Rebecca Solnit writes reflective, thought-provoking essays, which often connect her intellectual curiosity with where she is in her life now. In an earlier work Wanderlust, she ponders the history of walking as a cultural and political experience; facing the unknown, in A Field Guide to Getting Lost; her mother’s Alzheimer’s, regression and how she spent that final year in The Faraway Nearby.

Rebecca Solnit writes reflective, thought-provoking essays, which often connect her intellectual curiosity with where she is in her life now. In an earlier work Wanderlust, she ponders the history of walking as a cultural and political experience; facing the unknown, in A Field Guide to Getting Lost; her mother’s Alzheimer’s, regression and how she spent that final year in The Faraway Nearby.

Now a new collection of essays, the title The Mother of All Questions, from an introductory piece on one of her pet frustrations, that all time irrelevant question that many professional women, whether they are writer’s, politicians or humble employees too often get asked.

But it is the timely and questioning opening essay ‘A Short History on Silence’ that binds the collection together and should be the question being asked. It is an attempt at a history of silence, in particular the silencing of women, the effect of patriarchal power, the culpability of institutions, universities, the court system, the police, even families, their roles in continuing to ensure women’s silence over the continual transgressions of men.

Rebecca Solnit has been writing about this issue for many years, trying to create a public conversation on a subject that many continued to insist was a personal problem – yet another form of silencing.

As she wrote in Wanderlust (2000)

As she wrote in Wanderlust (2000)

“It was the most devastating discovery of my life that I had no real right to life, liberty, and pursuit of happiness out of doors, that the world was full of strangers who seemed to hate me and wished to harm me for no reason other than my gender, that sex so readily became violence, and that hardly anyone else considered it a public issue rather than a private problem.”

She makes a distinction between silence being that which is imposed and quiet being that which is sought.

What is left unsaid because serenity and introspection are sought is as different from what is not said because the threats are high or the barriers are great as swimming is from drowning. Quiet is to noise as silence is to communication. The quiet of the listener makes room for the speech of others, like the quiet of the reader taking in the words on the page…Silence is what allows people to suffer without recourse, what allows hypocrisies and lies to grow and flourish, crimes to go unpunished. If our voices are essential aspects of our humanity, to be rendered voiceless is to be dehumanized or excluded from one’s humanity. And the history of silence is central to women’s history’

The list of who has been silenced goes right back to the dawn of literature, it goes back millennia, classics scholar Mary Beard noted that silencing women begins almost as soon as Western literature does, in the Odyssey, with Telemachus telling his mother to shut up.

It continues through the years with the woman’s exclusion from education, from the right to vote, to making or being acknowledged for making scientific discoveries to campus rape and the introduction of sexual harassment guidelines as law and the unleashing of stories and the wave of voices coming out of silence that sharing on social media has spawned, generating a fiercely lively and unprecedented conversation.

80 Books No Woman Should Read is her response to a list published by Esquire magazine of a list they created of 80 books every man should read, a list of books, seventy-nine of which were written by men, with one by Flannery O’Connor. It speaks of the reader’s tendency to identify with the protagonist, only the books she mentions from this list that she has read, she often identifies, not with the protagonist but with the woman, noticing that some books are instructions on why women are dirt or hardly exist at all except as accessories or are inherently evil and empty.

Not surprisingly, her essay (first published at Lithub.com) elicited a significant online response, prompting a reply from Esquire, admitting they’d messed up, saying their article had rightfully been called out for its lack of diversity, and proactively inviting eight female literary powerhouses, from Michiko Kakutani to Anna Holmes to Roxanne Gay, to help them create a new list. You can see the list here.

And in the essay In Men Explain Lolita to Me she expounds further on empathy:

‘This paying attention is the foundational act of empathy, of listening, of seeing, of imagining experiences other than one’s own, of getting out of the boundaries of one’s own experience. There’s a currently popular argument that books help us feel empathy, but if they do so they do it by helping us imagine that we are people we are not. Or to go deeper within ourselves, to be more aware of what it means to be heartbroken, or ill, or ninety-six, or completely lost. Not just versions of our self rendered awesome and eternally justified and always right, living in a world in which other people only exist to help reinforce our magnificence, though those kinds of books and comic books and movies exist in abundance to cater to the male imagination. Which is a reminder that literature and art can also help us fail at empathy if it sequesters in the Boring Old Fortress of Magnificent Me.’

