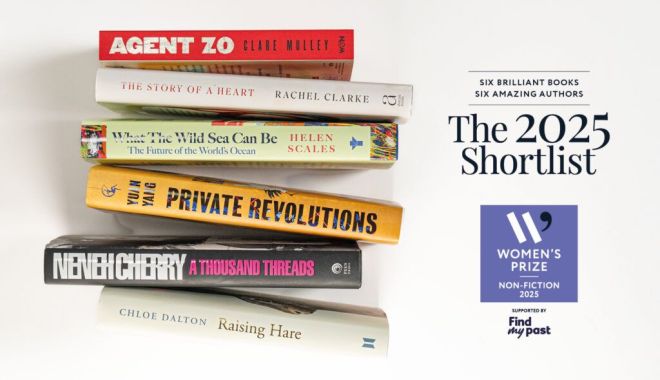

Now in it’s second year running, the Women’s Prize for Non-Fiction Shortlist has been announced. If you want a reminder, here are the 16 books that were on the longlist.

The six titles chosen range from history, science and nature, to current affairs and memoir, united by the power of hope and the necessity of resistance to initiate change.

Judge’s Comment

It’s an absolute pleasure to announce six books on our 2025 shortlist from across genres, that are united by an unforgettable voice, rigour, and unique insight. Included in our list are narratives that honour the natural world and its bond with humanity, meticulously researched stories of women challenging power, and books that illuminate complex subjects with authority, nuance and originality. These books will stay with you long after they have been read, for their outstanding prose, craftsmanship, and what they reveal about the human condition and our world. It was such a joy to embrace such an eclectic mix of narratives by such insightful women writers – we are thrilled and immensely proud of our final shortlist.

Kavita Puri, Chair of Judges

The Shortlist

Here are the six books chosen with a description, a short commentary by one of the judges and a link to a sample read or audio, if you’re interested to read/listen to a little of each title. Listening to the judges describe each book made them all sound really interesting to me.

I think I’m most interested by Agent Zo (after reading Madame Fourcade’s Secret War by Lynne Olson last year) and Private Revolutions because of its insight to another culture and those lives and stories that are so unlike our own. What do you think? Do any of these sound interesting to you?

Let me me know in the comments below.

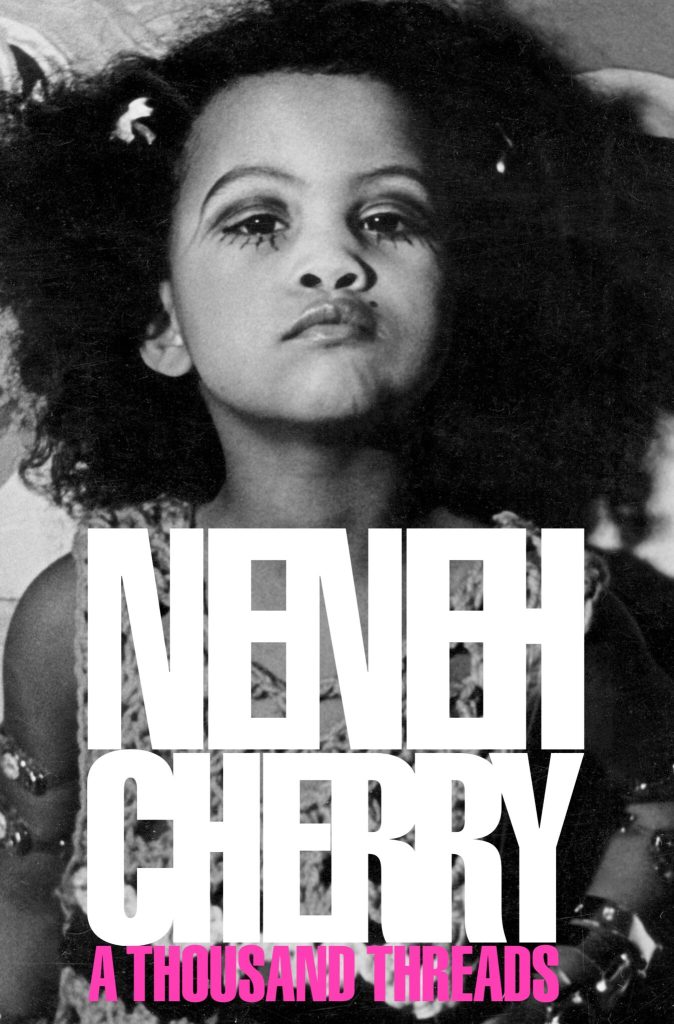

A Thousand Threads by Neneh Cherry (read a sample) (listen to audio)

Top of the Pops, December 1988. The world sat up as a young woman made her debut: gold bra, gold bomber jacket, and proudly, gloriously, seven months pregnant. This was no ordinary artist. This was Neneh Cherry.

