For Reading Ireland Month 25, I am reading Sebastian Barry’s three novels that are part of the Dunne Family series. Here, I introduce the four works and review the first novel Annie Dunne.

Three novels and a play

Sebastian Barry wrote a series of four literary works about one strand of the fictional Dunne family (inspired in parts by his own ancestral lineage), who for seven generations were stewards of Humewood Estate, 470 acres of parkland and a castle in Kiltegan, County Wicklow.

Originally built in the 15th century, the property was sold by the last of that continuous line of family, Catherine Marie-Madeleine (Mimi) in 1992 and she would present most of the estate cottages to the sitting tenants. The castle is now owned by an American billionaire.

Barry says he did have some “inkling” that he might want to explore other family stories. “But I had absolutely no idea that 20 years later these people would still be with me. I’m in a book of quotations saying that, as our ancestors hide in our DNA, so do their stories. I don’t remember saying that, but over the years I’ve come to believe it. It’s as if these hidden people sometimes demand that their stories are told.” The Guardian

The Dunne Family Tetralogy

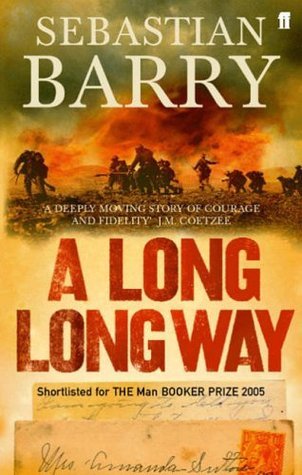

The play is about the first son Thomas, who did not become a steward, the next Annie Dunne (2002) is about one of his daughters Annie, then A Long Long Way (2005) is the story of his only son Willie Dunne, who joins the Dublin Fusiliers and goes to the Great War (WWI), and the final novel On Canaan’s Side (2011) is about Lily Bere (or Dolly as we know her), the youngest of the three sisters, who left Ireland for America.

Dunne Family #1 The Steward of Christendom

The play The Steward of Christendom (1995) centres around Thomas Dunne, the high-ranking, ex-chief superintendent of the Dublin Metropolitan police, looking back on his career built during the latter years of Queen Victoria’s empire, from his home in Baltinglass in Dublin in 1932.

He was Catholic, and loyally in service to both the British King, and his country (Ireland), however those twin loyalties collided in the period leading up to the Irish War of Independence (1919-1921), when he found himself on the ‘wrong’ side of history to his countrymen, culminating in a sense of failure, including the recurring memory of the handover of Dublin Castle to Michael Collins.

I haven’t read the play, but I know that he becomes a broken man, committed to an asylum, unable to reconcile what had happened, as if it were the downfall and undoing of himself, his family and lineage.

Dunne Family #2 Annie Dunne

Following the play, he wrote the novel Annie Dunne (2002), about the unmarried middle daughter of the superintendent, which takes place over one summer in her early sixties, when she is staying at her cousin Sarah’s cottage and small acreage in Kelsha, “a distant place, over the mountains from everywhere”, having found herself homeless after the premature death of her sister Maud and the downfall of her family.

Seven Generations of Caretakers, Coppicers, Caterers and a Cop

In the opening pages of Annie Dunne, we learn a little about that family history, the prestige of the line of stewards of Humewood Estate, the different direction her father took and his demise, having to put him in an asylum. The guilt over the end of her once regular visits, his lonely death.

Compared to her childhood in Dublin Castle and that long line of important roles that sheltered her, she too is now alone in these latter years, grateful to her cousin for taking her in. Their glory days behind them, she senses eyes on her without sympathy, in that way people regard someone perceived as having been superior, then find themselves without a safety net.

Those days are gone and blasted forever, like the old oak forests of Ireland felled by greedy merchants years ago.

A New Purpose, Another Marital Threat

When her sister Maud was dying, Annie tended her and the children. Now one of those boys is going to London with his wife, while his two children, four and six will stay under Annie’s care for the summer.

Words are spoken and I sense the great respect Sarah has for their father Trevor, my fine nephew, magnificent in his Bohemian green suit, his odd, English sounding name, his big read beard and his sleeked black hair like a Parisian intellectual, good-looking with deep brown angry eyes. He is handing her some notes of money, to help us bring the children through the summer. I am proud of her regard for him and proud of him, because in the old days of my sister’s madness I reared him.

Billy Kerr, a local man who does odd jobs, arrives unexpectedly early two mornings in a row to share a tea, Annie wonders why. And how her life became like this. The attention he gives Sarah unnerves her, “it is the air of the man”, and much of the novel delves into Annie’s inner world and outer efforts to secure her place.

At the mercy of influences outside her realm of control, she struggles to remain calm, and fears what she might be capable of. She must defend what she sees as her last refuge, her last stand.

Poor Annie Dunne, they must say, if they are kind. They will find other things to say, if they are not. Well, if we were something then, I am nothing now, as if to balance such magnificence with a handful of ashes.

A Strange Innocence, New Understanding

Annie is a complex character, she worries for the children, tries to care for them, observes behaviours that disturb her, jumps to conclusions, looks for support and doesn’t find it, fears herself and her reactions most of all. Her insecurities have made her paranoid, her need to blame risks falling on the innocent. Her desire to harm frightens her.

Her words are so simple, small, and low. Whispery. I feel myself the greater criminal by far than Billy Kerr. I should have kept my own opinions to myself, and let this story take its course, as I have always allowed every story that has come to me. She is open and raw to my wounds. That is why I have wounded her.

Taking place over that summer, the first half is rather mundane, the second half more dramatic as events occur that Annie is implicated in or threatened by, in which she takes some action, some thought out and calculated, other times over-reactive and hysterical. We wonder if she is becoming unravelled like her father, nothing is ever certain in a world that is constantly changing.

The summer comes to an end and none of them will be the same again; changed by their experience, further along in their understanding of themselves and others.

Even the halves of songs I know, our way of talking, our very work and ways of work, will be forgotten. Now I understand it has always been so, a fact which seemed to heal my father’s wound, and now my own.

I enjoyed the novel, but I admit I started it some time ago and set it aside, then went back to start again. It’s more of a winter read when you set more time to pushing through when a novel isn’t quite gripping you. The second time I started it felt very different and I had no trouble continuing on, but by then I also knew I was going to read all three and get the bigger picture.

There are issues in Annie Dunne that are not fully explored, and Annie represents that past characteristic of the Irish to knowingly suppress certain issues, lest it disturb their current situation, however over the course of the summer, she has transformed.

Further Reading

Article, The Guardian: ‘As our ancestors hide in our DNA, so do their stories’ by Nicholas Wroe, 2008

Article, The Atlantic: You Should Be Reading Sebastian Barry by Adam Begley

Read reviews of Annie Dunne by Kim at Reading Matters,

Author, Sebastian Barry

Sebastian Barry was born in Dublin in 1955. The 2018-2011 Laureate for Irish fiction, his novels have twice won the Costa Book of the Year award, the Independent Booksellers award and the Walter Scott Prize.

He had two consecutive novels shortlisted for the Booker Prize, A Long Long Way and The Secret Scripture and has also won the Kerry Group Irish Fiction Prize, the Irish Book Awards Novel of the Year and the James Tait Black Memorial Prize. He lives in County Wicklow.