Yesterday I shared my Top 9 Fiction Reads for 2025 along with the One Outstanding Read of 2025 and the runner up. So no surprise to see them here on my best non-fiction of 2025, as the first two titles mentioned here were my two outstanding reads of 2025.

In nonfiction, I like a really good memoir that shares more than just the personal experience, like a good nature writing memoir will increase knowledge of an aspect of nature and share something of a life that is also uplevelling in some way.

Top Non-Fiction

Mother Mary Comes to Me by Arundhati Roy (India)

– This was my Outstanding Read of 2025 and a book that takes a while to process, because these strong women it features, Arundhati Roy and her mother Mary Roy, have achieved incredible feats at a high cost to their basic humanity. They have both lived through situations that required them to fight back, they have lived in close proximity to and been decimated by cruelty and lifted up by personal achievement; they have been revered by an entourage and yet rarely found peace in their relationship to each other or in other close relationships. Intimate and inspirational.

The transparency and honesty with which Arundhati writes, as she walks the reader through childhood in Kerala, early adulthood in Delhi, through a dogged determination to live according to her own values making her both friends and enemies, and through it all that magnetising effect of the mother. Toxic bond or filial loyalty, I’m not entirely sure, but she chose to publish this work, one thinks respectfully, after the ruthless matriarch of steely perseverance let go of her last breath.

“I think I had a cool seraph watching over me. Especially each time I was at a crossroads and had to make a decision. My education, the class I came from, and, above all, the fact that I spoke English protected me and gave me options that millions of others did not have. Those were gifts bestowed on me by Mrs Roy. At no point, no matter how untenable my circumstance, did I ever forget that.”

Somebody is Walking On Your Grave: My Cemetery Journeys by Mariana Enriquez (Argentina) tr. Megan McDowell (Spanish)

– My runner up book for Outstanding Read of 2025 in part because I couldn’t stop telling people about the many different things I learned from reading this book. A memoir-like collection of essays, this really is like super-alternative, armchair travel, where you get to voyage briefly through 13 countries with an experienced, gothic guide to an underworld of 21 cemeteries.

However, the focus isn’t just on the visit, you’re going to be there for a few days, so you’ll get to learn from the highly observant, well researched, perspective of an Argentinian writer (known for unconventional and sociopolitical stories of the macabre) about various cultures, odd behaviours and aspirations of various eras, in how humans have treated those they have revered, once passed. From Genoa to Prague, to Highgate to the Paris catacombs, from Rottnest Island in Australia to Bonaventure in Savannah, from Havana, Cuba to Peru, Mexico, Chile and Argentina, she uses cemeteries to reflect on history, culture, memory, and her own personal life. Outstanding!

Reading Edgar Allen Poe – and then with the years, I learned that also cemeteries have a lot to say about life, about the history of the people. And then Argentina in the ’70s, the decade where I was born, had a dictatorship that made a lot of bodies disappear. Therefore, there’s a generation of people that were killed by the government, and they don’t have a grave.

