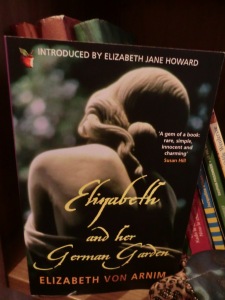

Staying overnight with friends in England just before Christmas, this book by Elizabeth von Arnim was placed on my bedside table and though there was no chance I would finish it, I was captivated and charmed by Elizabeth’s garden right from those first few pages.

Staying overnight with friends in England just before Christmas, this book by Elizabeth von Arnim was placed on my bedside table and though there was no chance I would finish it, I was captivated and charmed by Elizabeth’s garden right from those first few pages.

May 7th – I love my garden. I am writing in it now in the late afternoon loveliness, much interrupted by the mosquitoes and the temptation to look at all the glories of the new green leaves washed half an hour ago in a cold shower. Two owls are perched near me, and are carrying on a long conversation that I enjoy as much as any warbling of nightingales. The gentleman owl says

, and she answers from her tree a little way off,

, beautifully assenting to and completing her lord’s remark, as becomes a properly constructed German she-owl. They say the same thing over and over again so emphatically that I think it must be something nasty about me; but I shall not let myself become frightened away by the sarcasm of owls.

I left without the book, only for it to land on my doorstep late January on my birthday, and in these cold harsh months when the comforts of a garden are not so easy to find, when I have been finding solace instead in the nature essays of Kathleen Jamie and the short stories of Tove Jansson (review to come), this novel was a welcome respite.

It is fiction, though reads very much like an autobiography and was initially published anonymously in 1898. The author (a cousin of Katherine Mansfield) is said to have been born in Sydney, in NZ and in England, I’m not sure about any of that, but her parents did leave Sydney and return to England where she was raised (while her father’s brother and family remained in New Zealand).

It seems likely that Katherine Mansfield spent time with these relations when she moved to England herself, I found one reference confirming this, a comment by the journalist (and relation of the two) Louise Ahearn, who is currently researching Elizabeth’s life and it is mentioned in the book that Katherine visited her cousin at the home she built Chateau Soleil, in Switzerland.

On a tour of Europe, while in Rome with her father when she was 23-years-old, her talented piano playing was overheard by Il Conte the German Graf Henning August von-Armin-Schlagenthin, who was travelling to help get over the death of his wife and child the previous year. After a persistent courtship they were married and soon settled into upper-class life in Berlin, where she gave birth to three girls in quick succession.

Not happy in Berlin and homesick for England, in 1896 she was introduced to the family estate Nassenheide, ninety miles north of Berlin in Pomerania. A seventeenth century-schloss, located at the time near the German border (now in Poland), it had been a convent and had not been lived in for more than 25 years, surrounded by an unkempt, rambling, derelict garden which Elizabeth immediately fell in love with. She insisted on living there and it seems she got her way (at least for the summer months), much to the chagrin of her husband, whom she affectionately refers to in the novel as the Man of Wrath.

The book captures many moments of appreciation of this unorthodox wilderness the character Elizabeth is so content within, and equal moments of candour at the annoyance of those who dare impose themselves to visit. She has difficulty keeping the gardener who often hands in his notice while she somehow convinces him to stay, until events dictate that drastic action is necessary to get rid of him.

The gardener has been here a year and has given me notice regularly on the first of every month, but up to now has been induced to stay on. On the first of this month he came as usual, and with determination written on every feature told me he intended to go in June, and that nothing should alter his decision. I don’t think he knows much about gardening, but he can at least dig and water, and some of the plants he plants grow, besides which he is the most unflaggingly industrious person I ever saw, and has the great merit of never appearing to take the faintest interest in what we do in the garden. So I have tried to keep him on, not knowing what the next one may be like, and when I asked him what he had to complain of and he replied “Nothing,” I could only conclude that he has a personal objection to me because of my eccentric preference for plants in groups rather than plants in lines. Perhaps, too, he does not like the extracts from gardening books I read to him sometimes when he is planting or sowing something new.

The author is at her best when describing her longing for the garden and the simple pleasure it brings her, though equally adept are her recounts of conversations with city ladies of her social standing, capturing their inability to comprehend that it is by her own choice that she spends so much time in this savage wilderness, they are convinced they must feel sorry for her and that she has been deposed there, belonging as they do to that breed of women who absolutely require the regular company of their peers and the invitations to social occasions, something Elizabeth does her best to avoid.

Content with the book, inspired by but lacking the garden, we instead take a drive and a stroll around a much closer abandoned ruin, appreciating its beauty among the weeds.