Fourteen titles have been longlisted for the 8th annual award of the Warwick Prize for Women in Translation. The 2025 competition received a total of 145 eligible entries from 34 languages.

The longlist covers 10 languages, with Slovenian represented for the first time in the history of the prize.

The £1000 prize was established by the University of Warwick in 2017 to address the gender imbalance in translated literature and to increase the number of international women’s voices accessible by a British and Irish readership.

“For this award that considers all genres on equal terms, the judges have found longlist places not only for fiction of all sorts – from fiercely contemporary short stories to the epic debut by one of the 20th century’s greatest literary voices. We have selected searing memoir too, and (this year) an especially rich haul of poetry. The poetry books stretch from luminous snapshots of everyday experience to immersive mythic narrative in verse. Like our prose selections, they demonstrate the vision and artistry both of the original authors – and of the translators who carry this precious cargo across languages and cultures. Without them, our imaginative worlds would be so much smaller, and poorer.”

The 14 longlisted titles are:

And the Walls Became the World All Around, Johanna Ekström & Sigrid Rausing (Sweden)

translated from Swedish by Sigrid Rausing (Granta) (Biography/Memoir)

– Johanna Ekstrom was a Swedish artist and writer who published over a dozen books of poetry, fiction and memoir in her lifetime. In 2022, ill with cancer, she asked her closest friend, Sigrid Rausing, to edit and finish her final book. Originally a memoir on the loss of a relationship during the pandemic, the focus shifted from the loss of love to, potentially, the loss of life.

These excerpts from Ekstrom’s notebooks interwoven with Rausing’s reflections on the text and on their friendship are a testament to a voice and a life; a book made in grief over the loss of a close friendship of over thirty years.

Désirée Congo, Evelyne Trouillot (Haitian)

translated from French by M.A. Salvodon (University of Virginia Press)

– Désirée Congo is a riveting, powerful, original novel set in the final years of the Haitian Revolution. In this richly textured work, Trouillot constructs an intricate web from the varied experiences of freedmen and women, maroons, enslaved African people and their Creole children, as well as French planters and white smallholders in colonial Saint-Domingue at a historical moment of upheaval.

A lyrical book whose characters enrich our understanding of the last confrontations between Haitian revolutionaries and Napoleon’s imperial forces – a conflict that resulted in the success of the largest slave revolt in recorded history and the independence of the first Black state in the western hemisphere.

Djinns, Fatma Aydemir (Kurdish)

translated from German by Jon Cho-Polizzi (Peirene Press)

– For thirty years, Hüseyin has worked in Germany, taking every extra shift and carefully saving, providing for his wife and their four children. Finally, he has set aside enough to buy an apartment back in Istanbul – a new centre for the family and a place for him to retire. Just as this future is in reach, Hüseyin’s tired heart gives up. His family rush to him, travelling from Germany by plane and car, each of his children conflicted as they process their relationship with their parents, and each other.

Reminiscent of Bernardine Evaristo or Zadie Smith, Djinns portrays a family at the end of the 20th century in all its complexity: full of secrets, questions, silence and love.

The Empusium, Olga Tokarczuk (Poland)

translated from Polish by Antonia Lloyd-Jones (Fitzcarraldo Editions)

– In Sept 1913, Mieczysław Wojnicz, a student suffering from TB, arrives at Wilhelm Opitz’s Guesthouse for Gentlemen, a health resort in what is now western Poland. Every day, residents gather to imbibe the hallucinogenic local liqueur, to obsess over money, status and to discuss the great issues of the day: Will there be war? Monarchy or democracy? Do devils exist? Are women inherently inferior?

Meanwhile, disturbing things begin to happen around the guesthouse. As stories of shocking events in the nearby highlands reach them, a sense of dread builds. Someone, or something seems to be watching them and attempting to infiltrate their world. Little does Mieczysław realise, as he tries to unravel truths within himself and the mystery of the sinister forces beyond, that they’ve chosen their next target.

A century after the publication of The Magic Mountain, Olga Tokarczuk revisits Thomas Mann territory and lays claim to it, blending horror story, comedy, folklore and feminist parable with brilliant storytelling.

Francis Bacon’s Nanny, Maylis Besserie (France)

translated from French by Clíona Ní Ríordáin (The Lilliput Press)

– At the centre of the life of the great artists was an unexpected life-long influences Jessie Lightfoot shielded a young Francis Bacon from the brutish violence of his bullying father, as well as from his worst self-immolating excesses later in life. The tenderness, wit and warmth of this inimitable Nanny stands in illuminating relief to the sulphurous palette that defined Bacon’s work.

