I have had Annie Ernaux’s English translation of The Years on my bookshelf for some time now, since it was shortlisted for the International Booker Prize in 2019. It was originally published in French in 2008 (Les Années) and is considered to be her chef-d’œuvre. It is a non-fiction work that spans the years 1941 to 2006 in France.

Neither memoir or autobiography, it is a unique compilation of memory, experiences, judgments, of political, cultural, personal and collective statements and images that represent a woman living through those years.

It is bookended by descriptions of things seen that are likely never to be seen again.

All the images will disappear:

the woman who squatted to urinate in broad daylight, behind the shack that served coffee at the edge of the ruins in Yvetot, after the war, who stood, skirts lifted, to pull up her underwear and then returned to the café

the tearful face of Alida Valli as she danced with Georges Wilson in the film The Long Absence

There is no call for literary devices or beautification of language or hiding the crude, raw human elements that some may grimace at.

When Ernaux won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2022, she gave a speech entitled I Will Write to Avenge My People in which she described deciding on and finding her writing voice, that it would not be like that used by the esteemed writers she taught her students.

What came to me spontaneously was the clamour of a language which conveyed anger and derision, even crudeness; a language of excess, insurgent, often used by the humiliated and offended as their only response to the memory of others’ contempt, of shame and shame at feeling shame.

Raised by shopkeepers/cafe owners, she considered herself a class-defector through her education alongside the sons and daughters of bourgeoise families. She would find a way through the language she used to address that betrayal, to elude the gaze of the culturally privileged reader.

I adopted a neutral, objective kind of writing, ‘flat’ in the sense that it contained neither metaphors nor signs of emotion. The violence was no longer displayed; it came from the facts themselves and not the writing. Finding the words that contain both reality and the sensation provided by reality would become, and remain to this day, my ongoing concern in writing, no matter what the subject.

For Ernaux, class mobility is a violent, brutal process and she sees it as her duty to at least attempt, via her authorship, to make amends to those she remembers, has left behind and to not hide from her own perspective, actions, behaviours.

Knowing that The Years was considered her masterpiece, I decided to read some of her earlier short works, to engage with her style and thus appreciate this work all the more and that has certainly been the case. I began with the book she wrote of her father La Place (A Man’s Place), then of childhood Shame, and an affair Simple Passion. I do think it is a good idea to read some of these shorter works before taking on The Years.

In effect The Years is an attempt to collate and offer a faithful account of an entire generation, as it was viewed by one woman and the collective that she was part of. The narrative therefore is written from the perspective of ‘she‘ and ‘we‘, there is no ‘I‘. It is an observation of the times passing and the inclinations of people, for better or worse.

She would like to assemble these multiple images of herself, separate and discordant, thread them together with the story of her existence, starting with her birth during World War II up until the present day. Therefore, an existence that is singular but also merged with the movements of a generation.

We read and witness the impact of school, religion, the media, politics on a generation, alongside the cultural influences, the strikes, the films, the advertising, the village gossip and children’s cruelty.

Public or private, school was a place where immutable knowledge was imparted in silence and order, with respect for hierarchy and absolute submission, that is, to wear a smock, line up at the sound of the bell, stand when the headmistress or Mother Superior (but not a teaching assistant) entered the room, to equip oneself with regulation notebooks, pens and pencils, refrain from talking back when observations were made and from wearing trousers in the winter without a skirt over the top. Only teachers were allowed to ask questions. If we did not understand a word or explanation, the fault was ours. We were proud, as of a privilege, to be bound by strict rules and confinement. The uniform required of private institutions was visible proof of their perfection.

While some aspects will be universal, it is by its nature a collective and singular memory of a life in France. That will interest some and not others, but as someone who lives in France today, it is interesting to read of the familiar and also the references to the particular, the cultural, the influences.

Between what happens in the world and what happens to her, there is no point of convergence. They are two parallel series: one abstract, all information no sooner received than forgotten, the other all static shots.

