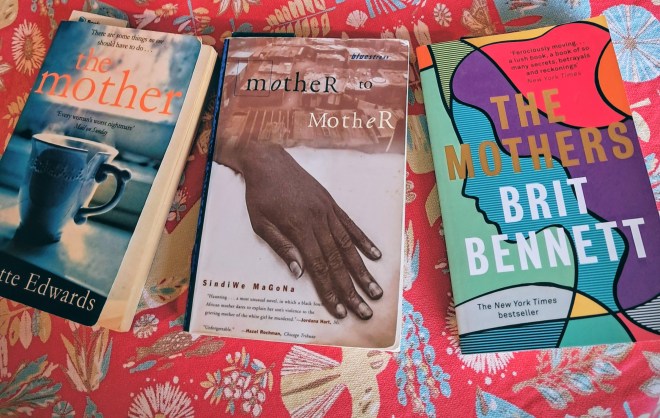

The third novel in my reading about mothers and motherhood is Brit Bennett’s The Mothers, the story of two young people, Nadia and Luke, who have both encountered significant turning points in their young lives, when they turn towards each other. Nadia, an only child, is mourning her mother, lost to suicide and Luke is nursing a football injury that has removed him from the limelight.

If Nadia Turner had asked, we would’ve told her to stay away from him.

Their coming together and drifting apart might have had less of an affect on their lives, had it not been for the teen pregnancy and cover-up that resulted from it, forever creating a fusion between them they have trouble negotiating, despite the years and distance they have put between them.

Her mother had died a month ago and she was drawn to anyone who wore their pain outwardly, the way she couldn’t.

Elder Knowledge and Wisdom

Luke is the son of a pastor and within that community are the older ‘Mothers‘, who provide the ‘We‘ voice to the narrative that isn’t always kind, it is the voice of those who have seen it all before.

We would’ve told her that all together, we got centuries on her. If we laid all our lives toes to heel, we were born before the Depression, the Civil War, even America itself. In all that living, we have known men,. Oh girl, we have known littlebit love. That littlebit of honey left in an empty jar that traps the sweetness in your mouth long enough to mask your hunger. We have run tongues over teeth to savor that last littlebit as long as we could, and in all our living, nothing has starved us more.

Though they don’t comment directly to Nadia or provide support to her, they are the all seeing, all knowing voice of the past, who also know that one has to live through their own experiences to learn anything, and so they enjoy their gossiping and smug knowledge of knowing how it will end before the living is done.

All good secrets have a taste before you tell them, and if we’d taken a moment to swish this one around our mouths, we might have noticed the sourness of an unripe secret, plucked too soon, stolen and passed around before its season. But we didn’t. We shared this sour secret, a secret that began when Nadia Turner got knocked up by the pastor’s son and went to the abortion clinic downtown to take care of it.

Nadia hides her secret from everyone, including her pious best friend Aubrey, the distance she puts between herself and her hometown, her foreign boyfriend and her higher education assist her in creating a new life far from unwanted memories.

Community Intentions

The Mothers meet regularly to pray. They read the prayer request cards and pray for the community who share their pain, their resentments, their anger and fears. And that too, is how they know all that is going on in their community, the clues that along with chatter create the jigsaw puzzle of lives that come and go among them.

That evening, we found a prayer card with his name on it in the wooden box outside the door. In the centre, in all lowercase, the words pray for her. We didn’t know which her he meant – his dead wife or his reckless daughter – so we prayed for both.

Youth Must Experience It

The novel follows the lives of the young people as they eventually confront the things they have tried to ignore, when they realise the impact they continue to have on them and slowly, the story behind the lost mother comes to light.

But she saw then that Nadia didn’t speak about her mother because she wanted to preserve her, keep her for herself. Aubrey didn’t speak about her mother because she wanted to forget that she’d ever had one.

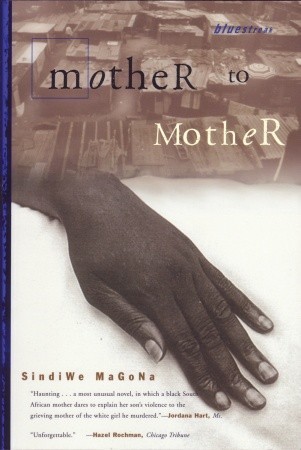

The Mothers is more reflective and less intense than the previous two novels I read, which concerned the death of a child, whereas here it is the loss of a mother and the loss of becoming a mother, and others for whom their mothers, though present, provide no solace at all. And the little spoken about loss of a potential father, a failure to perform one of the primary functions, to protect his family.

Each of the three stories shows communities as both supportive and punitive and mothers as complex products of their circumstances. Love is present, but so are disappointment, misunderstanding, judgement and the fear of not being enough. Silence too, becomes both a survival strategy and a cause of generational pain, broken through often by external friendships, safe spaces where women can express openly and move through their grievances towards healing.

I found The Mothers a thoughtful exploration of complex issues that youth encounter and then must live with and navigate and grow through. It shows the numerous ways people do that, sometimes in community, other times in isolation, but always seeking to find that peaceful place within which they can exist.

What is Brit Bennett Working On Now?

It has been a while since Brit Bennet’s second novel The Vanishing Half (2020), so I checked to see what she might be working on and learned that while there is no publication date yet, she is a ‘few drafts deep’ into a third novel, focused on R&B musicians, a girl group, about two singers who have a lifelong feud. It is said to deal with themes of rivalry, celebrity, and identity.

Author, Brit Bennett

Born and raised in Southern California, Brit Bennett earned her MFA in fiction at the University of Michigan.

Her debut novel The Mothers was a New York Times bestseller, and her second novel The Vanishing Half was an instant #1 New York Times bestseller. Her essays have been featured in The New Yorker, the New York Times Magazine, The Paris Review, and Jezebel.

Victoria Bennett was born in Oxfordshire in 1971. A poet and author, her writing has previously received a Northern Debut Award, a Northern Promise Award, the Andrew Waterhouse Award, and has been longlisted for the Penguin WriteNow programme and the inaugural Nan Shepherd Prize for under-represented voices.

Victoria Bennett was born in Oxfordshire in 1971. A poet and author, her writing has previously received a Northern Debut Award, a Northern Promise Award, the Andrew Waterhouse Award, and has been longlisted for the Penguin WriteNow programme and the inaugural Nan Shepherd Prize for under-represented voices.