I’ve loved Georgia O’Keeffe’s paintings since I stumbled across them one weekend in an art gallery in Chicago and felt the effect of them, rather than saw them as such, for they are indeed imbued with feeling and when you see one of her large canvases with its bold visual statement, well for me anyway, you can’t help but be moved by it, struck dumb by it, to stop and appreciate how this artist communicated something deep within you, without words or reality. I felt it almost like a punch, I didn’t quite understand what it was, but I wanted to know who is was that had created that effect on me.

Although I bought a beautiful book about her paintings, it was something less intellectual and more personal I was after. I found a very old, yellowed copy of Laurie Lisle’s Portrait of an Artist: A Biography of Georgia O’Keeffe.

It provided an excellent framework of her life, her childhood and introduction to art, her various shows, her marriage and need for solitude and her eventual move to that part of the world that most resonated with her, New Mexico.

However, O’Keeffe comes off as a rather distant, aloof character, seen from the outside, rather brusque, detached. The biography filled in her life, but left me still wanting to know who she was, sure there was much more to her that we would benefit from knowing.

One of the things that makes Georgia O’Keeffe such an interesting character is not just her work, but her essence, her self-knowledge and ability to act upon it, to ensure that she lived in a way that allowed her art to express itself in an authentic way. When she wasn’t able to do this, her mental health declined, however she knew how to resolve it and in acting accordingly, lived to the age of 98.

She married the well-known gallery owner and photographer, Alfred Stieglitz, something of a scandal as she was 25 years his junior and he left an unhappy marriage for her, but she never collapses into the relationship, they find a way of supporting each other, that also allows them be individuals and to pursue (most of) their own ambitions wholeheartedly.

Inevitably there would always be compromise, Stieglitz accepted that O’Keeffe needed to spend a portion of the year in New Mexico without him and O’Keeffe had to accept that Stieglitz did not want to become a father again.

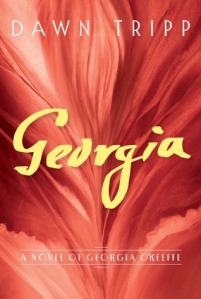

Which all leads me on to say it was with quiet anticipation to learn that Dawn Tripp had the courage, respect and admiration for O’Keeffe to decide to venture into creating a work of fiction, that attempts to channel the voice of Georgia O’Keeffe. What might she have really been thinking if it was her voice relating the story of this life and not someone from the outside.

Which all leads me on to say it was with quiet anticipation to learn that Dawn Tripp had the courage, respect and admiration for O’Keeffe to decide to venture into creating a work of fiction, that attempts to channel the voice of Georgia O’Keeffe. What might she have really been thinking if it was her voice relating the story of this life and not someone from the outside.

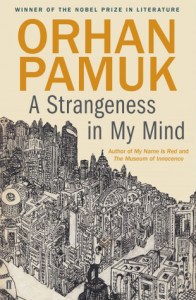

Georgia: A Novel of Georgia O’Keeffe does exactly that.

Dawn Tripp similarly came across her story through her art, after seeing an exhibition of her abstractions at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 2009. She had been aware of her work, but experienced something different that day.

As early as the fall of 1915, at twenty-nine-years old, she was creating radical abstract forms when only a handful of artists were bold enough to explore this new language of modern art. Her abstractions of that time – and those she continued to create throughout her life – were ambitious, gorgeous shapes of colour and form designed to express and evoke emotion, and they were stunningly original.

It provokes in the author, a desire to want to know this woman, the artist, the creator of these stunning works and why she was not recognised for the visionary power of these abstractions during her lifetime. There were excerpts from letters as part of the show:

The language of those letters was sharply intimate, vulnerable, complex. O’Keeffe’s letters revealed a woman of exceptional passion, a rigorous intelligence, and a strong creative drive. Her letters had a raw heat that felt deeply aligned with the abstract pictures I was seeing on the walls, but at odds with the image of O’Keeffe I’d grown up with: the aged doyenne of the Southwest, poised and cool, holding the world at arm’s length.

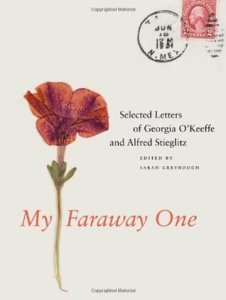

When the novel was almost complete, the correspondence of O’Keeffe and Stieglitz was published, having been sealed for twenty-five years after her death.

