A Story of Tangled Love and Family Secrets

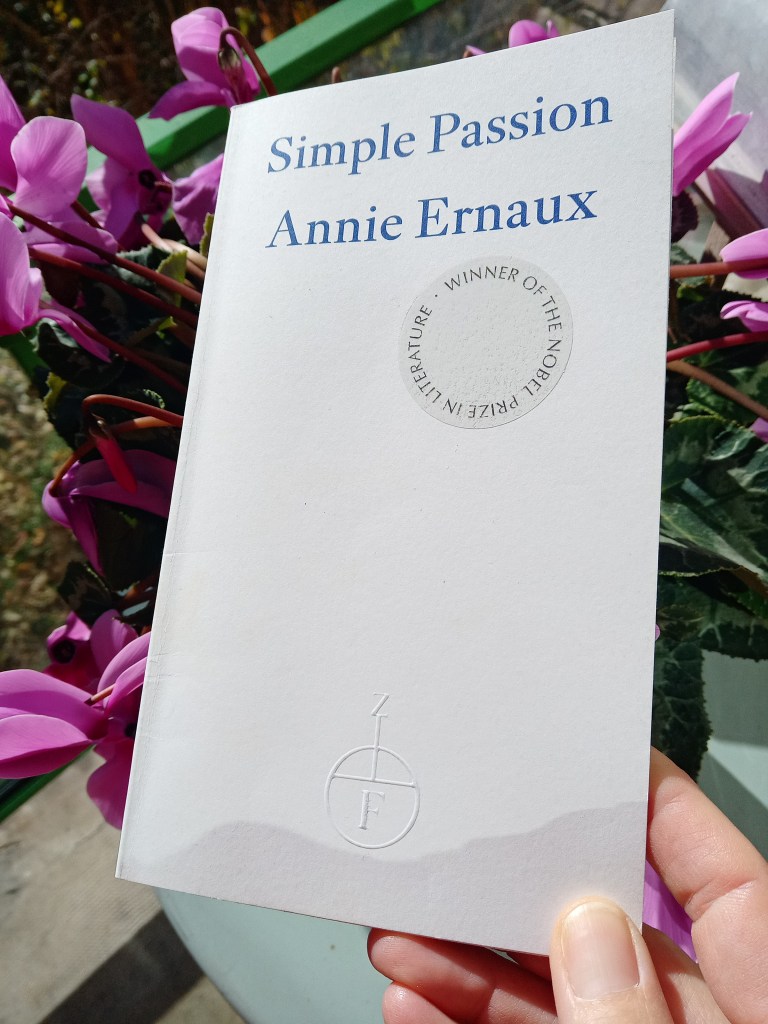

“But what is the point of writing if not to unearth things… Annie Ernaux

I chose to read Unearthing because it was the overall favourite read of 2023 of Shagafta who I follow on Substack and because it ties in to a theme I have been researching, exploring separation, kinship and the discovery of one’s identity.

Of Changing Seasons and Evolving Stories

Unearthing is a memoir of twenty four sekki (節気) or “small seasons” that offers a different way of thinking about the ever changing ground of our personal stories.

Three months after Kyo Maclear’s father dies, looking to know him at a deeper level and curious about his mother’s side of the family, she takes a DNA test.

When my father died and I was his grieving and wondering daughter, I thought of a word. The word, yugen, or what the Japanese call a state of “dim” or “deep” mystery, evokes the unsettled feeling I had at various points growing up as an only child. Our family was a tiny unit with strange ways. My parents acted like criminals on the lam – loading up moving vans, changing house every few years. I was four years old when we left England, shedding backstory and friends overnight. What made a family behave this way, like people drawn to erasure? Why were we always leaving like this, unceremoniously? I did not know. Growing up, I assumed that everyone was shaped and suffused by what they could not perceive clearly, the invisible and voiceless things imparted atmospherically within families.

Ask Your Father

Shocked, when she receives the results she learns that she is not biologically related to her father and that her mother refuses to speak on the subject.

She repeated it three times. Talk to your Dad. As if his death had been a hoax; her voice no longer blurry but brisk with fear.

Though her mother does not wish to talk about it, her daughter perseveres. She will weather this storm, waiting for it to calm, listening between the lines of conversation, picking up on the cues.

When one person leaves, the old order collapses. That’s why we were speaking to each other carefully. We were a shapeshifting family, in the midst of recomposing ourselves. What is grief, if not the act of persisting and reconstituting oneself? What is its difficulty, if not the pressure to appear, once more, fully formed?

