Stolen women. It sounds like an oxymoron, as if those two words cancel each other out, they should not go together, it should not exist.

Stolen women. It sounds like an oxymoron, as if those two words cancel each other out, they should not go together, it should not exist.

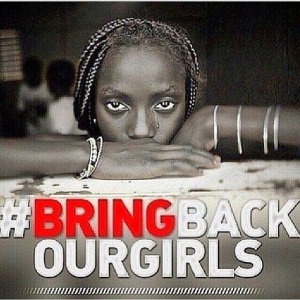

In the last month the #BringBackOurGirls campaign has raised awareness of the plight of stolen girls and women, the kidnapping of 200 high school girls from a boarding school in Nigeria bringing our attention to the proliferation of crimes that exist concerning the stealing or kidnapping of women. Modern day slavery. That it took so long for the story to come to the attention of the media and politicians disgusted many, making women feel like many third world countries feel – unimportant, insignificant, forgotten.

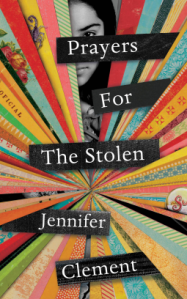

Prayers for the Stolen is the story of a girl named Ladydi, born in the mountain village of Guerrero in Mexico, what was once a real community, until it was ruined by the toxic effect of drug traffickers and immigration to the United States.

Prayers for the Stolen is the story of a girl named Ladydi, born in the mountain village of Guerrero in Mexico, what was once a real community, until it was ruined by the toxic effect of drug traffickers and immigration to the United States.

“Our angry piece of land was a broken constellation and each little home was ash.”

In this community families pray to give birth to sons, for daughters are cursed with everything that will mark them with the potential to become stolen. From a young age they blacken their faces and teeth, cut their hair short and their mothers clothe them as and tell people they are boys. They dig holes in the ground outside where they live and tell the girls to run and hide when they hear the big SUV’s with blackened windows approaching.

And when they hear the army helicopter, they run even faster, for it contains an even more deadly menace.

Ladydi lives alone with her mother, her father is working in the US. In the beginning he sent money but not now, some even say he has another family. Her mother plots her revenge against him daily, she has been doing so for a long time, before he even left she was consumed with vengeance, the naming of her daughter was one of her first acts of revenge.

Ladydi is friends with Maria, saved by a birth defect and Paula cursed by being born not just a girl, but a too beautiful one.

After eight years of waiting, doctors come to operate for free on children with deformities. Maria’s mother is reluctant to transform her daughter.

“Three army trucks were parked outside the clinic and twelve soldiers stood watch…

On one of the trucks someone had tacked a sign that said: Here doctors are operating on children.

These measures were taken so that the drug traffickers wouldn’t sweep down and kidnap the doctors and take them off.”

Maria’s brother Mike was the only boy on the mountain and as such indulged and spoiled, though now he is not often around, too busy, he turns up occasionally and his appearance changes noticeably over time. He has contacts and may be able to find Ladydi a job looking after the children of a well off family. Are her fortunes about to change?

I found this book a riveting read right from the first pages. It seems like an incredible story and yet it is clear that there are threads of truth running through the narrative, a terrible insight into the human trafficking trade. And despite the seriousness and tragic nature of the issues it deals with, it is not without humour and you can’t help but empathise with each of the female characters she so skilfully weaves together. We sense that their time together is limited but there are numerous memorable incidents that stay with the reader and endear us to this unique community of lost souls.

“A human being you can sell many, many times, whereas a bag of drugs you can sell once,” Clement, who has lived in Mexico since she was a year old, explains. “The trafficking of women is so horrific. You’d think that in this day and age there would be more equality and more fairness, and from what you see, it’s just not true.”

– Extract from interview by Stacey Bartlett

Jennifer Clement, in addition to writing four books of poetry, two novels and a work of non-fiction, was President of PEN Mexico for three years, where she investigated the killing of journalists (a crime no one has ever gone to prison for despite 75 being killed in the last decade). Her book is yet another way to raise awareness of the plight of women who are unable to speak out for themselves and she is a believer that literature can indeed change the world.

The book was inspired by the real village of Guerrero where poppy fields and heroin labs are hidden from view and Clement spent ten years researching the impact of drug and human trafficking on Mexican women. It is estimated that between 600,000 and 800,000 people are trafficked across international borders every year and that doesn’t include what goes on within national borders.

Prayers for the Stolen was a 5 star read for me, highly recommended.

Further Reading:

Interview – Stacey Bartlett’s excellent interview with Jennifer Clement

Review – New York Times book review by Gaby Wood

Note: This book was an Advance Reader Copy (ARC) kindly provided by the publisher via Netgalley.

Mexico to find work where they endure numerous perilous adventures including prison, first love, betrayal and death. Quite possibly the least bleak of McCarthy’s work, which may account in part for why I enjoyed it so much, but even his more downbeat work has much that I admire linguistically.

Mexico to find work where they endure numerous perilous adventures including prison, first love, betrayal and death. Quite possibly the least bleak of McCarthy’s work, which may account in part for why I enjoyed it so much, but even his more downbeat work has much that I admire linguistically. The first trip he attempts to return an injured, pregnant wolf he has trapped. Rather than kill her, he tries to return her to the mountains where she came from. The second journey with his brother Boyd is an attempt to retrieve stolen horses and the final crossing Billy makes alone

The first trip he attempts to return an injured, pregnant wolf he has trapped. Rather than kill her, he tries to return her to the mountains where she came from. The second journey with his brother Boyd is an attempt to retrieve stolen horses and the final crossing Billy makes alone  to find his missing brother and bring him home.

to find his missing brother and bring him home. within reach of his homestead and away from the troubles that lie in wait of the restless, idealistic man on a dubious if well-intended mission.

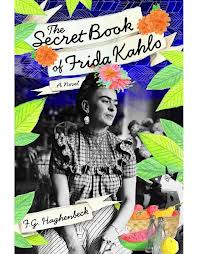

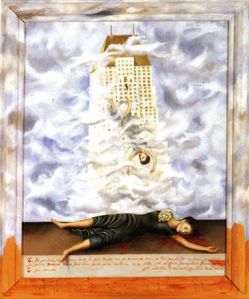

within reach of his homestead and away from the troubles that lie in wait of the restless, idealistic man on a dubious if well-intended mission. A ‘lucuna’ is a space or a void, a deep underwater cave, something hidden, unknown; already we see its metaphorical potential and Barbara Kingsolver puts it to good use in this excellent novel which intertwines the fictional story of 12 year old Shepherd, through historical events of Mexico and the US in the 1930’s and 40’s, including time spent in the household of Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo and their controversial houseguest Leon Trotsky.

A ‘lucuna’ is a space or a void, a deep underwater cave, something hidden, unknown; already we see its metaphorical potential and Barbara Kingsolver puts it to good use in this excellent novel which intertwines the fictional story of 12 year old Shepherd, through historical events of Mexico and the US in the 1930’s and 40’s, including time spent in the household of Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo and their controversial houseguest Leon Trotsky.