When the novel was almost complete, the correspondence of O’Keeffe and Stieglitz was published, having been sealed for twenty-five years after her death.

It was a pleasure to read this novel that attempts to get inside that mind and share something that feels more genuine in terms of what her work intended, than the easy reference that so many of the male critics of the time jumped to, insinuating the sexual by responding to the visual elements of Stieglitz’s nude photos of her and the soft interior of her giant flowers, rather than the essence of life itself pushing forth.

This is the Georgia O’Keeffe I’ve wanted to know, and suspected existed, from someone who has tried to absorb her childhood, upbringing and place in the world, attempting to understand what she was trying to express and how it was both uplifted and repressed by the decisions she made.

To explore those initial choices, few of which were her own, the effect of Steiglitz managing and directing her career, their relationship, her need for a child, their life between New York and Lake George until the moment when she allows herself to visit New Mexico with her friend Beck and begins an annual pilgrimage to a place that will eventually consume her entirely and become her home, both physically and spiritually.

We see O’Keeffe as a young independent woman, learn about her family background, their vulnerability to TB, the shock of meeting Stieglitz’s wife and family, the abundance of material wealth and food, she so close to nature – and yet so attracted to him, his mind and his person.

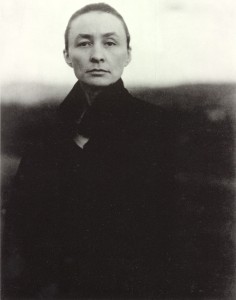

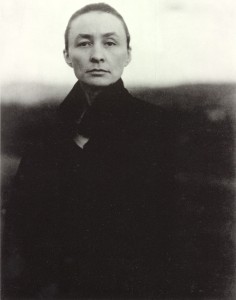

Georgia O’Keeffe, 1920

She resents her art being seen through his lens of her, by the critics, that association with gender, the feminine. The thing that builds her up, blinds them to the work as she sees it. She seeks solitude. She resists being photographed, unable to convince through other means. By the time Stieglitz divorces, Georgia is lacklustre on marriage.

Her mental decline from accepting it all, the inevitable, necessary turning point, turning away from her husband, though forever connected to him.

Dawn Tripp has us completely immersed in a perception of the life of Georgia O’Keeffe that feels as real as if it were the artist herself speaking, though we all know how private she was, and through this novel we understand that need even more so.

People can be sceptical of the fictional biography, but when it is well researched, and the author has found the appropriate voice, and treats the subject with respect and understanding, it brings history alive and makes it accessible to a much wider audience than the more traditional, detached form of narrative.

I highlighted so many paragraphs and sections in the book, it would make the review too long to show them. All the better to discover the words for yourself.

Absolutely brilliant, loved it.

Notes on the Paintings Depicted

“Pink Tulip”, 1926, Georgia O’Keeffe, oil on canvas, 36” x 30”

“Pink Tulip”, 1926, Georgia O’Keeffe, oil on canvas, 36” x 30”

The Baltimore Museum of Art, Bequest of Mabel Garrison Siemonn, in memory of her husband George Siemonn.

©Georgia O’Keeffe Museum

Georgia O’Keeffe, Untitled (City Night) (Untitled – Night city), Seventies © 2009 Georgia O’Keeffe Museum / © Georgia O

Georgia O’Keeffe White Iris, No. 7 (White Iris # 7), 1957 © 2009 by Georgia O’Keeffe Museum / © Georgia O

Georgia O’Keeffe, “Ram’s Head White Hollyhock and Little Hills,” 1935, Oil on canvas, 30 x 36 in. Brooklyn Museum, New York.

Click on the link to buy this book.

Note: The book was an ARC (Advance Reader Copy) kindly provided by the publisher via Netgalley.

The other literary event that has been progressing while I was offline is the Baileys Women’s Prize for Fiction.

The other literary event that has been progressing while I was offline is the Baileys Women’s Prize for Fiction.

While adrift from the internet and with little time to read and review, I missed this literary event, which I’ll still mention as it’s one of the literary highlights of the year for readers of world and translated fiction like me.