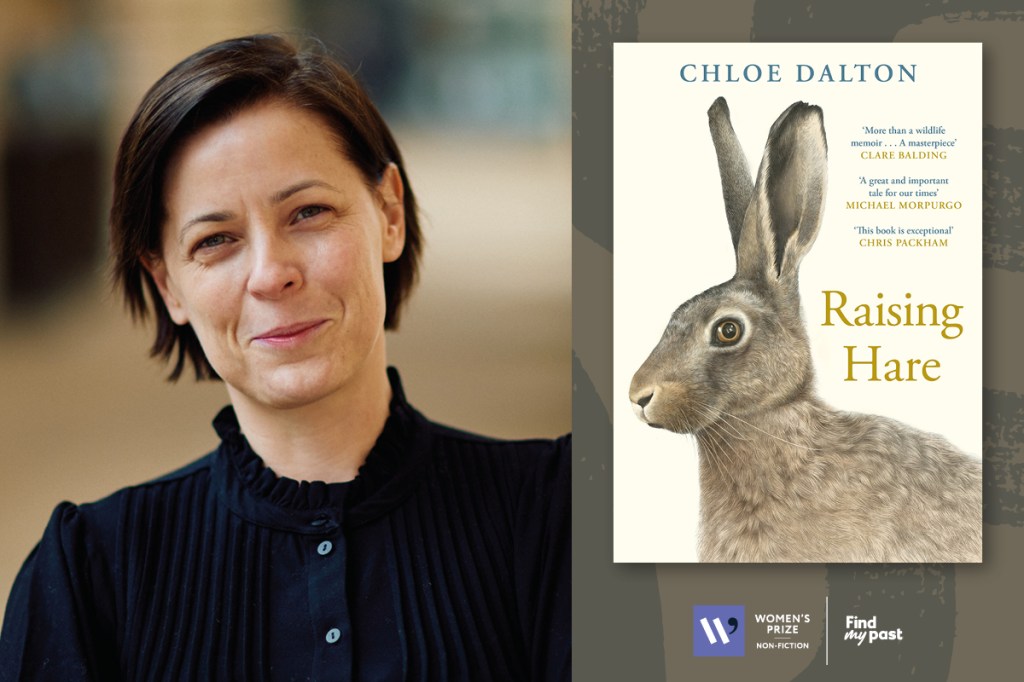

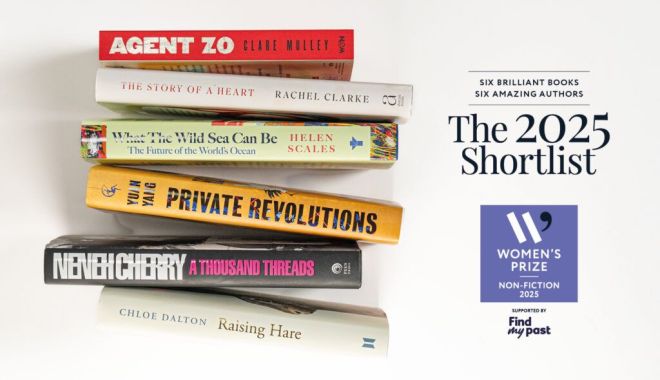

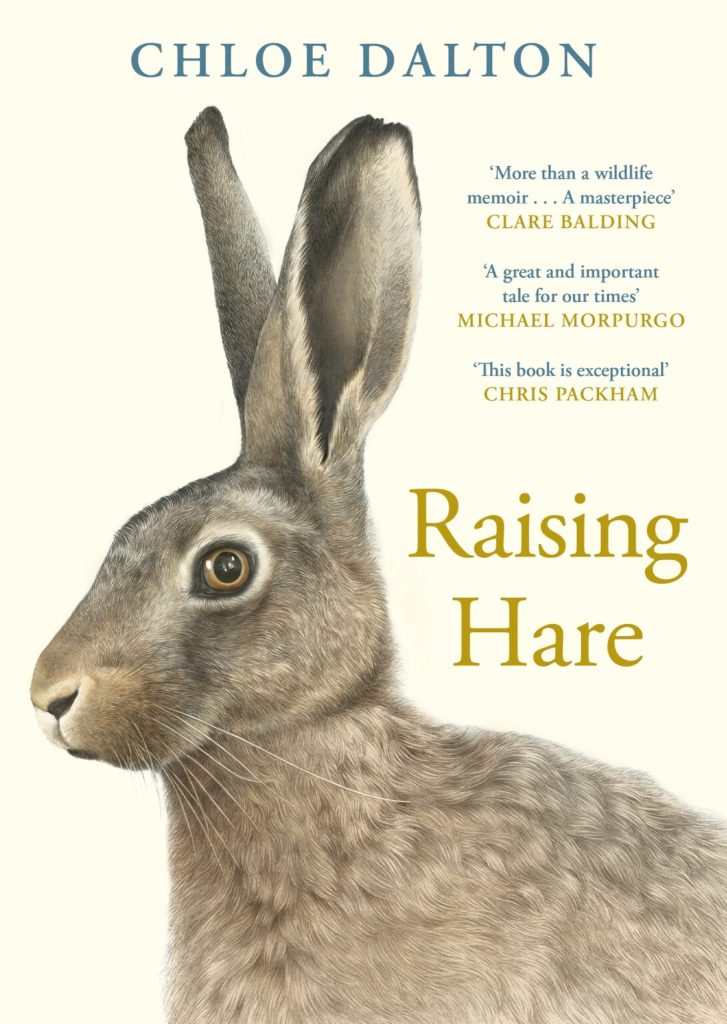

Raising Hare by Chloe Dalton (UK)

– Shortlisted for the Women’s Prize for Nonfiction, I became aware of this title early in the year but waited till the end having read enough reviews to be convinced it was going to be for me. Chloe Dalton hears a bark, stumbles across a leveret and wants to ignore it, but can’t and then lacking knowledge becomes something of an expert on hares and how to care for one, going deep into library archives and reading obscure, ancient texts as well as modern informative ones.

