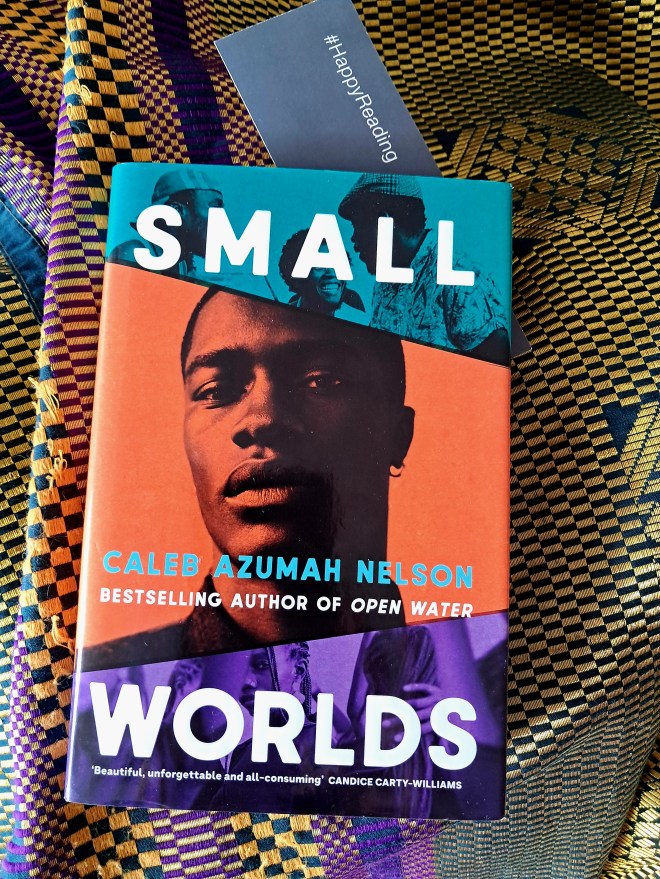

What a brilliant novel this was. I loved it.

It might even be my Outstanding Read of 2025.

A meandering story-line, spanning 3 years, the introspective excavating of a young British-Ghanaian man’s soul and the situations he will encounter and confront, as he matures and grows into a version of himself that he likes.

I highlighted SO many passages.

Moments of Bliss, Small Worlds

Small worlds describes the way Stephen has learned to see things. It is his way of identifying and capturing certain moments, especially the loving, the poignant, the fleeting, the good.

A coming-of-age story set mostly in Peckham, London, it follows Stephen as he navigates the period in his life when he is separating from friends and his parents, from all that he knows. Simultaneously, he is moving from letting things happen to him and suffering, towards sitting with what is, reflecting, rejecting, embracing, understanding. A journey the evolves over three years.

the beats, the rhythm, the soul – A trio

Introspective and sensitive, music plays a large role in his mood, his management of his emotions, his friendships and the collective memory of Ghana, a country he is connected to but did not grow up in, a place that separates him from his family as much as it is a part of them all.

The novel is set over three years, written in three parts, like a jazz trio of piano, bass and drummer.

Part One – Two Young People in the Summertime (2010)

The summer after Stephen and all his friends have finished school and they are deciding what comes next. Stephen and his long-known friend Del are both applying to study music. This summer they start to look at each in a different way, to feel something, they are light-footed, beach going, feeling like something good is coming.

When Stephen’s path changes course, he deals with isolation and separation, unable to even find solace in his instrument, the trumpet, or music. His emotions run deep and he withdraws from them.

Part Two – A Brief Intimacy (2011)

Stephen is working with his friend Nam, training to become a chef. The owner Femi has split allegiances, a Ghanaian mother and Nigerian father mean they serve Ghanaian food and play Nigerian music, and they all know about the 1983 Nigerian Presidential executive order, the mandate of Ghana Must Go that affected an estimated 2 million people living in the country.

Rhythm returns to his life and he feels it everywhere. The observations of bits of daily life, poetic, vibrant, rhythmic and upbeat.