Because it is clearly written over the many, many years, it comes across as being always in the now, as if she is time travelling into the various versions of the self over the years, looking and noting down the visual memories, remembering and accessing the perspective of the time they were in.

So her book’s form can only emerge from her complete immersion in the images from her memory in order to identify, with relative certainty, the specific signs of the times, the years to which the images belong, gradually linking them to others; to try to hear the words people spoke, what they said about events and things, skim it off the mass of floating speech, that hub bub that tirelessly ferries the wordings and rewordings of what we are and what we must be, think, believe, fear, and hope. All that the world had pressed upon her and her contemporaries she will reuse to reconstitute a common time, the one that made its way through the years of the distant past and glided all the way to the present. By retrieving the memory of collective memory in an individual memory, she will capture the lived dimension of History.

I found it an absolutely compelling read, filling in a lot of gaps and knowledge regarding French history that I happily encounter in this kind of format.

Highly recommended if you are interested in French cultural and personal history from a unique literary perspective.

Have you read any works by Annie Ernaux?

I have a few more shown here that I intend to read in the original French version.

Further Reading

The Guardian, Interview: ‘If it’s not a risk… it’s nothing’: Nobel laureate Annie Ernaux on her unapologetic career by Alice Blackhurst

The Guardian: Annie Ernaux: the 2022 Nobel literature laureate’s greatest works

Author, Annie Ernaux

Annie Ernaux was born in Seine-Maritime, France, in September 1940 and currently lives in Paris, France. In October 2022 she was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature.

Annie Ernaux grew up in Normandy and studied at Rouen University, before becoming a secondary school teacher. From 1977 to 2000, she was a professor at the Centre National d’Enseignement par Correspondance. Her books, in particular A Man’s Place and A Woman’s Story, have become contemporary classics in France. The Years, shortlisted for the International Booker Prize in 2019, won the Prix Renaudot in France in 2008 and the Premio Strega in Italy in 2016. In 2017 she was awarded the Marguerite Yourcenar Prize for her life’s work.

My friend then mentioned Viktor Frankl and interestingly, I learned he held a similar premise, but in the opposite direction. In terms of looking forward in life, we are likely to be more at peace and less prone to suffering if we have a ‘why’ in terms of our life’s meaning. So having our own ‘why’ is what we can focus on, looking forward, not back, at ourselves and not ‘the other’.

My friend then mentioned Viktor Frankl and interestingly, I learned he held a similar premise, but in the opposite direction. In terms of looking forward in life, we are likely to be more at peace and less prone to suffering if we have a ‘why’ in terms of our life’s meaning. So having our own ‘why’ is what we can focus on, looking forward, not back, at ourselves and not ‘the other’.

Viktor Emil Frankl, psychiatrist, was born March 26, 1905 and died September 2, 1997, in Vienna, Austria. He was influenced during his early life by Sigmund Freud and Alfred Adler, and earned a medical degree from the University of Vienna Medical School in 1930.

Viktor Emil Frankl, psychiatrist, was born March 26, 1905 and died September 2, 1997, in Vienna, Austria. He was influenced during his early life by Sigmund Freud and Alfred Adler, and earned a medical degree from the University of Vienna Medical School in 1930.

1.

1.  2.

2.  3.

3.  4.

4.  5. Braiding Sweetgrass by Robin Wall Kimmerer (2013) (Creative Non Fiction) (US) – In this remarkable collection of 32 essays, organised into 5 sections that follow the life cycle of sweetgrass, we learn about the philosophy of nature from the perspective of Native American Indigenous Wisdom, shared by a woman of native origin who is a scientist, botanist, teacher, mother.

5. Braiding Sweetgrass by Robin Wall Kimmerer (2013) (Creative Non Fiction) (US) – In this remarkable collection of 32 essays, organised into 5 sections that follow the life cycle of sweetgrass, we learn about the philosophy of nature from the perspective of Native American Indigenous Wisdom, shared by a woman of native origin who is a scientist, botanist, teacher, mother. 6.

6.  7.