She bonds with the hare but facilitates it return to the wild and then turns her daytime political expertise sights on an outdated policy – Hares are the only game species which are not protected by a ‘close season’ in England and Wales: a period of the year during which they cannot be shot and killed – which I was pleased to read just yesterday, an article in the Guardian Saturday 20 Dec 2025 – Shooting hares in England to be banned for most of the year in sweeping changes to animal welfare law about to be announced in the UK. The new close season will ban hare hunting during the breeding months of February to October to protect mothers and the young.

I pondered the concept of ‘owning’ a living creature in any context. Interaction with animals nurtures the loving, empathetic, compassionate aspects of human nature. It taps into a primordial reverence towards the living world and a sense of the commonality and connectedness across species. It is a gateway, as I was discovering, into a state of greater respect for nature and the environment as a whole. We all too easily subordinate animals to our will, constraining or confining them to suit our purposes, needs and lifestyles.

Is A River Alive? by Robert Macfarlane (UK)

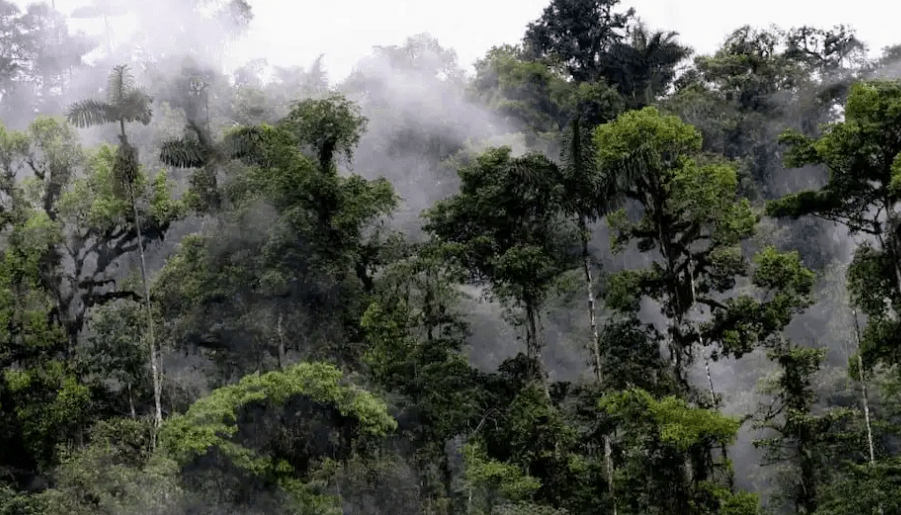

– Another travelling memoir with nature and the environment at the forefront of his journeying, Robert Macfarlane is well known for his mapping of the Old Ways of the ancients, writing about landscapes as living, abundant, storied places and how humans interact with them. So he is very aware of how aspects of nature, such as rivers and streams are being compromised and endangered and killed by humanity, thus he sets out on these three journeys to understand his question, Is a River Alive?

He travels to a cloud-forest in Ecuador with a team of people all looking at nature from different perspectives, a fungi expert, a musician and a ‘Rights of Nature’ lawyer; then to India to find the source of its three rivers with a passionate teacher and advocate for waterways and finally to northern Canada to kayak down a river under threat from corporations wanting to dam it.

Ultimately, beyond his initial question, to which his young son gave him the answer before he even left home, he explores the idea and begins to see for himself, rivers and forests as moral and sentient beings rather than resources to be owned and exploited, shifting from a perspective of ownership to one of responsibility for their guardianship. If we begin to see rivers and the natural world as part of our shared way of living and protect them, we might live more simple and healthy lives.

Spinster, Making a Life of One’s Own by Kate Bolick (US)

– Not one I reviewed, but I came across this memoir while doing genealogical research. I discovered a female ancestor named Mary Stoyle, born in 1791 in Zeal Monachorum, Devon who had five children and on all the baptism certificates she was always the sole parent named. In the census registers, she was Head of Household.

Clearly a man contributed to the conception of her children, but equally it appears he was not part of her household. That made me curious about her Profession and initially under the heading Quality, Trade or Profession, in 1816 when her son George was born, it was listed as Spinster. When Joseph was born in 1831, her Profession had changed to Weaver, which suggested she was financially independent. Women worked at Spinning because it could be done at home, fitted around childcare, and required little capital. Weaving required greater technical skill. Mary was almost certainly a self-supporting handloom weaver, working from home, producing woollen cloth for the local / regional rural economy.