While adrift from the internet and with little time to read and review, I missed this literary event, which I’ll still mention as it’s one of the literary highlights of the year for readers of world and translated fiction like me. The most popular literature languages translated into English in 2015 were French, Italian, Japanese, Swedish and German while the top-selling author was Elena Ferrante, with her all-consuming, Neapolitan series of four books:

The most popular literature languages translated into English in 2015 were French, Italian, Japanese, Swedish and German while the top-selling author was Elena Ferrante, with her all-consuming, Neapolitan series of four books:

The book I reviewed was Lloyd Jones Paint Your Wife.

The book I reviewed was Lloyd Jones Paint Your Wife.

Buddha in the Attic is a unique novella told in the first person plural “we”, narrating the story of a group of young women brought from Japan to San Francisco as “picture brides” nearly a century ago.

Buddha in the Attic is a unique novella told in the first person plural “we”, narrating the story of a group of young women brought from Japan to San Francisco as “picture brides” nearly a century ago. And as if it couldn’t get any worse, war happens, and they discover they are the enemy, they are regarded suspiciously and in time sent away.

And as if it couldn’t get any worse, war happens, and they discover they are the enemy, they are regarded suspiciously and in time sent away. It reminded me, not in style, but in subject of Jamie Ford’s

It reminded me, not in style, but in subject of Jamie Ford’s  Today is International Women’s Day, this year the theme is #PledgeForParity and the Baileys Women’s Prize certainly does a lot to advance that challenge, with their ambition to bring the best women’s writing and female storytellers to ever-wider audiences.

Today is International Women’s Day, this year the theme is #PledgeForParity and the Baileys Women’s Prize certainly does a lot to advance that challenge, with their ambition to bring the best women’s writing and female storytellers to ever-wider audiences.

Which all leads me on to say it was with quiet anticipation to learn that Dawn Tripp had the courage, respect and admiration for O’Keeffe to decide to venture into creating a work of fiction, that attempts to channel the voice of Georgia O’Keeffe. What might she have really been thinking if it was her voice relating the story of this life and not someone from the outside.

Which all leads me on to say it was with quiet anticipation to learn that Dawn Tripp had the courage, respect and admiration for O’Keeffe to decide to venture into creating a work of fiction, that attempts to channel the voice of Georgia O’Keeffe. What might she have really been thinking if it was her voice relating the story of this life and not someone from the outside. When the novel was almost complete, the correspondence of O’Keeffe and Stieglitz was published, having been sealed for twenty-five years after her death.

When the novel was almost complete, the correspondence of O’Keeffe and Stieglitz was published, having been sealed for twenty-five years after her death.

“Pink Tulip”, 1926, Georgia O’Keeffe, oil on canvas, 36” x 30”

“Pink Tulip”, 1926, Georgia O’Keeffe, oil on canvas, 36” x 30”

Jane Bowles (born in New York City, Feb 1917) wrote one novel, a play and six short stories. The novel Two Serious Ladies, though panned at the time, (critic Edith Walton writing in the Times Book Review didn’t understand it, calling it ‘senseless and silly’), became regarded as a modernist, cult classic, helped when Tennessee Williams named it his favourite book.

Jane Bowles (born in New York City, Feb 1917) wrote one novel, a play and six short stories. The novel Two Serious Ladies, though panned at the time, (critic Edith Walton writing in the Times Book Review didn’t understand it, calling it ‘senseless and silly’), became regarded as a modernist, cult classic, helped when Tennessee Williams named it his favourite book.

The novel unfolds and weaves like threads in a tapestry, as characters share their understanding of Billy, their memories of his charm and inclinations and what they knew about the short-lived romance with the Irish girl Eva.

The novel unfolds and weaves like threads in a tapestry, as characters share their understanding of Billy, their memories of his charm and inclinations and what they knew about the short-lived romance with the Irish girl Eva.

From whispering muse to the gift of stones, this was the second book I read in 2016, one of Jim Crace’s earlier philosophical works, telling the tale of a village of stone workers, who live a simple life working stone into weapons, which are then traded with passers-by for food and other essentials, which they are not able to provide for themselves, in the arid landscape within which they reside. It is a livelihood they think little about, it is all they know.

From whispering muse to the gift of stones, this was the second book I read in 2016, one of Jim Crace’s earlier philosophical works, telling the tale of a village of stone workers, who live a simple life working stone into weapons, which are then traded with passers-by for food and other essentials, which they are not able to provide for themselves, in the arid landscape within which they reside. It is a livelihood they think little about, it is all they know.