But navigating fame and family wasn’t always simple. In this beautiful and deeply personal memoir, Cherry remembers the collaborations, the highs and lows, the friendships and loves, and the addictions and traumas that have shaped her as a woman and an artist. At the heart of it, always, is family: the extraordinary three generations of artists and musicians that are her inheritance and her legacy.

Musician. Songwriter. Collaborator. Activist. Mother. Daughter. Lover. Friend. Icon. This is her story.

A Thousand Threads by Neneh Cherry is the story of a remarkable life and the many threads that made it. Its about belonging, family, how we find our place in society, as well as music of course. The writing is exceptional and effortless. It’s a complex portrayal full of warmth, honesty and integrity and of how Neneh came to be who she is today.

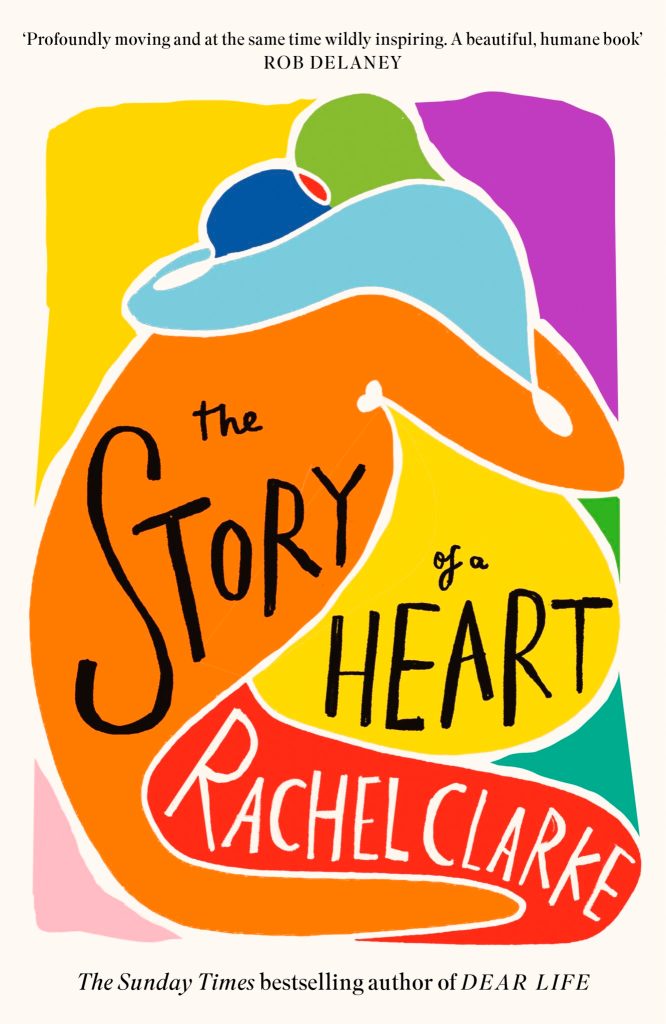

The Story of a Heart by Rachel Clarke (read a sample) (listen to audio)

The first of our organs to form, the last to die, the heart is both a simple pump and the symbol of all that makes us human: as long as it continues to beat, we hope.

One summer day, nine-year-old Keira suffered catastrophic injuries in a car accident. Though her brain and the rest of her body began to shut down, her heart continued to beat. In an act of extraordinary generosity, Keira’s parents and siblings agreed that she would have wanted to be an organ donor. Meanwhile nine-year-old Max had been hospitalised for nearly a year with a virus that was causing his young heart to fail. When Max’s parents received the call they had been hoping for, they knew it came at a terrible cost to another family.

