Women of Courage, WWII

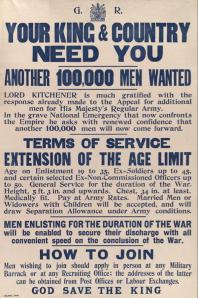

Juliet Greenwood writes immersive historical fiction, often set in Wales or Cornwall around World War II and always featuring women protagonists, who rise to the challenge in difficult times. Her books are a tribute to those women, often unseen, who keep the world turning, even in the most terrible of times.

I have been following Juliet’s progress and reading her books since she wrote Eden’s Garden and I have also read and reviewed We That are Left and The Ferryman’s Daughter.

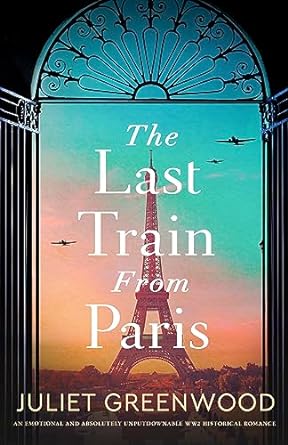

The Last Train from Paris is set in the period just before and during World War II, moving from Paris, to London to Cornwall and was inspired in part by stories that Juliet’s mother told her about this period.

It’s a story I’ve been longing to write, ever since I was a little girl and my Mum first told me about studying French near Paris on the day war broke out in 1939. I couldn’t imagine then what it must have been liketo have been a 17-year-old English girl, on her own, catching the train to Calais through a country preparing for war and, like Nora, finding herself on a ferry in the middle of the Channel, being stalked by a German submarine. It’s a story that’s haunted me, especially since we found the letters Mum exchanged with my Dad in London, and the scribbled note she sent him when she finally arrived in Dover.

Past Circumstances, Present Lives

1964: Iris is visiting her mother in St Mabon’s Cove, Cornwall, an escape from her life in London. She has been having nightmares of feeling trapped. Her mother has given her a box. She has also been looking at the objects in it that relate to her past. It is awakening something that has become more insistent. She knows she was adopted and that these items have something to do with her original family.

Over the course of the weekend, she will ask her mother questions and begin to learn about the past. And encounter a strange reporter is snooping around the village asking questions, a caller her mother wishes to ignore.

Studying in Paris, 1939

The historical narrative centres around two young women characters in 1939; Nora lives in London, where she has worked as a dish washer in a kitchen since she was sixteen. Sabine, a freelance journalist works in a boulangerie (bakery) in Paris, living with her husband Emil, also a journalist, who is focused on writing the novel that is going to change their lives.

The two women meet when Sabine gives a talk in London, after spending a month gaining work experience at the London Evening Standard newspaper. They maintain contact, writing each letters regularly.

Nora, frustrated with the lack of opportunity in her job, comes up with the idea of going to Paris to do a chef training course at Madame Godeaux’s Cuisine Française, seeing no chance of promotion in her current employment.

The Risk of Relying on the Family Business

Sabine and Emil’s lives are a little precarious due to their reliance on Emil’s brother Albert to subsidise their rent and pending war has contributed to the family boot business suffering. When bad news arrives, Emil, as the second son, is summoned to return to Colmar, to take over from his brother.

When Nora arrives in Paris, she is disappointed to learn that Sabine has already left for Colmar, but she settles into her course and meets other girls, amid a growing wariness of the safety of the city. When one of the girls Heidi tells her the real reason she is in Paris, Nora begins to understand the danger that is not far away.

The novel follows the twin time periods, the present day 1964 where Iris hearing from her mother stories of the past that will lead towards her understanding her identity and circumstances that lead to where she is now and the crossing of paths of two women in the past whose connection resulted in lives being forever changed.

As the story gathers pace, secrets are revealed, dangers confronted and choices made in desperation have long term effects.

There are so many twists and turns in the story, it’s one that you won’t want to put down once started, bt to share any more would be to spoil the joy of discovering and the detective work we begin to do as readers, trying to puzzle out the missing pieces of the jigsaw of these three women’s lives.

A riveting and immersive read, that reminds us just how precarious life is, how stability can be shattered from one day to the next, yet offers hope in its demonstration of the acts of kindness some will make to help others, to make each other safe.

N.B. Thanks you to the author Juliet Greenwood, for providing me a copy of the book to read and review.

The character of Ann we meet in 1898, on a bridge overlooking the Thames at a low point in her life, seeking refuge at a Charity Hospital.

The character of Ann we meet in 1898, on a bridge overlooking the Thames at a low point in her life, seeking refuge at a Charity Hospital.