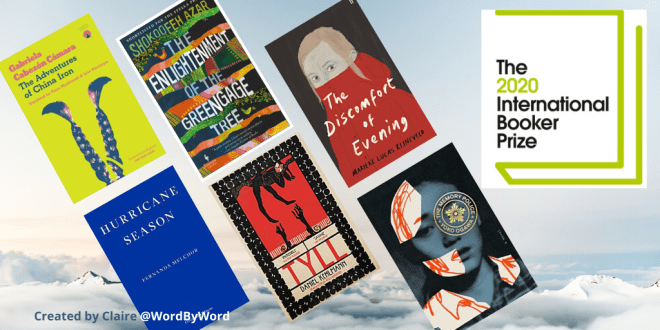

Since I’ve been in a bit of a reading slump I didn’t post about the International Booker longlist when it came out, and to be honest, nothing on it really jumped out at me, so I felt little motivation to share it.

However I do like to have a record of what was highlighted, so I’m sharing below the six books that have made the shortlist and below that the longlist. Clicking on any of the titles will take you a description of the book.

I don’t have any of these to read and I’m unlikely for the moment to add to my list of reading, since I’m looking for more of an uplifting read at the moment.

The 2021 International Booker Prize longlist

I Live in the Slums by Can Xue, translated from Chinese by Karen Gernant & Chen Zeping, Yale University Press

At Night All Blood is Black by David Diop, translated from French by Anna Mocschovakis, Pushkin Press

A novel that captures the tragedy of a young man’s mind hurtling towards madness and tells the little-heard story of the Senegalese who fought for France on the Western Front during WW1.

Alfa Ndiaye and Mademba Diop are two of the many Senegalese tirailleurs fighting in the Great War under the French flag. Whenever Captain Armand blows his whistle they climb out of their trenches to attack the blue-eyed enemy. One day Mademba is mortally wounded, and without his friend, his more-than-brother, Alfa is alone amidst the savagery of the trenches, far from all he knows and holds dear. He throws himself into combat with renewed vigour, but soon begins to scare even his own comrades in arms.

The Pear Field by Nana Ekvtimishvili, translated from Georgian by Elizabeth Heighway, Peirene Press

The Dangers of Smoking in Bed by Mariana Enríquez, translated from Spanish by Megan McDowell, Granta Books

Unruly teenagers, crooked witches, homeless ghosts, and hungry women, these stories walk the uneasy line between urban realism and horror, with a resounding tenderness toward those in pain, in fear and in limbo. As terrifying as they are socially conscious, the stories press into the unspoken – fetish, illness, the female body, the darkness of human history – with bracing urgency. A woman is sexually obsessed with the human heart; a lost, rotting baby crawls out of a backyard and into a bedroom; a pair of teenage girls can’t let go of their idol; an entire neighbourhood is cursed to death when it fails to respond correctly to a moral dilemma.

When We Cease to Understand the World by Benjamín Labatut, translated from Spanish by Adrian Nathan West, Pushkin Press

Albert Einstein opens a letter sent to him from the Eastern Front during the First World War. Inside, he finds the first exact solution to the equations of general relativity, unaware that it contains a monster that could destroy his life’s work. The great mathematician Alexander Grothendieck tunnels so deeply into abstraction that he tries to cut all ties with the world, terrified of the horror his discoveries might cause. Erwin Schrödinger and Werner Heisenberg battle over the soul of physics after creating two equivalent yet opposed versions of quantum mechanics. Their fight will tear the very fabric of reality, revealing a world stranger than they could have ever imagined.

The Perfect Nine: The Epic Gikuyu and Mumbi by Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, translated from Gikuyu by the author, VINTAGE, Harvill Secker

The Employees by Olga Ravn, translated from Danish by Martin Aitken, Lolli Editions

Structured as a series of witness statements compiled by a workplace commission, The Employees follows the crew of the Six-Thousand Ship which consists of those who were born, and those who were made, those who will die, and those who will not. When the ship takes on a number of strange objects from the planet New Discovery, the crew is perplexed to find itself becoming deeply attached to them, and human and humanoid employees alike start aching for the same things: warmth and intimacy, loved ones who have passed, shopping and child-rearing, our shared, far-away Earth, which now only persists in memory.

Gradually, the crew members come to see their work in a new light, and each employee is compelled to ask themselves whether they can carry on as before – and what it means to be truly living. Wracked by all kinds of longing, The Employees probes what it means to be human, emotionally and ontologically, while simultaneously delivering an overdue critique of a life governed by work and the logic of productivity.

Summer Brother by Jaap Robben, translated from Dutch by David Doherty, World Editions

An Inventory of Losses by Judith Schalansky, translated from German by Jackie Smith, Quercus, MacLehose Press

Minor Detail by Adania Shibli, translated from Arabic by Elisabeth Jaquette, Fitzcarraldo Editions

In Memory of Memory by Maria Stepanova, translated from Russian by Sasha Dugdale, Fitzcarraldo Editions

The story of how a seemingly ordinary Jewish family somehow managed to survive the myriad persecutions and repressions of the last century. Following the death of her aunt, Maria Stepanova builds the story out of faded photographs, old postcards, letters, diaries, and heaps of souvenirs left behind: a withered repository of a century of life in Russia.

In dialogue with writers like Roland Barthes, W. G. Sebald, Susan Sontag and Osip Mandelstam, In Memory of Memory is imbued with intellectual curiosity and a soft-spoken, poetic voice. Dipping into various forms – essay, fiction, memoir, travelogue and historical documents – Stepanova assembles a vast panorama of ideas and personalities and offers an entirely new and bold exploration of cultural and personal memory.