This is the unforgettable story of how one family’s grief transformed into a lifesaving gift. With tremendous compassion and clarity, Dr Rachel Clarke relates the urgent journey of Keira’s heart and explores the history of the remarkable medical innovations that made it possible, stretching back over a century and involving the knowledge and dedication not just of surgeons but of countless physicians, immunologists, nurses and scientists.

The Story of a Heart is a testament to compassion for the dying, the many ways we honour our loved ones, and the tenacity of love.

The Story of a Heart by Rachel Clark is the tale of a boy, a girl and the heart they share. I like how the book combines the author’s expertise and the emotional resonance of the subject to bring together an extraordinary story. It moves effortlessly between disciplines and is meticulously researched and superbly written. I will find it impossible to forget.

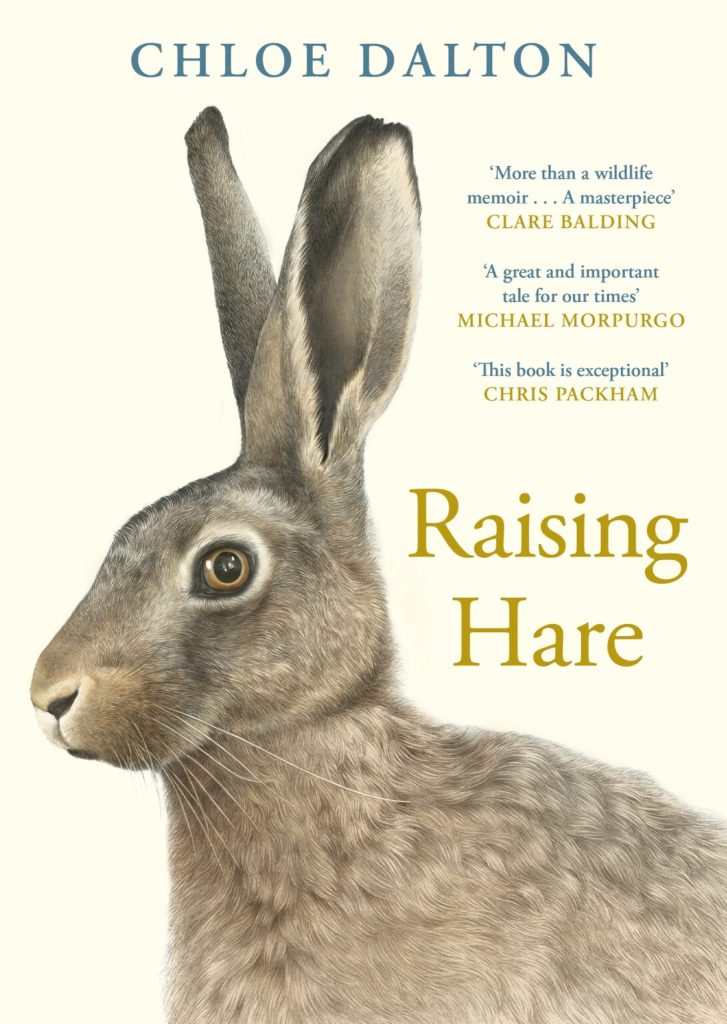

Raising Hare by Chloe Dalton (read a sample) (listen to audio)

Imagine you could hold a baby hare and bottle-feed it. Imagine that it lived under your roof and lolloped around your bedroom at night, drumming on the duvet cover when it wanted your attention. Imagine that, over two years later, it still ran in from the fields when you called it and snoozed in your house for hours on end. This happened to me.

When lockdown led busy professional Chloe to leave the city and return to the countryside of her childhood, she never expected to find herself custodian of a newly born hare. Yet when she finds the creature, endangered, alone and no bigger than her palm, she is compelled to give it a chance at survival.

Raising Hare chronicles their journey together and the challenges of caring for the leveret and preparing for its return to the wild. We witness an extraordinary relationship between human and animal, rekindling our sense of awe towards nature and wildlife. This improbable bond of trust serves to remind us that the most remarkable experiences, inspiring the most hope, often arise when we least expect them.

Raising Hare by Chloe Dalton is a beautiful meditation on the interactions between the human and the more than human that takes you under its spell. I really like how the book opens up questions of wildness, how do we let the wild into our lives, what can we do in our spaces to cultivate wild living? This is a captivating book that really stayed with me.

