I first read Haitian author, Edwidge Danticat last summer, her novel Breath, Eyes, Memory (review linked below) about a young girl living with her Aunt in Haiti, while her mother lived in New York, a little like the life of the author herself, much of which is revealed in this non-fiction title, Brother, I’m Dying where we learn more about her life, though the primary focus is on her father Mira and in particular, her Uncle Joseph.

I first read Haitian author, Edwidge Danticat last summer, her novel Breath, Eyes, Memory (review linked below) about a young girl living with her Aunt in Haiti, while her mother lived in New York, a little like the life of the author herself, much of which is revealed in this non-fiction title, Brother, I’m Dying where we learn more about her life, though the primary focus is on her father Mira and in particular, her Uncle Joseph.

After having read a number of books in the Caribbean tradition recently, it is both unique and a gesture of deep reverence to read about the special connection between a daughter and her two fathers, for she sees both these men, and rightfully so, as her fathers.

The novel opens on the day of two discoveries, the author learns she is pregnant with her first child and hears that her father has been diagnosed with a terminal illness. The pulmonary disorder had required him to take medicine (containing codeine) resulting in his taxi licence being revoked. The medicine did nothing to alleviate his symptoms, worse it lost him his job and his dignity.

The chapters alternate between their present life in America and the author’s early life in Haiti, recounting the lives of the two brothers. We come to understand the lives they create from the choices they made, how they reinvent themselves, the obstacles they face, whether it’s family, work, the establishment, or navigating the political and legal demands of the countries they inhabit.

Mira leaves Haiti to create a better life in America for his family, a departure the author has no memory of, though her Uncle Joseph’s adopted daughter Marie Micheline shared stories with her, in a tradition common to people like her, anecdotes of poignant memories for those that have been left, to serve as reassurance that they were and are loved.

“Unfortunately I wasn’t told many stories like that. What I did often hear about was the future, an undetermined time when my father would send for my mother, Bob and me.”

Life was difficult for her mother and she often left the children with her brother-in-law to ensure the children had a decent meal. Then two years after her father left, when she was four and Bob was two, her mother’s visa was approved and she too departed, alone.

The two children became very attached to their Aunt and Uncle, while they waited out the nine long years before they too could make their eventual transition to join their parents in New York. Finally happening when Edwidge was twelve years old, it would be an even greater emotional challenge, not least because they had two younger brothers born in the US, one of whom believed he was the rightful, elder child of the family.

Back in Haiti, Joseph’s voice had begun to quiver, it worried him so he travelled to a hospital where US doctors were visiting, learning of a suspected tumour that would block his airways and suffocate him if not removed. It could be extracted in the US, but so too with it, would be his voice, reduced to a bare whisper, a death-knell for a pastor.

Almost like a miracle, on a subsequent visit for a check-up, he is shown a contraption he can use to amplify his whispers and allow people to hear him.

“My father took my uncle’s hand and led him to a lamp in a corner of the room, so he could better see the machine and its interaction with my uncle’s neck. This was their first two-sided conversation in many years and they both seemed to want to move it past the technicalities to a point of near normalcy.”

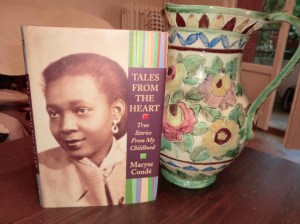

Edwidge Danticat

The one thing that remains constant throughout their long separation, is their love and respect for each other, as witnessed and shared through the eyes of their daughter and niece.

Edwidge Danticat writes in such an honest and compassionate way, you can’t help but become drawn into their story and feel concern at the various dramatic points that arise, willing things to turn out for the best – except that’s not what happens in real life – in reality, not everything will turn out as we will it to, but the memories will remain and the experiences contribute to forming the characters that we become.

It is a credit to the author to have chosen to share something of her life, her early childhood, without elevating herself as the main character of interest, it is both a story and a tribute to the extended family and the men who tried to lead them to live in safety.

The brothers chose different paths, one deciding to leave, the other to stay and though they were separated for 30 years their relationship remained strong, seeing each other as often as they could and keeping this strong connection between all the extended members of the family and their birth country.

As Cristina García, author of Dreaming in Cuban (one of my Top 5 Fiction Reads of 2015) put it:

“Edwidge Danticat’s moving tale of two remarkable brothers – her own father and her beloved Uncle Joseph, separated for thirty years – is as compelling and richly told as her fiction. Politically charged and sadly unforgettable, their stories will lodge themselves in your heart.”

A wonderful book, an honest portrayal of lives, where joy and struggle go hand in hand, where fear is never far from the front gate and sadness its companion, yet full of hope and spiritedness as an eighty-one-year old man refuses to let thugs take all that he has, and even though he risks his life, he will continue to pursue with righteousness, what is necessary in his own country to ensure justice. Which only serves to make what follows so immensely tragic.

A 5 star must read for me.

Further Links:

Skloot made Henrietta the subject of her research for 10 years in the creation of this thorough, respectful account of the life of Henrietta Lacks and her journey to uncover the events of the time within the context of what was the norm in her day.

Skloot made Henrietta the subject of her research for 10 years in the creation of this thorough, respectful account of the life of Henrietta Lacks and her journey to uncover the events of the time within the context of what was the norm in her day.

It is the 1980’s and one of the turning points in Lila’s deterioration is the earthquake that occurred on November 23, 1980 killing 3,000 and rendering 300,000 of Naples inhabitants homeless. It is used as a powerful metaphor for the destabilisation that occurs in Elena and Lila’s lives.

It is the 1980’s and one of the turning points in Lila’s deterioration is the earthquake that occurred on November 23, 1980 killing 3,000 and rendering 300,000 of Naples inhabitants homeless. It is used as a powerful metaphor for the destabilisation that occurs in Elena and Lila’s lives. Bride is young, in her twenties, but has learned early the importance of a word, a gesture, a look that can change people’s perception of you, as long as you stick to it, you become known for it, unforgettable, and that one thing can change your world.

Bride is young, in her twenties, but has learned early the importance of a word, a gesture, a look that can change people’s perception of you, as long as you stick to it, you become known for it, unforgettable, and that one thing can change your world.

Laila Lalami (US) – The Moor’s Account

Laila Lalami (US) – The Moor’s Account

The only reading experience I can compare this too is Orhan Pamuk’s The Museum of Innocence, which is a very long treatise on the experience of obsession, it is so long that you can’t help but experience the tedium of an unrelenting obsession.

The only reading experience I can compare this too is Orhan Pamuk’s The Museum of Innocence, which is a very long treatise on the experience of obsession, it is so long that you can’t help but experience the tedium of an unrelenting obsession.

The novel dwells on certain periods when members of the family return home, the four children are all adults in the opening pages and as the back story is filled in, we observe petty grievances, old resentments, current mysteries and a family coming to term with changes as their parents age and may need to move on from the family home.

The novel dwells on certain periods when members of the family return home, the four children are all adults in the opening pages and as the back story is filled in, we observe petty grievances, old resentments, current mysteries and a family coming to term with changes as their parents age and may need to move on from the family home.