The first book I read by Han Kang was Human Acts and it remains my favourite, a deeply affecting novel. Her novel The Vegetarian won the Booker International Prize 2016 and she has written another book translated into English, that I have not read The White Book (a lyrical, disquieting exploration of personal grief, written through the prism of the color white).

Of Language and Loss

In a classroom in Seoul, a young woman watches her Greek language teacher at the blackboard. She tries to speak but has lost her voice. Her teacher finds himself drawn to the silent woman, as day by day he is losing his sight.

The novel goes back in time, slowly uncovering their stories, occasionally revisiting the present, when they are in class, until finally near the end, there is a scene where they properly interact.

Greek Lessons was enjoyable, but it took me a while to figure out which characters (unnamed) were controlling the narrative at any one time, and that didn’t really become clear until quite a way into the book, when the Korean man who teaches Greek and who had lived in Germany for some time, began to interact with the mature woman student in his class, due to a minor accident and his need for help.

Yearning for the Unattainable

Both these characters are dealing with issues, the woman has just lost custody of her 6 year old child, due to an imbalance in power and wealth between the two parents. She was mute as a child and had a special relationship with language, which has lead to her unique desire to learn to read and write in Greek. She dwells in silence, sits and stares, or pounds the streets at night, walking off the frustration she is unable to express with words.

The Greek teacher is slowly losing his sight, a condition inherited from his father. He is aware that he needs to prepare himself for a future without sight.

He recalls a lost, unrequited love and the mistakes he made. His narrative is addressed to this woman who he knew from a young age. There are letters that recount his memories, as well as the discomfort of living in another culture and his desire to return to Korea without his parents. It took me a while to realise this was a different woman.

Ultimately I was a little disappointed, because it lacked the emotive drive that I had encountered before from Han Kang. There were flashes of it, but about halfway, I lost interest and stopped reading for a while. I am glad I persevered as I enjoyed the last 30% when the characters finally have a more intimate encounter and are brought out of themselves, but I was hoping for more, much earlier on.

Reading Print Improves Comprehension

I did wonder too if it might have been better for me to read the printed version, when the narrator is unclear, I can flick back and forth and take notes in a way that isn’t as easily done reading an ebook.

This perspective is supported by a recent study from the University of Valencia that found print reading could boost skills by six to eight times more than digital reading. I tend to agree that digital reading habits do not pay off nearly as much as print reading.

I picked it up now after reading that it was one of Tony’s Top 10 Reads of 2023 at Tony’s Reading List. He reads a ton of Japanese and Korean fiction, so this is a highly regarded accolade from him. I would recommend reading his review here for a more succinct account of the book. I see he read a library print version.

He finds echoes of The Vegetarian ‘with a protagonist turning her back on the world, unable to conform’ and ‘the poetic nature of The White Book, often slowing the reader down so they can reflect on what’s being said’ describing the reading experience as:

a slow-burning tale of wounded souls. Poignant and evocative, Greek Lessons has the writer making us feel her creations’ sadness, their every ache.

In a review for The Guardian, 11 Apr 2023, Em Strang acknowledged that the book wasn’t about characters or plot, so asked what was driving the craft, identifying a courageous risk the writer took.

One answer is that it’s language itself, and the dissolution of language, which is why in parts the narrative seems to almost dissolve.

If you’re interested in reading Greek Lessons, I do recommend reading the print version.

Author, Han Kang

Han Kang was born in 1970 in South Korea. A recipient of the Yi Sang Literary Award, the Today’s Young Artist Award, and the Manhae Prize for Literature, she is the author of The Vegetarian, winner of the International Booker Prize; Human Acts; and The White Book.

Further Reading

The Guardian Article: Greek Lessons by Han Kang review – loss forges an intimate connection by Em Strang, 11 Apr, 2023

The Guardian Article: Reading print improves comprehension far more than looking at digital text, say researchers by Ella Creamer, 15 Dec 2023

N.B. This book was an ARC (Advance Reader Copy) kindly provided by the publisher via NetGalley.

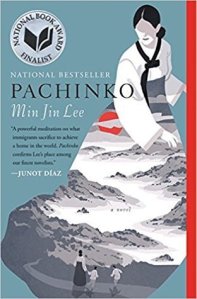

A New York Times Bestseller, Pachinko is a work of historical fiction set in Korea and Japan that follows the lives of one family and how their circumstances and choices continue to reverberate through the generations.

A New York Times Bestseller, Pachinko is a work of historical fiction set in Korea and Japan that follows the lives of one family and how their circumstances and choices continue to reverberate through the generations.

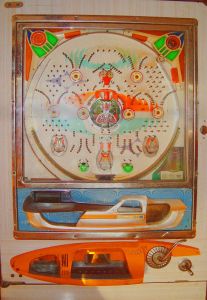

It is not until page 142 that we come across ‘pachinko’, the Japanese name for pinball, a huge industry in Japan at the entry into the workforce of Sunja’s son Mozasu.

It is not until page 142 that we come across ‘pachinko’, the Japanese name for pinball, a huge industry in Japan at the entry into the workforce of Sunja’s son Mozasu.