Yesterday via a link on twitter, I read a provocative article in BBC News Magazine by Hugh Schofield entitled Why don’t French books sell abroad? It was an interesting, if superficial article, that made a few observations without going into any depth to understand the contemporary literary scene in France. It asked questions, reminded us of some old provocative stereotypes and did little to enlighten us on the subject of what excites French readers and why the English-speaking world aren’t more aware of their contemporary literary gems.

Kate from BooksKateRates, reads and blog about French literature and wrote an interesting blog post in response to the article and I have been scribbling notes since reading the original article. I plan to share them here, as it is a fascinating subject if one takes the time to research and understand it.

But firstly, I wanted to show you the library, as it offers a glimpse into how the French absorb literature and culture and it’s one our favourite local hangouts.

Situated in what was a 14,500 sqm match factory, the library, La Bibliothèque Mèjanes, is part of the Cité du livre, a centre for the arts and culture which includes an auditorium for lectures and readings, rooms for more formal lectures, a small cinema showing themed films for 3 week periods (currently Humphrey Bogart films), a music and film lending room, adult and children’s libraries, a press room, an exhibition space (currently celebrating the centenary of Albert Camus), a café and plenty of space for research and study.

As we walk in through the enormous sculptures of the covers of Camus’s L’etranger on one side and Saint-Exupéry’s Le Petit Prince and Molière on the other, we arrive in a long corridor and the reception area for borrowing and returning books.

Turn left and we head towards the reading library where outside the door is a display of books for adolescents. A quick glance at these books shows us that half of them are translated fiction, from South African, German and Hispanic authors.

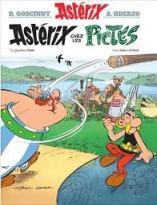

Inside, we walk past displays of translated literature originating from South Africa, a tribute to Nelson Mandela, then the stacks of Bande Dessinée, the very popular hardcover graphic novels, which even today remain at the top of the French bestsellers list, right now its Asterix chez les Pictes, visiting the people of ancient Scotland!

Inside, we walk past displays of translated literature originating from South Africa, a tribute to Nelson Mandela, then the stacks of Bande Dessinée, the very popular hardcover graphic novels, which even today remain at the top of the French bestsellers list, right now its Asterix chez les Pictes, visiting the people of ancient Scotland!

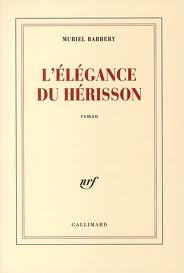

And here are the novels, in French called romans. Rows and rows of books and you might notice something they all have in common, well, in fact, something they all lack. Colour.

Compare it to the shelf opposite which contains the English language novels. It certainly removes that whole likelihood of an impulse buy based on an intriguing cover.

Most French literary novels are published without fancy colourful covers and while in the bookshop you might find first editions with promotional covers, there are many more with pale or cream covers without images and a black or red text title.

However, after looking around a little more, I discover that there is colour in some sections. Science Fiction and Fantasy are full of dark colours and the books covers in the section entitled Policiers (Crime) are mostly black. However, novels and poetry, even the section called American Literature pale into insignificance among a sea of white. It reminds me of one of the three principles of France l’égalitié and certainly here, all books have the same chance of being found, whether it’s from the library or in the bookshop, not just due to their bland covers, but also due to a government policy called le plan livre and the fixed price of books.

It costs €17.50 to join the library (adult) and its free for children, there is no cost for lending and no fees for late returns. 16 items (books and CD’s) and 3 DVD’s can be borrowed at any one time for a period of 3 weeks and the first renewal can be done online. The library is also full of computers providing free internet access to all members. My only complain is that its closed on Sunday and Monday. C’est la vie en France!

So what kind of books do French people read today? And is it true that nearly half of the fiction read is translated foreign fiction? And why don’t we see more books by French authors in English bookshops? These questions and more I will talk about in the next post Reading Contemporary French literature.

In the meantime, if you want to know what’s popular in France and available now to read in English, check out Gallic Books, who offer the best of what’s available in French translated in English with new titles coming out every month.

In the meantime, if you want to know what’s popular in France and available now to read in English, check out Gallic Books, who offer the best of what’s available in French translated in English with new titles coming out every month.

I’m looking forward to reading The People in the Photo by Hélène Gestern due out in English in February 2014. If you wish to read it in French, it’s already available with the title Eux sur la photo.