I haven’t read Men Explain Things to Me, although I heard Rebecca Solnit speak about the leading and infamous anecdote it retells when I went to listen to her at the Royal Festival Hall in London.

I haven’t read Men Explain Things to Me, although I heard Rebecca Solnit speak about the leading and infamous anecdote it retells when I went to listen to her at the Royal Festival Hall in London.

That talk coincided with the publication of The Faraway Nearby (link to review) the book that traverses her uneasy relationship with her mother and how the approach of death forces her to contemplate it, how it may have shaped her. I liked the book, but I loved listening to the author in person, she has such an engaging presence, is a captivating speaker, a performer of the reflective and spontaneous.

The Mother of All Questions is a culmination of Solnit’s and many women’s frustrations in the world today, where being a woman living in a patriarchal culture, no matter which part of the world, brings challenges that must reach a breaking point. It is a conversation that is happening everywhere that hopefully will bring change for the better, as many voices come together in solidarity. It is an acknowledgement both of how far we have come and how much we have still to do, to change the culture of silence we have inhabited for too long, to safely be ourselves.

I highly recommend picking up one of her works, if you haven’t yet read her.

The opening story is a mix of reportage and a retelling of the story of Mangilaluk Bernard Andreason, who when he was 11 years old, slipped out of the Inuvik residential boarding school he’d been sent to, along with two friends Jack and Dennis, to avoid being punished for stealing a pack of cigarettes, and spotting newly hung power lines, decided to follow them home to Tuktoyaktuk.

The opening story is a mix of reportage and a retelling of the story of Mangilaluk Bernard Andreason, who when he was 11 years old, slipped out of the Inuvik residential boarding school he’d been sent to, along with two friends Jack and Dennis, to avoid being punished for stealing a pack of cigarettes, and spotting newly hung power lines, decided to follow them home to Tuktoyaktuk.

With it’s 111 vibes or spiritual practices, it’s designed not to be read in one sitting, but daily or randomly. I found often that the vibe for the day was often something that really resonated with my day, it’s also like an energising, elevating pick me up or start to the day, it sets the tone for the rest of the day.

With it’s 111 vibes or spiritual practices, it’s designed not to be read in one sitting, but daily or randomly. I found often that the vibe for the day was often something that really resonated with my day, it’s also like an energising, elevating pick me up or start to the day, it sets the tone for the rest of the day.

The second volume of essays by Kathleen Jamie that I’ve read, more encounters with birds on lonely, windswept islands that have long been abandoned by humans, though traces remain of their earlier occupation.

The second volume of essays by Kathleen Jamie that I’ve read, more encounters with birds on lonely, windswept islands that have long been abandoned by humans, though traces remain of their earlier occupation.

The Hvalsalen

The Hvalsalen

If you have achieved things because you were capable, but they left you feeling unfulfilled, if you’ve ever felt as though there is something else you are supposed to be doing in this life but didn’t know exactly what, if you enjoy the feeling of being guided by your intuition when it proves to be spot on, if you sense that we are more than just a physical body here for one lifetime, then this book will appeal to you.

If you have achieved things because you were capable, but they left you feeling unfulfilled, if you’ve ever felt as though there is something else you are supposed to be doing in this life but didn’t know exactly what, if you enjoy the feeling of being guided by your intuition when it proves to be spot on, if you sense that we are more than just a physical body here for one lifetime, then this book will appeal to you.

I’m definitely going to read her next book, Rise Sister Rise: A Guide to Unleashing the Wise, Wild Woman Within which focuses more on the rise of the feminine, on those aspects of women that have been long suppressed by the patriarchal model we have lived under for eons and how the world is beginning to change as more women connect and together begin to heal those ancient wounds, to value once more that innate wisdom of the feminine.

I’m definitely going to read her next book, Rise Sister Rise: A Guide to Unleashing the Wise, Wild Woman Within which focuses more on the rise of the feminine, on those aspects of women that have been long suppressed by the patriarchal model we have lived under for eons and how the world is beginning to change as more women connect and together begin to heal those ancient wounds, to value once more that innate wisdom of the feminine. Before I went to visit and spend two months in Bethlehem, Palestine some years ago, I wanted to read something about the history of the area, not a religious book, but something historical that went beyond the recent familiar history since the British abandoned those residing in these lands to their fate. I wanted to understand the wider context of how people came to be living here and what they’d had to endure to survive.