Beyond the humour and heart of an extraordinary woman confronted with the shade and guile of the art world, Maylis Besserie offers a glimpse of Ireland in the first half of the 20th C, a place apart from the rest of the world, whose landscapes, imagery and animals haunted the painter’s canvases.

In the final of Maylis Besserie’s trilogy, her focus on the art and lives of artists who crossed borders between France and Ireland closes as Bacon confronts boundaries between the real and the imagined.

Hungry for What, María Bastarós (Spain)

translated from Spanish by Kevin Gerry Dunn (Daunt Books Publishing)

– Violence and desire shatter the surface of the everyday in an exceptional collection of short stories.

A game between a woman’s father and husband simmers and boils into scalding danger; a daughter creates an elaborate feast for her grieving mother; a solar eclipse burns the emotions and truths of a suppressed neighbourhood into the open.

Foregrounding voices and experiences of women and children, veering from claustrophobic, suffocating suburbia to untamed nature and its great vistas of desert and sky, hungry for what focuses on the terror of normality, prising back its veneer of respectability to reveal the hostility & menace that seethe beneath.

Lies and Sorcery, Elsa Morante (Italy)

translated from Italian by Jenny McPhee (Penguin Press)

– For years Elisa has lived in an imaginary world of her own but when her guardian dies, young Elisa feels compelled to confront the truth of her family’s tortured and dramatic history by telling the story of her mother, Anna, and grandmother, Cesira. Elisa is a seductive, if less than reliable, spinner of stories, drawing the reader into a tale of intrigue, treachery and self-delusion, which is increasingly revealed to be an exploration of a legacy of political and social injustice.

First published in 1948, Elsa Morante’s novel won the Viareggio Prize & earned her the lasting admiration of writers such as Italo Calvino and Natalia Ginzburg.

My Secret Life, Krisztina Tóth (Hungary)

translated from Hungarian by George Szirtes (Bloodaxe Books)

– My Secret Life is the first book in English translation by one of the leading Hungarian poets of the generation who began publishing in the late 1980s. The poems in My Secret Life were selected from three of nine published collections, with the addition of some new or previously uncollected poems.

Phantom Pain Wings, Kim Hyesoon (South Korea)

translated from Korean by Don Mee Choi (And Other Stories)

– Winged ventriloquy – a powerful new poetry collection channelling the language of birds by one of South Korea’s innovative contemporary writers. An iconic figure in the emergence of feminist poetry in South Korea and now internationally renowned, Kim Hyesoon pushes the poetic envelope into the farthest reaches of the lyric universe. In her new collection, Kim depicts the memory of war trauma and the collective grief of parting through what she calls an “I-do-bird-sequence,” where “Bird-human is the ‘I.’”

Too Great A Sky, Liliana Corobca (Romania)

translated from Romanian by Monica Cure (Seven Stories Press UK)

– The story of the deportation of Romanians from Bukovina, an exercise in historical memory which demonstrates how to maintain humanity in impossible conditions.

Translation of the Route, Laura Wittner (Argentina)

translated from Spanish by Juana Adcock (Bloodaxe Books & Poetry Translation Centre)

– In poems that are precise, frank & finely tuned, award-winning Argentine poet Laura Wittner explores the specificities of parental and familial love, life after marriage, and the re-ignition of the self in middle age.

Un Amor, Sara Mesa (Spain)

translated from Spanish by Katie Whittemore (Peirene Press)

– Fleeing from past mistakes, Nat leaves her life in the city for the rural village of La Escapa. She rents a small house from a negligent landlord, adopts a dog and begins to work on her first literary translation. But nothing is easy: the dog is ill tempered and skittish and misunderstandings with her neighbour’s thrum below the surface. When conflict arises over repairs to her house, Nat receives an unusual offer that tests her sense of self, challenges her prejudices, and reveals her most unexpected desires. As she tries to understand her decision, the community of La Escapa comes together in search of a scapegoat.

Vanishing Points, Lucija Stupica (Slovenia)

translated from Slovenian by Andrej Peric (Arc Publications)

– Lucia Stupica’s 4th book of poetry comes after a decade of silence allowing her poetic voice to become more complex and sensitive to the cracks in time and in the world through which she observes fragments of life – imperfect, painful and real. Her expression retains its tenderness, establishing a deep dialogue with the world, the past and the present, with appearances and the things they conceal.

In an attempt at a new understanding of the world, Stupica writes of the role of women as the hidden movers of history, and the role of those, be they a man, a child or a random stranger, who see the experience of the other, and are open to it. These poems of love, loss, mystery and what lies beyond our understanding make for a haunting and memorable collection in Andrej Peric’s beautiful translation.