7.  8.

8.  9.

9.  10.

10.  This year I found inspiration from two of my favourites in this field, and two new authors, all of them coming from renowned publisher

This year I found inspiration from two of my favourites in this field, and two new authors, all of them coming from renowned publisher

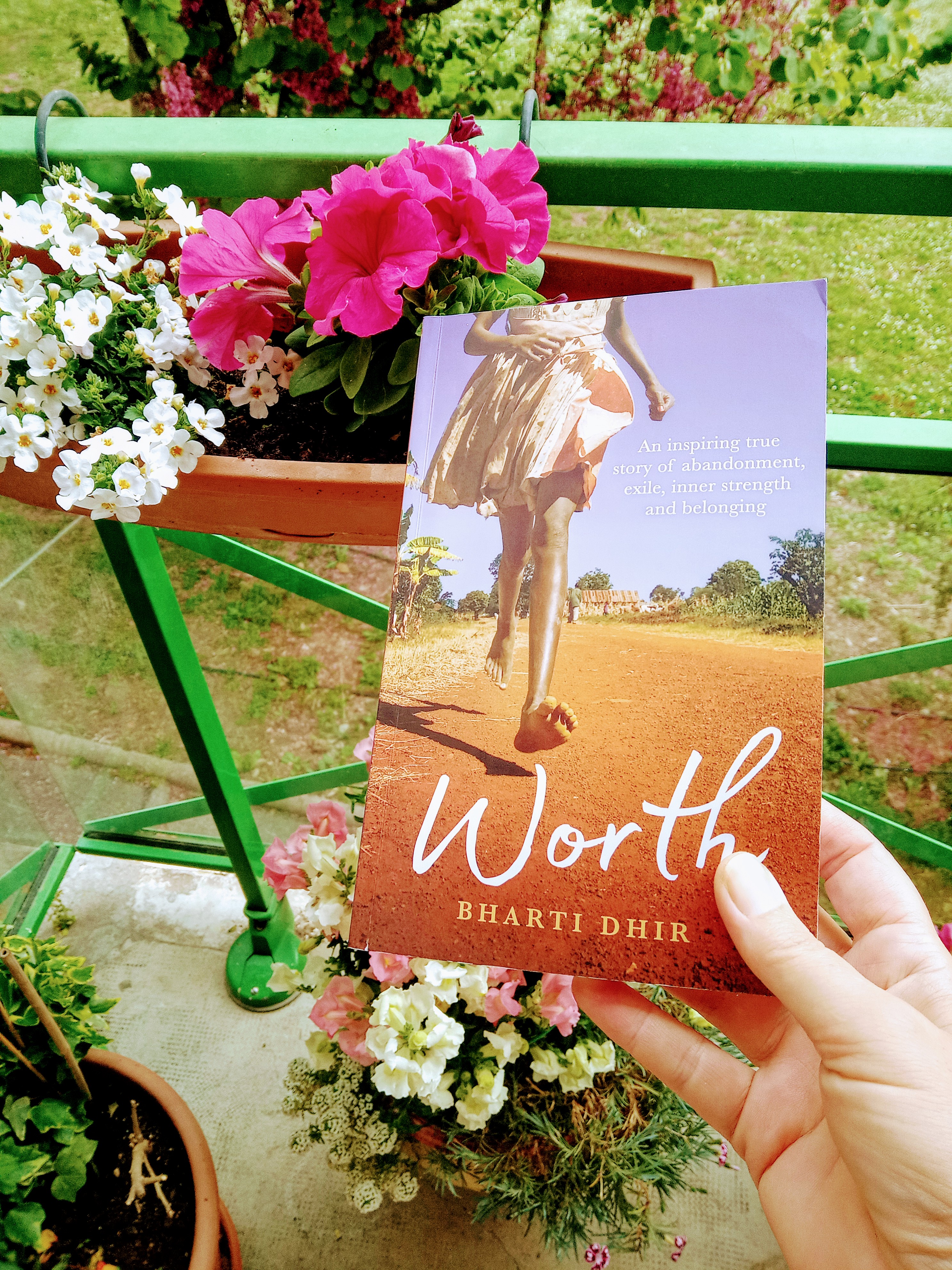

Another new author I picked up this year was Claire Stone and her book

Another new author I picked up this year was Claire Stone and her book  Finally,

Finally,  And now the final volume, Real Estate, which might as easily have been called UnReal Estate, in tumeric coloured silk, Levy has shed the cocoon, ready to embrace a new decade, the nest empty.