Back in Peckham, it’s here too, this rhythm happening everywhere, as I take my time to wander home: in the dash of four boys dressed in black, trying to beat the bus round the curve, soft socks in sliders slapping the ground. The song of a passing car, distant bass finding a home in my ears, the low, slow rumble calling attention the way thunder might ask you to check the sky for rain. The haggling taking place at the butcher’s and the grocer’s, the disbelief that it’s now three plantain for a pound, not four. In the sadness as I pass the spot where Auntie Yaa’s shop used to be, where she would make sure everyone was looked after. In the joyful surprise when I run into Uncle T, his mouth full of gold like its own sunshine. The couple I pass in the park, holding each other close, her head turned away from his, a smile on his face even as he pleads with her, babe, I didn’t mean it. In the distance she holds him, to see if he’ll come closer, because sometimes it’s not enough to say it, you have to show it too. In the conviction I share with many that this stretch, from Rye Lane to Commercial Way, is where our small world begins and ends. There’s rhythm happening, everywhere; all of us like instruments, making our own music.

But expectations, old trauma and shame linger and until they can be addressed, they undermine relationships, cause rupture, rigidity and regret. So much still to recognise, dismantle, overcome and heal. And Stephen explores it all.

I’m slowly taking myself apart, so I might build myself up once more. And as part of this undoing, I want to ask him, why?And then there are those aspects of the outside world, not so far away, that seethe with unresolved anger and hatred, that threaten to close in on them. A raising of public consciousness and a shift in perception.

Part Three – Free (2012)

Stephen takes time off after the turn of events and pays a visit to Ghana. His trip heralds a reckoning.

Still, of late I’ve felt the urge for more. I’ve always had a decent grasp on who I am, or where I might find myself, but I’ve never really known where I’ve come from. This trip has started a shift. There are gaps which my father might fill, with his own story. I want him to tell me who he is, or who he was. I want to know who he was when he was twenty. I want to know what he dreams of, where he finds freedom.

Melody, discord, harmony and triumph – a story through music

As we read, there are songs Stephen chooses to accompany him. Often as I read, I stop to listen and look up the artist, reminding me of the enjoyment I had reading Bernice McFadden’s The Book of Harlan (reviewed here). It can add so much more to the experience, when music with a cultural influence is present, calibrating the reader’s imagination with the mood of the story.

The way the story comes full circle, when by the end, Stephen’s father accepts his son’s invitation to come with him, to share a meal, to listen to ‘Abrentsie’ by Gyedu-Blay Ambrolley, the book morphed into scenes of a wonderful film that I was simultaneously watching and reading. I wished I weren’t on the last pages, because it felt so good to witness the transmutation of emotion into a new way forward, that was something like the old, but different; accepted, something they will be able to nourish and grow from.

Highly Recommended.

I’m happy knowing I have still to read his debut, Open Water now being made into a BBC 8 part series.

Further Reading

Interview Guardian – Novelist Caleb Azumah Nelson: ‘there is a wholeness in living life not always afforded to black people’ – Apr 2023

Afreada – Caleb Azumah Nelson In Conversation – Interviewed by Nancy Adimora and Amanda Kingsley

Author Interview – 21 Questions with Caleb

Caleb Azumah Nelson, Author

Caleb Azumah Nelson is a British-Ghanaian writer and photographer living in south-east London.

His first novel, Open Water, won the Costa First Novel Award, Debut of the Year at the British Book Awards, and was a number-one Times bestseller. It was shortlisted for the Dylan Thomas Prize, the Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year Award, Waterstones Book of the Year, and longlisted for the Gordon Burn Prize and Desmond Elliott Prize. He was selected as a National Book Foundation ‘5 under 35’ honoree by Brit Bennett.

Small Worlds, his second novel won the Dylan Thomas Prize (2024) (a prize that celebrates exceptional literary talent aged 39 or under), cementing the 30-year-old British-Ghanaian author as a rising star in literary fiction. The judges had this to say:

“Amid a hugely impressive shortlist that showcased a breadth of genres and exciting new voices, we were unanimous in our praise for this viscerally moving, heartfelt novel. There is a musicality to Caleb Azumah Nelson’s writing, in a book equally designed to be read quietly and listened aloud. Images and ideas recur to beautiful effect, lending the symphonic nature of Small Worlds an anthemic quality, where the reader feels swept away by deeply realised characters as they traverse between Ghana and South London, trying to find some semblance of a home. Emotionally challenging yet exceptionally healing, Small Worlds feels like a balm: honest as it is about the riches and the immense difficulties of living away from your culture.”