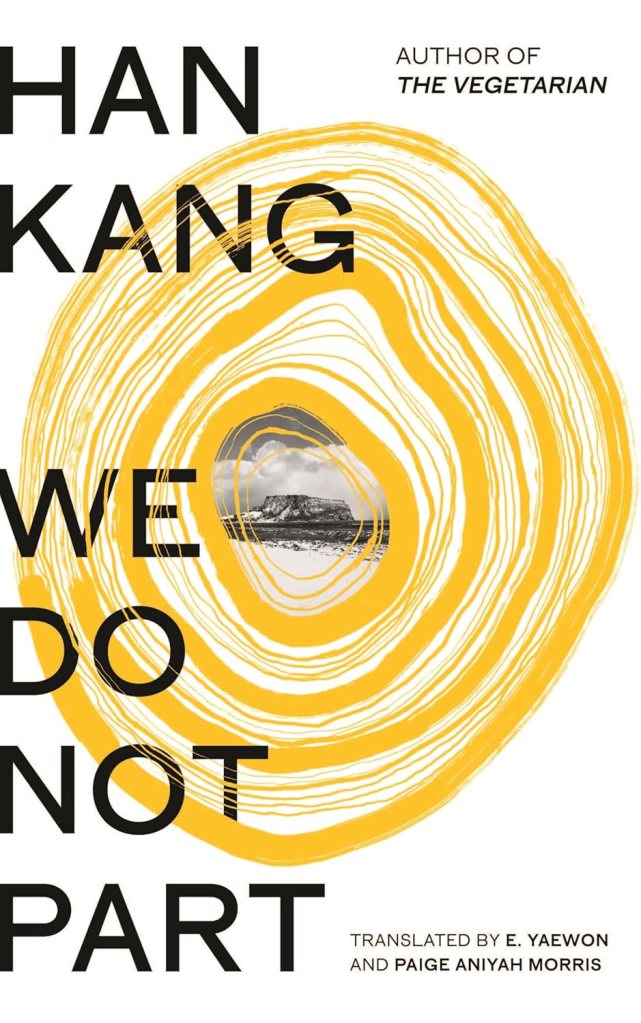

We Do Not Part, Han Kang (South Korea)

translated from Korean by e.yaewon & Paige Aniyah Morris (Hamish Hamilton, Penguin Random House UK)

– One morning in December, Kyungha is called to her friend Inseon’s hospital bedside. Airlifted to Seoul for an operation following a wood-chopping accident, Inseon is bedridden and begs Kyungha to take the first plane to her home on Jeju Island to feed her pet bird, who will quickly die unless it receives food.

As Kyungha arrives a snowstorm hits. Lost in a world of snow, she begins to wonder if she will arrive in time to save the bird – or even survive the terrible cold that envelops her with every step. She doesn’t yet suspect the darkness awaiting at her friend’s house.

There, the long-buried story of Inseon’s family surges into light, in dreams and memories passed from mother to daughter, and in a painstakingly assembled archive, documenting the terrible massacre 70 years before that saw 30,000 Jeju civilians murdered.

We Do Not Part is a hymn to friendship, a eulogy to the imagination, and above all a powerful indictment against forgetting.

* * * * * *

I have not read any of these titles, though I have read Han Kang’s extraordinary Human Acts, which this new novel reminds me of. Here the Novel Prize winning author asks similar questions of humanity. Another Nobel Prize winning author Olga Tokarczuk, has a new book here; I enjoyed Drive Your Plow Over the Bones of the Dead, but looking out for the less familiar, I’m interested in Kurdish author Fatma Aydemir‘s Djinns and another Italian classic author Elsa Morante looks tempting, despite the length.

Now that I’ve created the summaries, I can reread them at a leisurely pace in one location.

Any that interest you from this list?

The winner will be announced at a ceremony at The Shard in London on Thursday 27th November.

The children at school ask about her skin colour and ethnic origin.

The children at school ask about her skin colour and ethnic origin.

Sally Morgan is one of Australia’s best-known Aboriginal artists and writers.

Sally Morgan is one of Australia’s best-known Aboriginal artists and writers.

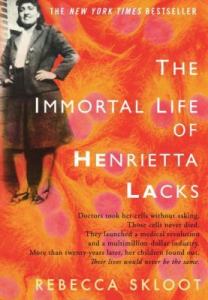

Skloot made Henrietta the subject of her research for 10 years in the creation of this thorough, respectful account of the life of Henrietta Lacks and her journey to uncover the events of the time within the context of what was the norm in her day.

Skloot made Henrietta the subject of her research for 10 years in the creation of this thorough, respectful account of the life of Henrietta Lacks and her journey to uncover the events of the time within the context of what was the norm in her day.