And now the final volume, Real Estate, which might as easily have been called UnReal Estate, in tumeric coloured silk, Levy has shed the cocoon, ready to embrace a new decade, the nest empty.

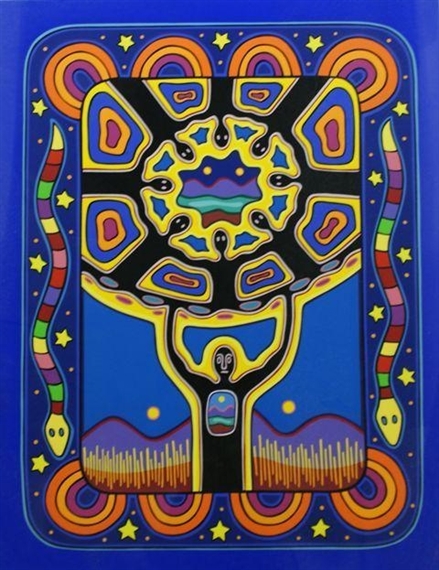

Sally Morgan is one of Australia’s best-known Aboriginal artists and writers.

Sally Morgan is one of Australia’s best-known Aboriginal artists and writers.

A voice repeated in my mind, ‘the master’s tools, the master’s house’ – you know when you recall a fragment of a quote but can’t quite remember it. It was the passionate sage wisdom of Audre Lorde reminding me of her essay, The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House in

A voice repeated in my mind, ‘the master’s tools, the master’s house’ – you know when you recall a fragment of a quote but can’t quite remember it. It was the passionate sage wisdom of Audre Lorde reminding me of her essay, The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House in

1. just open it and start reading taking in what is actually shared at face value, a woman on the cusp of a life change, whose suppressed emotions will no longer stay down, who leaves town to try and figure them out, looks back at her childhood and adolescence for inspiration, then decides to look forward instead and begins to write (on the last page);

1. just open it and start reading taking in what is actually shared at face value, a woman on the cusp of a life change, whose suppressed emotions will no longer stay down, who leaves town to try and figure them out, looks back at her childhood and adolescence for inspiration, then decides to look forward instead and begins to write (on the last page);