Solving the Mystery of Your Life

Becoming a detective in her own life, Kyo assembles the story of her lineage, tied to the seasons and the making of a garden.

Digging was my way out. An impulse born of stubbornness and bred in me by a culture that loves stories of people discovering the truth of their paternity; that champions the idea that concealment is destructive and truth is freeing.

The way the Kyo Maclear takes her time unveiling the truth of her story, the various paths she follows, the thoroughness of her pursuit to know, makes this a thrilling read.

There is something about the long, slow seasons and the process of tending the soil, not trying to rush the end result that resonates in her writing, yet never slows the narrative.

Her observations of her mother, the nuanced noticing, are so well depicted, you can feel the resolution of the mystery getting warmer and warmer, as she regains her mother’s trust and nurtures her into revealing more.

Something

It was all being pulled from some shadowy room. The details she remembered. The broken chain of events. What she spoke arrived in fragments. But there was something else, a hitch and hesitance, that made me alert.

I did not yet understand the need to hold on to an invented story, even a falsified past, at all costs. I did not recognize her dissembling. Usually impervious, I thought she seemed out of sorts. Maybe a little distraught.

She does not want to tell me something, I thought.

Along the way larger questions arise: What exactly is kinship? What does it mean to be family? What gets planted and nurtured? What gets buried and forgotten? Can tending a garden heal anything?

I thought this memoir was brilliant, I highlighted so many thoughtful and thought provoking passages. I admired the way the revelations came slowly and the characters of her family were explored, her search for herself made her realise how little she knew of her own parents. They too, were a mystery to unravel and motivations to explore, before even embarking on the second exploration, the unknown aspect that her DNA revealed.

It also celebrates those that helped, guided and accepted her along the way, new relationships and a deeper understanding of aspects of the self, while never losing her essence.

Highly Recommended.

Kyo Maclear, Author

Kyo Maclear was born in London, England, and moved to Toronto at the age of four. She holds a doctorate from York University in Environmental Humanities.

Her most recent book, the hybrid memoir, Birds Art Life, was published in seven territories and became a Canadian #1 bestseller. It was a finalist for the Hilary Weston Writers’ Trust Prize for Nonfiction and winner of the Trillium Book Award.

Unearthing was an instant bestseller in Canada and winner of the Governor General’s Literary Award for Nonfiction. Her short fiction, essays, and art criticism have been published in Orion Magazine, Asia Art Pacific, LitHub, Brick, The Millions, The Guardian, Lion’s Roar, The Globe and Mail (Toronto) and elsewhere. She has been a national arts reviewer for Canadian Art and a monthly arts columnist for Toronto Life. She is also a children’s author, editor, and teacher.

She lives in Tkaronto/Toronto, on the traditional territories of the Mississaugas of the New Credit, the Haudenosaunee, Métis, and the Huron-Wendat.

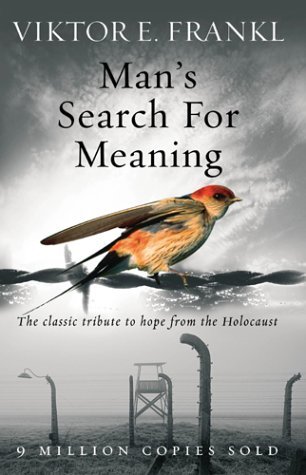

My friend then mentioned Viktor Frankl and interestingly, I learned he held a similar premise, but in the opposite direction. In terms of looking forward in life, we are likely to be more at peace and less prone to suffering if we have a ‘why’ in terms of our life’s meaning. So having our own ‘why’ is what we can focus on, looking forward, not back, at ourselves and not ‘the other’.

My friend then mentioned Viktor Frankl and interestingly, I learned he held a similar premise, but in the opposite direction. In terms of looking forward in life, we are likely to be more at peace and less prone to suffering if we have a ‘why’ in terms of our life’s meaning. So having our own ‘why’ is what we can focus on, looking forward, not back, at ourselves and not ‘the other’.

Viktor Emil Frankl, psychiatrist, was born March 26, 1905 and died September 2, 1997, in Vienna, Austria. He was influenced during his early life by Sigmund Freud and Alfred Adler, and earned a medical degree from the University of Vienna Medical School in 1930.

Viktor Emil Frankl, psychiatrist, was born March 26, 1905 and died September 2, 1997, in Vienna, Austria. He was influenced during his early life by Sigmund Freud and Alfred Adler, and earned a medical degree from the University of Vienna Medical School in 1930. Isabelle Allende looks back over her life from the viewpoint of her gender, as a woman and looks at how the family she was born into, and their circumstances contributed to her own growth and development and attitudes.