Wretchedness by Andrzej Tichý, translated from Swedish by Nichola Smalley, And Other Stories

The War of the Poor by Éric Vuillard, translated from French by Mark Polizzotti, Pan Macmillan, Picador

The Protestant Reformation of the 16th century takes on the powerful and the privileged. It quickly becomes more about the bourgeoisie. Peasants, the poor living in towns, who are still being promised that equality will be granted to them in heaven, begin to ask themselves: and why not equality now, here on earth? There follows a furious struggle. Out of this chaos steps Thomas Müntzer, a complex and controversial figure. Sifting through history, Éric Vuillard extracts the story of one man whose terrible and novelesque life casts light on the times in which he lived – a moment when Europe was in flux. Inspired by the recent gilets jaunes protests in France: a populist, grassroots protest movement – led by workers – for economic justice. While The War of the Poor is about 16th-century Europe, this short polemic has a lot to say about inequality now.

Have you read anything on this longlist?

But the novel isn’t about politics, it concerns a few players and characters, who we are given glimpses of, in a style that is like a series of snapshots, a narrative that therefore has gaps and not the fluidity of a traditional story, nor enables us to really get to know too well the characters, limited as we are by this kaleidoscopic technique.

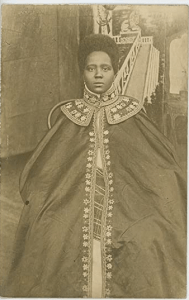

But the novel isn’t about politics, it concerns a few players and characters, who we are given glimpses of, in a style that is like a series of snapshots, a narrative that therefore has gaps and not the fluidity of a traditional story, nor enables us to really get to know too well the characters, limited as we are by this kaleidoscopic technique. One evening they listen to the radio and hear the (now) famous words of Empress Menen of Ethiopia disclosing the aggression to the World Women’s League, appealing to all world nations:

One evening they listen to the radio and hear the (now) famous words of Empress Menen of Ethiopia disclosing the aggression to the World Women’s League, appealing to all world nations: Though she uses her imagination, it is historical fiction after all, this is not a fantasy or adventure, and the role these women took on and the sacrifices and risks they took in doing so, meant they were heroines not in the traditional masculine sense, but that they showed solidarity towards keeping these invaders away and presented an image of provocation and strength, one that no European army, likely had ever seen.

Though she uses her imagination, it is historical fiction after all, this is not a fantasy or adventure, and the role these women took on and the sacrifices and risks they took in doing so, meant they were heroines not in the traditional masculine sense, but that they showed solidarity towards keeping these invaders away and presented an image of provocation and strength, one that no European army, likely had ever seen.

Jas lives with her devout farming family in the rural Netherlands. One winter’s day, her older brother joins an ice skating trip. Resentful at being left alone, she makes a perverse plea to God; he never returns. As grief overwhelms the farm, Jas succumbs to a vortex of increasingly disturbing fantasies, watching her family disintegrate into a darkness that threatens to derail them all.

Jas lives with her devout farming family in the rural Netherlands. One winter’s day, her older brother joins an ice skating trip. Resentful at being left alone, she makes a perverse plea to God; he never returns. As grief overwhelms the farm, Jas succumbs to a vortex of increasingly disturbing fantasies, watching her family disintegrate into a darkness that threatens to derail them all. Listening to the author read in Dutch was wonderful and the discussion between the judge, the translator and author worth listening to and may well influence more to discover what the book is about.

Listening to the author read in Dutch was wonderful and the discussion between the judge, the translator and author worth listening to and may well influence more to discover what the book is about. Auē has just won the annual

Auē has just won the annual

Ari befriends the neighbours daughter Beth, she lives with her Dad and Ari prefers the atmosphere over there, even though some of the things Beth likes scare him. Beth is brilliant, a little kid with a whole lot of attitude, the confidence of being reassuring well-loved, if dangerously naive due to a little parental inattentiveness. And those drop-dead, three words she utters that steal or perhaps save the narrative.

Ari befriends the neighbours daughter Beth, she lives with her Dad and Ari prefers the atmosphere over there, even though some of the things Beth likes scare him. Beth is brilliant, a little kid with a whole lot of attitude, the confidence of being reassuring well-loved, if dangerously naive due to a little parental inattentiveness. And those drop-dead, three words she utters that steal or perhaps save the narrative.

It is an interesting concept and a thrilling journey, one of the most moving and real parts for me being an encounter with an anaconda that almost had fatal consequences. However, throughout the book, I couldn’t shake off a sense of reluctance, of characters holding back; was Mr Fox being honest or was he hiding something? Why doesn’t Marina question or insist on answers? It was hard to believe that the head of a large pharmaceutical pouring significant funding into a research project would tolerate the situation without acting in a more forthright manner.

It is an interesting concept and a thrilling journey, one of the most moving and real parts for me being an encounter with an anaconda that almost had fatal consequences. However, throughout the book, I couldn’t shake off a sense of reluctance, of characters holding back; was Mr Fox being honest or was he hiding something? Why doesn’t Marina question or insist on answers? It was hard to believe that the head of a large pharmaceutical pouring significant funding into a research project would tolerate the situation without acting in a more forthright manner. The film is based on the true story of a 7-year-old boy kidnapped by Indians, who disappear into the Amazon forest. The boy’s father, a Venezuelan engineer, spent every summer for the next 10 years searching the forests for his son and eventually found him.

The film is based on the true story of a 7-year-old boy kidnapped by Indians, who disappear into the Amazon forest. The boy’s father, a Venezuelan engineer, spent every summer for the next 10 years searching the forests for his son and eventually found him.