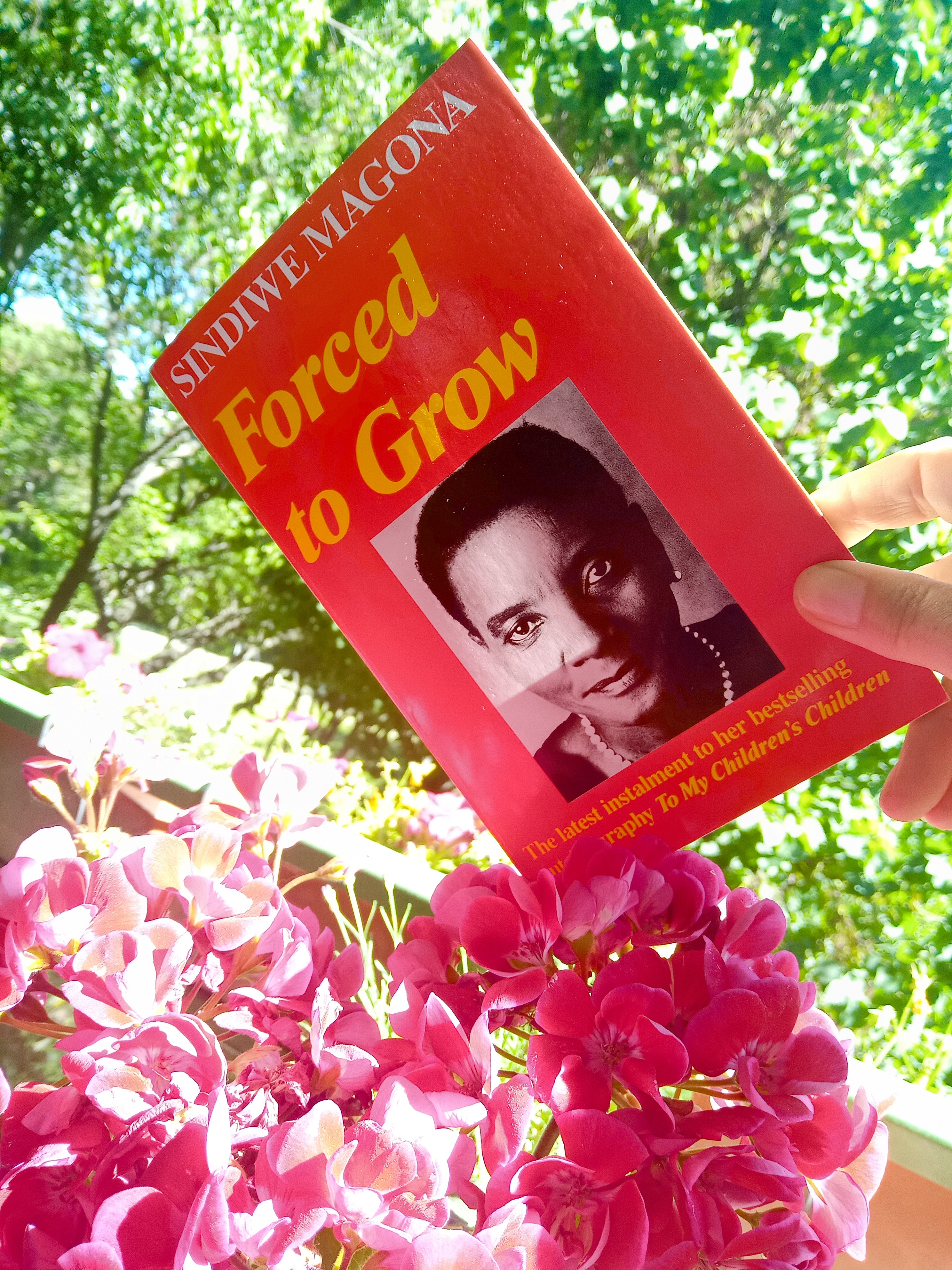

Finding herself unemployed and pregnant with her third child after being pushed out of a teaching job – her husband’s parting shot as he abandons his young family, to inform her employer of his disapproval (a husband’s approval was required for a married (black) woman to be eligible to work) – she reinvents herself, creating her own work (selling sheep heads (cooked) she’d bought on credit) initially to survive, determined to reinstate herself back into the teaching profession, to extend and elevate her education and move beyond surviving to thriving.

Finding herself unemployed and pregnant with her third child after being pushed out of a teaching job – her husband’s parting shot as he abandons his young family, to inform her employer of his disapproval (a husband’s approval was required for a married (black) woman to be eligible to work) – she reinvents herself, creating her own work (selling sheep heads (cooked) she’d bought on credit) initially to survive, determined to reinstate herself back into the teaching profession, to extend and elevate her education and move beyond surviving to thriving. Pursuing a higher level of education to offset so much else that set her back, fed into Magona’s ambition; as she achieved, her self belief grew and she pushed herself further, while assuming the role of both parents.

Pursuing a higher level of education to offset so much else that set her back, fed into Magona’s ambition; as she achieved, her self belief grew and she pushed herself further, while assuming the role of both parents. I was reminded of my recent read of Riane Eisler and Douglas Fry’s

I was reminded of my recent read of Riane Eisler and Douglas Fry’s