Weather in Tokyo, a collection of interlinking stories that blend the mundane and the mythical—“fairy tales in the best Brothers Grimm tradition: naif, magical, and frequently veering into the macabre”. An unnamed narrator, recently bereaved, travels to Olevano, a small village south-east of Rome. It is winter, and from her temporary residence on a hill between village and cemetery, she embarks on walks and outings, exploring the banal and the sublime with equal dedication and intensity. Seeing, describing, naming the world around her is her way of redefining her place within it. Written in a rich and poetic style, Grove is an exquisite novel of grief, love and landscapes.

An unnamed narrator, recently bereaved, travels to Olevano, a small village south-east of Rome. It is winter, and from her temporary residence on a hill between village and cemetery, she embarks on walks and outings, exploring the banal and the sublime with equal dedication and intensity. Seeing, describing, naming the world around her is her way of redefining her place within it. Written in a rich and poetic style, Grove is an exquisite novel of grief, love and landscapes. This absorbing, heartfelt work tells the story of the real dancer behind Degas’s now-iconic sculpture, and the struggles of late nineteenth-century bohemian life of Paris.

This absorbing, heartfelt work tells the story of the real dancer behind Degas’s now-iconic sculpture, and the struggles of late nineteenth-century bohemian life of Paris. In 13 stories that investigate ordinary and working-class Thailand, characters aspire for more but remain suspended in routine. They bide their time, waiting for an extraordinary event to end their stasis. A politician’s wife imagines her life had her husband’s accident been fatal, a man on death row requests that a friend clear up a misunderstanding with a prostitute, and an elevator attendant feels himself wasting away while trapped, immobile, at his station all day.

In 13 stories that investigate ordinary and working-class Thailand, characters aspire for more but remain suspended in routine. They bide their time, waiting for an extraordinary event to end their stasis. A politician’s wife imagines her life had her husband’s accident been fatal, a man on death row requests that a friend clear up a misunderstanding with a prostitute, and an elevator attendant feels himself wasting away while trapped, immobile, at his station all day. A workplace novel of the 22nd century. The near-distant future. Millions of kilometres from Earth.

A workplace novel of the 22nd century. The near-distant future. Millions of kilometres from Earth. Minor Detail begins during the summer of 1949, one year after the war that the Palestinians mourn as the Nakba – the catastrophe that led to the displacement and expulsion of more than 700,000 people – and the Israelis celebrate as the War of Independence. Israeli soldiers capture and rape a young Palestinian woman, and kill and bury her in the sand. Many years later, a woman in Ramallah becomes fascinated to the point of obsession with this ‘minor detail’ of history. A haunting meditation on war, violence and memory, Minor Detail cuts to the heart of the Palestinian experience of dispossession, life under occupation, and the persistent difficulty of piecing together a narrative in the face of ongoing erasure and disempowerment.

Minor Detail begins during the summer of 1949, one year after the war that the Palestinians mourn as the Nakba – the catastrophe that led to the displacement and expulsion of more than 700,000 people – and the Israelis celebrate as the War of Independence. Israeli soldiers capture and rape a young Palestinian woman, and kill and bury her in the sand. Many years later, a woman in Ramallah becomes fascinated to the point of obsession with this ‘minor detail’ of history. A haunting meditation on war, violence and memory, Minor Detail cuts to the heart of the Palestinian experience of dispossession, life under occupation, and the persistent difficulty of piecing together a narrative in the face of ongoing erasure and disempowerment. The children at school ask about her skin colour and ethnic origin.

The children at school ask about her skin colour and ethnic origin.

Sally Morgan is one of Australia’s best-known Aboriginal artists and writers.

Sally Morgan is one of Australia’s best-known Aboriginal artists and writers. Written in three parts, this award winning novel by Lebanese author Hada Barakat, is composed of a series of six letters written in a stream of consciousness narrative that are interlinked. The letters are read, but not by their intended recipient, found between the pages of a book, dug out of a bin or otherwise encountered. They prompt the finder to write their own letter.

Written in three parts, this award winning novel by Lebanese author Hada Barakat, is composed of a series of six letters written in a stream of consciousness narrative that are interlinked. The letters are read, but not by their intended recipient, found between the pages of a book, dug out of a bin or otherwise encountered. They prompt the finder to write their own letter.

Hoda Barakat was born in Beirut in 1952. She has worked in teaching and journalism and lives in France. She has published six novels, two plays, a book of short stories and a book of memoirs, as well as contributing to books written in French. Her work has been translated into a number of languages.

Hoda Barakat was born in Beirut in 1952. She has worked in teaching and journalism and lives in France. She has published six novels, two plays, a book of short stories and a book of memoirs, as well as contributing to books written in French. Her work has been translated into a number of languages.