Before I went to visit and spend two months in Bethlehem, Palestine some years ago, I wanted to read something about the history of the area, not a religious book, but something historical that went beyond the recent familiar history since the British abandoned those residing in these lands to their fate. I wanted to understand the wider context of how people came to be living here and what they’d had to endure to survive. Recently I was recommended a couple more Karen Armstrong books

Recently I was recommended a couple more Karen Armstrong books

which is a mild example of the kind of comportment (at different levels of societal power clearly) that nevertheless can lead to disharmony, conflict, war even, for if there is a conclusion to what Karen Armstrong has learned, it is a lesson she gifts to her readers, known as Hillel’s Golden Rule that all great leaders have taught, Confucius proclaimed it 500 years before him, Buddha and Jesus taught it, it is the bedrock of the Koran:

which is a mild example of the kind of comportment (at different levels of societal power clearly) that nevertheless can lead to disharmony, conflict, war even, for if there is a conclusion to what Karen Armstrong has learned, it is a lesson she gifts to her readers, known as Hillel’s Golden Rule that all great leaders have taught, Confucius proclaimed it 500 years before him, Buddha and Jesus taught it, it is the bedrock of the Koran:

That transition she made and the mentoring she received became the subject of her first book

That transition she made and the mentoring she received became the subject of her first book  In Worthy, Boost Your Self-Worth to Grow Your Net Worth, she takes the jump a step further and analyses what might be behind the reluctance, or resistance as she likes to call it, to change. She tells the story behind the story of her own life, of how she rarely spent money on herself, but often on her husband because she was trying to make him happy. Through coaching, she was able to have greater awareness of her own patterns and see how she was getting in her own way of achieving what she wanted.

In Worthy, Boost Your Self-Worth to Grow Your Net Worth, she takes the jump a step further and analyses what might be behind the reluctance, or resistance as she likes to call it, to change. She tells the story behind the story of her own life, of how she rarely spent money on herself, but often on her husband because she was trying to make him happy. Through coaching, she was able to have greater awareness of her own patterns and see how she was getting in her own way of achieving what she wanted. The book moves further on, into defining what you want most and how to move from excuses to action, to taking back your power, taking responsibility, practising self-trust and self-respect.

The book moves further on, into defining what you want most and how to move from excuses to action, to taking back your power, taking responsibility, practising self-trust and self-respect.

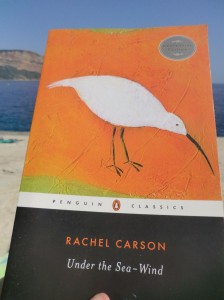

And though I enjoyed Henry Beston’s book considerably, Carson’s book for me left a greater impression, for who could not forget being made to see life through the eyes of the very creatures Henry Beston observes. Carson chose to narrate the three parts of her book from the point of view of a sanderling (bird), a mackerel, and a migrating eel. If you haven’t read it and loved this book, I am sure you will enjoy and appreciate Rachel Carson’s personal favourite of all the books she wrote, it is the perfect companion to The Outermost House.

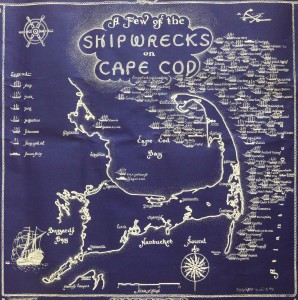

And though I enjoyed Henry Beston’s book considerably, Carson’s book for me left a greater impression, for who could not forget being made to see life through the eyes of the very creatures Henry Beston observes. Carson chose to narrate the three parts of her book from the point of view of a sanderling (bird), a mackerel, and a migrating eel. If you haven’t read it and loved this book, I am sure you will enjoy and appreciate Rachel Carson’s personal favourite of all the books she wrote, it is the perfect companion to The Outermost House. It was the late 1920’s and no doubt a year like any other, with its share of wrecks, disasters. The pragmatic attitudes of the locals, as likely to come to the rescue and do anything to help, as they are to salvage what is left, not always understood by the families of victims of the many shipwrecks.

It was the late 1920’s and no doubt a year like any other, with its share of wrecks, disasters. The pragmatic attitudes of the locals, as likely to come to the rescue and do anything to help, as they are to salvage what is left, not always understood by the families of victims of the many shipwrecks.