I wondered if anyone had looked into these non-married women from the early 1800’s, as I discovered it was more common than we might think, and that these matriarchs were well respected. So I read Kate Bolick’s book which was a little more modern than what I was looking for, (and focused on but equally fascinating as she explored a number of renowned women from the last century who had tried to live a life without marriage or children in order to pursue some other objective, creative or career.

She looked into the lives of American script writer and columnist Neith Boyce, Irish essayist Maeve Brennan, American social visionary Charlotte Perkins Gilman, poet Edna St. Vincent Millay, and novelist Edith Wharton. Some of these women did marry, but all of them sought ways to escape the traditional expectations of that contract to pursue their own personal ambitions. While it didn’t really help me with my own questions about Mary Stoyle, it was fascinating to read about these women and some of the changing statistics over time, in particular to learn that the institution of marriage was less prominent in the 18th century and reached its peak in the mid 20th century.

Special Mentions, Spiritual Well-Being Top Ups

I read a few books this year that come under the heading of spiritual well-being and two that were particularly good were Rebecca Campbell’s Your Soul Had a Dream, Your Life Is It regarding the cycle of transitions, of resonance and discernment, understanding grief, loss, separation, change. The benefit of going within, of being our own best support, to heal, grow and transmute feeling(s) into the next version of ourselves. To align more with soul purpose, tapping into our inner guidance system. Nothing really new, just good reminders to keep up the practice (s). I’ve read all her books, they’re good to dip in and out of.

The other one I read and listened to was Spirit Hacking (2019) by Shaman Durek, I particularly enjoy his Ancient Wisdom Today podcast pep talks while on a 5 km walk. He is spiritually and intellectually knowledgeable, very direct, often funny, he calls things out, and is deeply encouraging. He comes from a heart-centred background of immersion in Buddhist and Shamanic Philosophy, basically that your thoughts create your reality and the regular checking of what kind of energy you are bringing when responding to challenges and triggers, he gives great examples from personal experiences and admits to his own flaws. He comes to all this with an attitude that may be challenging to some, but I find him interesting to observe, listen to and learn from, filtering out what is useful or not.

* * * * * *

If you’ve read any of these non-fiction titles, or have another favourite for 2025, share them with us in the comments below.

Victoria Bennett was born in Oxfordshire in 1971. A poet and author, her writing has previously received a Northern Debut Award, a Northern Promise Award, the Andrew Waterhouse Award, and has been longlisted for the Penguin WriteNow programme and the inaugural Nan Shepherd Prize for under-represented voices.

Victoria Bennett was born in Oxfordshire in 1971. A poet and author, her writing has previously received a Northern Debut Award, a Northern Promise Award, the Andrew Waterhouse Award, and has been longlisted for the Penguin WriteNow programme and the inaugural Nan Shepherd Prize for under-represented voices. Thin Places is something of an enigma, when I bought it, I thought it was in the nature writing genre, the inside cover calls it a mix of memoir, history and nature writing – such a simplistic description of the reading experience, which for me was something else.

Thin Places is something of an enigma, when I bought it, I thought it was in the nature writing genre, the inside cover calls it a mix of memoir, history and nature writing – such a simplistic description of the reading experience, which for me was something else.

1.

1.  2.

2.  3.

3.  4.

4.  5. Braiding Sweetgrass by Robin Wall Kimmerer (2013) (Creative Non Fiction) (US) – In this remarkable collection of 32 essays, organised into 5 sections that follow the life cycle of sweetgrass, we learn about the philosophy of nature from the perspective of Native American Indigenous Wisdom, shared by a woman of native origin who is a scientist, botanist, teacher, mother.

5. Braiding Sweetgrass by Robin Wall Kimmerer (2013) (Creative Non Fiction) (US) – In this remarkable collection of 32 essays, organised into 5 sections that follow the life cycle of sweetgrass, we learn about the philosophy of nature from the perspective of Native American Indigenous Wisdom, shared by a woman of native origin who is a scientist, botanist, teacher, mother. 6.

6.  7.

7.  8.

8.  9.

9.  10.

10.  This year I found inspiration from two of my favourites in this field, and two new authors, all of them coming from renowned publisher

This year I found inspiration from two of my favourites in this field, and two new authors, all of them coming from renowned publisher

Another new author I picked up this year was Claire Stone and her book

Another new author I picked up this year was Claire Stone and her book  Finally,

Finally,