Isabelle Allende looks back over her life from the viewpoint of her gender, as a woman and looks at how the family she was born into, and their circumstances contributed to her own growth and development and attitudes.

Being in the later years of her life, she also reflects on that era, on the post retirement years and her attitude towards them, how she sees that she has changed, what she is and isn’t prepared to compromise on.

Being in the later years of her life, she also reflects on that era, on the post retirement years and her attitude towards them, how she sees that she has changed, what she is and isn’t prepared to compromise on. I thought it was brilliant and I Am as much in awe of how it’s been put together, as I Am of the insights she shares as each brush has its impact and adds to her knowledge of the body, mind and her own purpose in being here.

I thought it was brilliant and I Am as much in awe of how it’s been put together, as I Am of the insights she shares as each brush has its impact and adds to her knowledge of the body, mind and her own purpose in being here.

Short vignettes as Zadie Smith observes this particular moment in history passing, as she prepares to become one of those who returns, fleeing, always listening and observing others, sometimes in accordance with their uttered thoughts, at other times thinking she was, only to encounter her own subconscious bias.

Short vignettes as Zadie Smith observes this particular moment in history passing, as she prepares to become one of those who returns, fleeing, always listening and observing others, sometimes in accordance with their uttered thoughts, at other times thinking she was, only to encounter her own subconscious bias.

I was a little concerned by her reading habit in A Man With Strong Hands, though an avid reader myself, there are some times and places when it might be better to put the book down and allow the mind to rest, for this self-care activity she indulges, is one the few that allows one’s existential angst to cease, if only momentarily, for that weekly half hour she regularly gifts herself.

I was a little concerned by her reading habit in A Man With Strong Hands, though an avid reader myself, there are some times and places when it might be better to put the book down and allow the mind to rest, for this self-care activity she indulges, is one the few that allows one’s existential angst to cease, if only momentarily, for that weekly half hour she regularly gifts herself. Usually when I come across a new book that sounds like my kind of read, meaning it is of cross-cultural interest, where a character (or person) from one culture (preferably not one I’m familiar with) encounters another, I’ll find others who’ve read it to discern whether it’s for me or not.

Usually when I come across a new book that sounds like my kind of read, meaning it is of cross-cultural interest, where a character (or person) from one culture (preferably not one I’m familiar with) encounters another, I’ll find others who’ve read it to discern whether it’s for me or not.

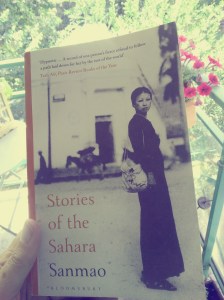

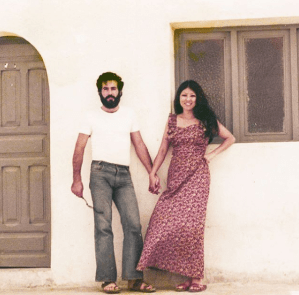

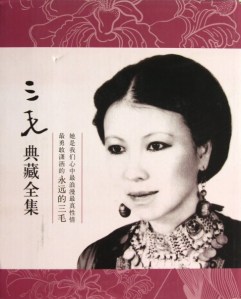

I absolutely loved Stories of the Sahara, in its entirety and it will likely be my favourite nonfiction title of the year. It is so refreshing to read a travelogue by a woman from another culture and discover a writer beloved of Chinese and Taiwanese readers for decades.

I absolutely loved Stories of the Sahara, in its entirety and it will likely be my favourite nonfiction title of the year. It is so refreshing to read a travelogue by a woman from another culture and discover a writer beloved of Chinese and Taiwanese readers for decades. The combination of her naivete, determination and feminism – her refusal to be stopped from doing what she wants – create some of the most hilarious and alarming moments. Her kindness and frankness gain her entry inside the culture and landscape, providing insights few are capable of accessing. People trusted her – yes they often took advantage of her – but she was a willing participant. They provided rich literary material, clearly!

The combination of her naivete, determination and feminism – her refusal to be stopped from doing what she wants – create some of the most hilarious and alarming moments. Her kindness and frankness gain her entry inside the culture and landscape, providing insights few are capable of accessing. People trusted her – yes they often took advantage of her – but she was a willing participant. They provided rich literary material, clearly! I received a few messages from friends and family in New Zealand wishing me a Happy Mother’s Day, which was lovely and unexpected.

I received a few messages from friends and family in New Zealand wishing me a Happy Mother’s Day, which was lovely and unexpected.