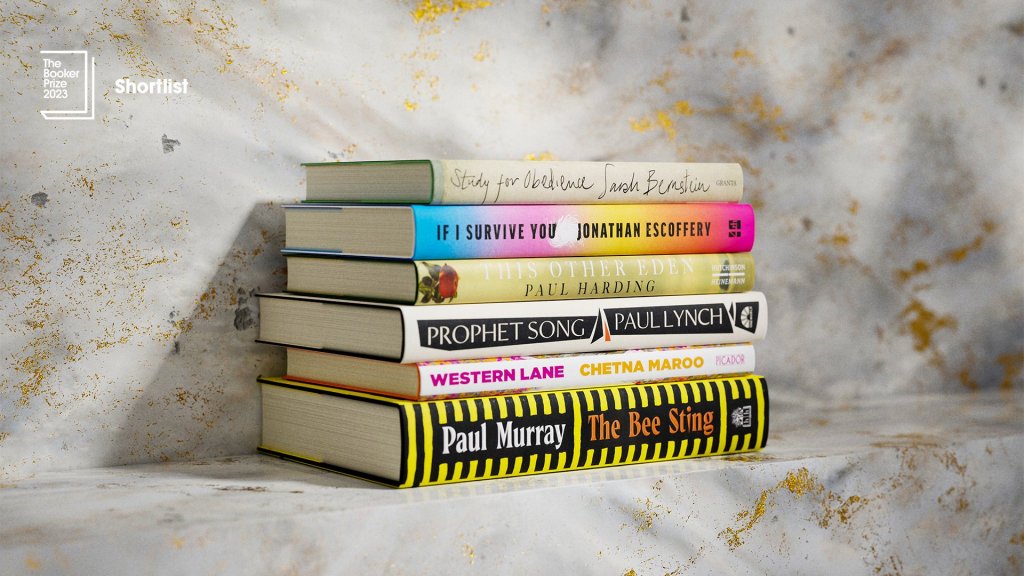

The shortlist for the International Booker Prize 2024 has been decided. It features novels from six countries, (Argentina, Brazil, Germany, Netherlands, South Korea and Sweden), translated from Dutch, German, Korean, Portuguese, Spanish and Swedish.

Chair of judges Eleanor Wachtel said:

‘Our shortlist, while implicitly optimistic, engages with current realities of racism and oppression, global violence and ecological disaster’

Prize Administrator Fiammetta Rocco added:

‘The books cast a forensic eye on divided families and divided societies, revisiting pasts both recent and distant to help make sense of the present’

Read Around the World, Other Perspectives

The International Booker Prize introduces readers to the best novels and short story collections from around the globe that have been translated into English and published in the UK and/or Ireland. Recognising the vital work of translators, the £50,000 prize money is divided equally: £25,000 for the author and £25,000 for the translator(s).

The shortlist was chosen from a longlist of 13 titles announced in March, which was selected from 149 books published in the UK and/or Ireland between May 1, 2023 and April 30, 2024, submitted to the prize by publishers.

I have read one from the shortlist and it was excellent; Selva Almada’s Not a River (link to my review), the second of her novella’s I have read. Not having read any others on this list, I can’t really comment, but I would love to know what you thought if you have read any of these, or intend to. Brief summaries below.

The Shortlist

Not a River by Selva Almada (Argentina) tr. by Annie McDermott

Selva Almada’s novel is the finest expression yet of her compelling style and singular vision of rural Argentina.

Three men go out fishing, returning to a favourite spot on the river despite their memories of a terrible accident there years earlier. As a long, sultry day passes, they drink and cook and talk and dance, and try to overcome the ghosts of their past. But they are outsiders, and this intimate, peculiar moment also puts them at odds with the inhabitants of this watery universe, both human and otherwise. The forest presses close, and violence seems inevitable, but can another tragedy be avoided?

Mater 2-10 by Hwang Sok-yong (Korea) tr. Sora Kim-Russell, Youngjae Josephine Bae

An epic, multi-generational tale that threads together a century of Korean history.

Centred on three generations of a family of rail workers and a laid-off factory worker staging a high-altitude sit-in, Mater 2-10 vividly depicts the lives of ordinary working Koreans, starting from the Japanese colonial era, continuing through Liberation, and right up to the twenty-first century.

What I’d Rather Not Think About by Jente Posthum (Netherlands) tr. Sarah Timmer Harvey

A deeply moving exploration of grief, told in brief, precise vignettes and full of gentle melancholy and surprising humour.

What if one half of a pair of twins no longer wants to live? What if the other can’t live without them? This question lies at the heart of Jente Posthuma’s deceptively simple What I’d Rather Not Think About. The narrator is a twin whose brother has recently taken his own life. She looks back on their childhood, and tells of their adult lives: how her brother tried to find happiness, but lost himself in various men and the Bhagwan movement, though never completely.

Crooked Plow by Itamar Vieira Junior (Brazil) tr. Johnny Lorenz

A fascinating and gripping story about the lives of subsistence farmers in Brazil’s poorest region.

Deep in Brazil’s neglected Bahia hinterland, two sisters find an ancient knife beneath their grandmother’s bed and, momentarily mystified by its power, decide to taste its metal. The shuddering violence that follows marks their lives and binds them together forever.

Kairos by Jenny Erpenbeck (Germany) tr. Michael Hofmann

An intimate and devastating story of the path of two lovers through the ruins of a relationship, set against the backdrop of a seismic period in European history.

Berlin. 11 July 1986. They meet by chance on a bus. She is a young student, he is older and married. Theirs is an intense and sudden attraction, fuelled by a shared passion for music and art, and heightened by the secrecy they must maintain. But when she strays for a single night he cannot forgive her and a dangerous crack forms between them, opening up a space for cruelty, punishment and the exertion of power. And the world around them is changing too: as the GDR begins to crumble, so too do all the old certainties and the old loyalties, ushering in a new era whose great gains also involve profound loss.

The Details by Ia Genberg (Sweden) tr. Kira Josefsson

In exhilarating, provocative prose, Ia Genberg reveals an intimate and powerful celebration of what it means to be human.

A famous broadcaster writes a forgotten love letter; a friend abruptly disappears; a lover leaves something unexpected behind; a traumatised woman is consumed by her own anxiety. In the throes of a high fever, a woman lies bedridden. Suddenly, she is struck with an urge to revisit a particular novel from her past. Inside the book is an inscription: a message from an ex-girlfriend. Pages from her past begin to flip, full of things she cannot forget and people who cannot be forgotten. Johanna, that same ex-girlfriend, now a famous TV host. Niki, the friend who disappeared all those years ago. Alejandro, who appears like a storm in precisely the right moment. And Birgitte, whose elusive qualities shield a painful secret. Who is the real subject of a portrait, the person being painted or the one holding the brush?

The Winner

The International Booker Prize 2024 ceremony will take place from 7pm BST on Tuesday, 21 May. It is being held for the first time in the Turbine Hall at London’s Tate Modern.

Highlights from the event, including the announcement of the winning book for 2024, will be livestreamed on the Booker Prizes’ channels, presented by Jack Edwards.