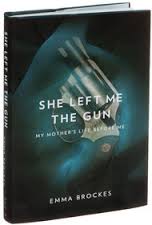

Four wives and an addiction to marriage. Despite the difficulty he had remaining faithful, Hemingway didn’t like being single, he liked his women to be contracted to him and then to have his liberty.

Though not a huge fan of his work, being more of a Steinbeck admirer than Hemingway, his connection to France and that group of Americans referred to as the lost generation, those who stayed or returned to Europe after the war, has ensured another kind of following and spawned an entire collection of literature, that which reimagines the lives of the artists, writers, their wives, mistresses and hangers-on. So I am one of those who enjoys reading more about him, than reading his actual work.

Thus far, I enjoyed meeting Hadley Richardson, Hemingway’s first wife through Paula McLain’s novel The Paris Wife, Zelda Fitzgerald, F.Scott Fitzgerald’s wife in Therese Anne Fowler’s Z: A Novel of Zelda and Gertrude Stein and others in Hemingway’s A Moveable Feast. He even made an appearance in Francisco Haghenbeck’s The Secret Book of Frida Kahlo while she was hanging out in Paris with Salvador Dali, Georgia O’Keefe and the Surrealists.

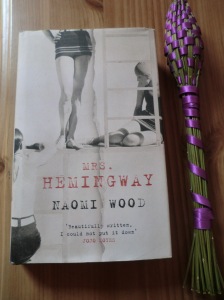

Naomi Wood joins the club of authors channelling the voices of expat writers wives who lived in Paris, fascinating not just because they were the wives of men who wrote famous stories, but because they are women who made the decision to abandon the comfortable and familiar, to leave their country and family behind.

Naomi Wood joins the club of authors channelling the voices of expat writers wives who lived in Paris, fascinating not just because they were the wives of men who wrote famous stories, but because they are women who made the decision to abandon the comfortable and familiar, to leave their country and family behind.

Both Hadley Richardson and Zelda Fitzgerald arrived in the shadow of their husbands dreams, without any ambition other than to be a faithful and supportive wife. As such, they encountered innumerable challenges in trying to create a satisfactory home life in a foreign country.

All of Hemingway’s wives spent time living in Paris, both the city and the man the thread that bound them together. Of the four, Martha and Mary perhaps fared better, both working journalists living there on their own terms, with their own purpose outside of marriage.

The book is structured in four equal parts, each dedicated to one wife and starts by portending the end, scenes that evoke the sense of an ending while they also contain the feminine distraction that signals the introduction of the next potential marriage candidate. Not one of the wives will be immune to the repetitive Hemingway pattern. It is a pattern he repeats all his life until the brutal ends.

With each end, we witness the beginning and each wife is witness to the new arrival and a foreshadowing of her demise. The novel centres around how he entered and exited these relationships without dwelling on the mundane, the structure keeping up the pace and instilling a sense of anticipation in the reader, wanting to know what could have happened in between times to change things.

“Sitting beside this woman to whom Ernest as already dedicated a poem, Martha recognizes Mary suddenly for what she is: her ticket out of here. This morning she saw that Ernest won’t let her break things off if there’s any chance he’s going to be alone. What he fears is loneliness, and whatever brutish thoughts he has when he is left untended. Only is he is assured of another wife will he let his present wife go.”

Like a poem, there is symmetry to the four wives and while they all love their husband and support him, none can prevent his inclination towards self-destruction, his propensity for excess. It is an insightful book in the way it presents the four relationships, carefully chosen scenes depicting the emergence and decline of their relationship.

We witness the relationships come and go like waves rising out of the ocean, resplendent at their peak, despite containing the knowledge of their inevitable destiny, to crash, disappear and reform anew. Hemingway rode the waves for as long as he could, writing prolifically, often using his own experiences as his subject matter. Perhaps he finally made it to the foreshore and saw the metaphoric waves for what they are, water rising and falling until it inevitably reaches the shore and destroys itself.

A worthy addition to the collection of literature that imagines the lives of Hemingway, his wives and the lost generation.

Her family, weathered by years of neglect, corruption and psychological torment, live in a claustrophobic environment that causes Andrea to develop her own eccentric behaviour in an effort to escape theirs. The house is inhabited by her two uncles, Juan and Roman, her aunt Angustias, the maid Antonia, and Juan’s wife, Gloria, plus a menagerie of cats, an old dog and a parrot.

Her family, weathered by years of neglect, corruption and psychological torment, live in a claustrophobic environment that causes Andrea to develop her own eccentric behaviour in an effort to escape theirs. The house is inhabited by her two uncles, Juan and Roman, her aunt Angustias, the maid Antonia, and Juan’s wife, Gloria, plus a menagerie of cats, an old dog and a parrot.