Agent Zo: The Untold Story of Courageous WW2 Resistance Fighter Elżbieta Zawacka by Clare Mulley (read a sample) (listen to audio)

This is the incredible story of Elzbieta Zawacka, the WW2 resistance fighter known as ‘Zo’. The only woman to reach London from Warsaw during the Second World War as an emissary of the Polish Home Army command, Zo undertook two missions in the capital before secret SOE training in the British countryside. As the only female member of the Polish elite Special Forces – the SOE-affiliated ‘Silent Unseen’ – Zo became the only woman to parachute from Britain to Nazi German-occupied Poland. There, whilst being hunted by the Gestapo who arrested her entire family, she took a leading role in the Warsaw Uprising and the liberation of Poland.

After the war she was demobbed as one of the most highly decorated women in Polish history. Yet the Soviet-backed post-war Communist regime not only imprisoned her, but also ensured that her remarkable story remained hidden for over forty years. Now, through new archival research and exclusive interviews with people who knew and fought alongside Zo, Clare Mulley brings this forgotten heroine back to life, and also transforms how we see the history of women’s agency in the Second World War.

Agent Zo: The Untold Story of Courageous WW2 Resistance Fighter Elżbieta Zawacka by Clare Mulley is a masterfully written biography that brings Elżbieta’s extraordinary story to life in exceptional detail. Phenomenally well researched, it’s a window into World War 2 stories that aren’t often heard, told through the life of an inspiring and powerful protagonist. I loved how the book follows Elżbieta right into the twenty-first century, showing the complexity of post-war politics. This is a history that still resonates today.

What the Wild Sea Can Be: The Future of the World’s Ocean by Helen Scales (read a sample) (listen to audio)

No matter where we live, ‘we are all ocean people,’ Helen Scales observes in her bracing yet hopeful exploration of the future of the ocean. Beginning with its fascinating deep history, Scales links past to present to show how prehistoric ocean ecology holds lessons for the ocean of today.

In elegant, evocative prose, she takes us into the realms of animals that epitomize current increasingly challenging conditions, from emperor penguins to sharks and orcas. Yet despite these threats, many hopeful signs remain, in the form of highly protected reserves, the regeneration of seagrass meadows and giant kelp forests and efforts to protect coral reefs.

Offering innovative ideas for protecting coastlines and cleaning the toxic seas, Scales insists we need more ethical and sustainable fisheries and must prevent the other existential threat of deep-sea mining. Inspiring us all to maintain a sense of awe and wonder at the majesty beneath the waves, she urges us to fight for the better future that still exists for the ocean.

A heartfelt exploration of the deep sea from coral to whales to emperor penguins to kelp, the writing is urgent and spellbinding and gripping, showing how humans have accelerated climate change and how we can fight for a better future. I absolutely loved spending time with the marine biologist Helen Scales down in the brutal and beautiful depths of the ocean.