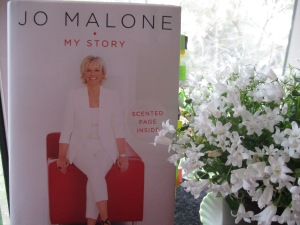

But Jo Malone the girl, wasn’t born into luxury. She was an ordinary girl raised in a family that struggled a bit on the good days, and a lot on the bad days, which were often brought on by her doting father’s gambling inclinations, her mother’s over-spending habit and the pressure to work long hours to keep the family afloat.

But Jo Malone the girl, wasn’t born into luxury. She was an ordinary girl raised in a family that struggled a bit on the good days, and a lot on the bad days, which were often brought on by her doting father’s gambling inclinations, her mother’s over-spending habit and the pressure to work long hours to keep the family afloat. When she really began to play around with fragrance, demand began to rise more than she could cope with, and Gary suggested they embrace the business, move it to its own premise and open a shop. Her business was beginning to overwhelm their living condition, he recognised the potential and offered to commit himself wholeheartedly it. That would be the beginning of Jo Malone, her signature brand.

When she really began to play around with fragrance, demand began to rise more than she could cope with, and Gary suggested they embrace the business, move it to its own premise and open a shop. Her business was beginning to overwhelm their living condition, he recognised the potential and offered to commit himself wholeheartedly it. That would be the beginning of Jo Malone, her signature brand. From there, a whirlwind of events follow and she will partner up with a perfume house in Paris, turning her instinct into a viable, enduring product. She tried to put into words her creative process and it is fascinating when she does, for it is something that can’t be copied or cloned, it is an insight into the pure magic of creativity, of how she uses image, colour and experience to create a scent.

From there, a whirlwind of events follow and she will partner up with a perfume house in Paris, turning her instinct into a viable, enduring product. She tried to put into words her creative process and it is fascinating when she does, for it is something that can’t be copied or cloned, it is an insight into the pure magic of creativity, of how she uses image, colour and experience to create a scent.

I absolutely loved this book, from it’s at times heartbreaking accounts of struggle in childhood, to the discovery of her passion, the development of her creativity and the strong work ethic that carried her forward, to finding the perfect mate and the journey they would go on together.

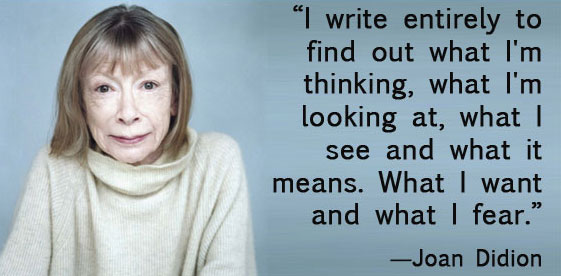

I absolutely loved this book, from it’s at times heartbreaking accounts of struggle in childhood, to the discovery of her passion, the development of her creativity and the strong work ethic that carried her forward, to finding the perfect mate and the journey they would go on together. Written as a reflection on the death of her daughter at 39 years of age, the book begins as Didion thinks back to her daughter’s wedding seven years earlier, which then triggers other memories of her childhood, of family moments, of people and places, numerous hotels they have frequented.

Written as a reflection on the death of her daughter at 39 years of age, the book begins as Didion thinks back to her daughter’s wedding seven years earlier, which then triggers other memories of her childhood, of family moments, of people and places, numerous hotels they have frequented. Although the main theme of the book is her daughter’s premature death, nowhere does she analyse or obsess about what actually happened in the way we vividly remember she did about her husband in My Year of Magical Thinking. Rather, the book appears to be as much an acknowledgement of her own ageing and decline, recognising and facing up to her own ‘frailty’, her obsession with her own health scares, recounting every little malfunction or symptom of a thing that never shows up on any of the numerous scans or tests she has. It is as if she writes her own denouement, to a death that never arrives, as the multitude and thoroughness of all the tests she has show how very much alive and in relative good health she is, despite herself.

Although the main theme of the book is her daughter’s premature death, nowhere does she analyse or obsess about what actually happened in the way we vividly remember she did about her husband in My Year of Magical Thinking. Rather, the book appears to be as much an acknowledgement of her own ageing and decline, recognising and facing up to her own ‘frailty’, her obsession with her own health scares, recounting every little malfunction or symptom of a thing that never shows up on any of the numerous scans or tests she has. It is as if she writes her own denouement, to a death that never arrives, as the multitude and thoroughness of all the tests she has show how very much alive and in relative good health she is, despite herself.