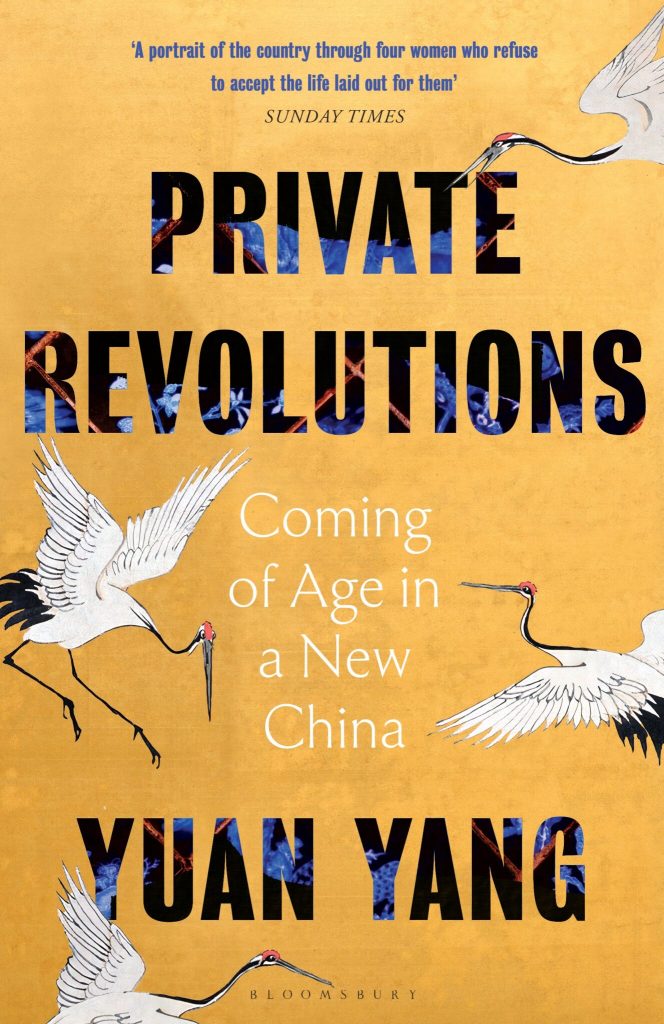

Private Revolutions: Coming of Age in a New China by Yuan Yang (read a sample) (listen to audio)

Yuan Yang, the first Chinese-born British MP, tells the stories of four Chinese women striving for a better future in an unequal society.

From June, who dreams of going to university rather than raising pigs, to Sam, forced into hiding as her activist peers are lifted from the streets, this is a singularly immersive portrait of a rapidly changing nation – and of the courage of those caught in the swell.

Private Revolutions: Coming of Age in a New China by Yuan Yang traces a moment of transition in China through the lives of four women who were growing up in the years after Tiananmen Square.These coming-of-age stories are ones you rarely hear of; individuals who want different lives from their parents who are battling the system.It’s eye-opening, beautifully written and carefully researched.

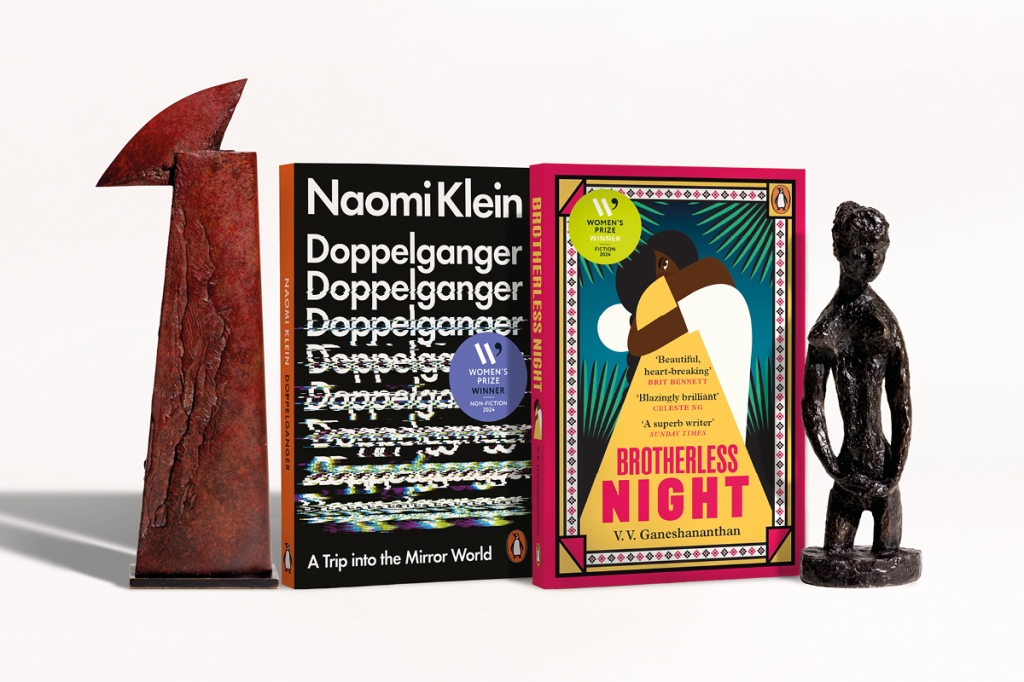

The Winner

The winner of the Women’s Prize for Non-Fiction will be announced on 12 June 2025, the same day as the winner for the Women’s Prize for Fiction, whose longlist you can view here. That shortlist will be announced on 2 April.