The International Booker Prize shortlist celebrated six novels in six languages (Dutch, German, Korean, Portuguese, Spanish and Swedish), from six countries (Argentina, Brazil, Germany, Netherlands, South Korea and Sweden), interweaving the intimate and political in radically original ways. All the books were translated into English and published in the UK/Ireland.

The shortlist was chosen from the longlist of 13 titles and today the winner was announced.

The Winner

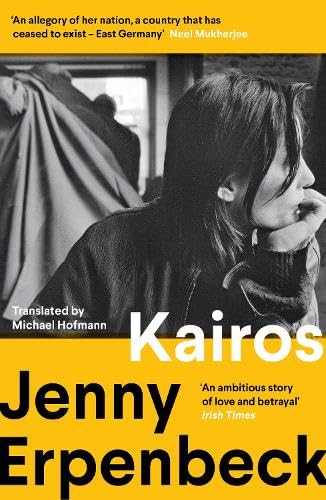

The winner for 2024 of the International Booker Prize is Kairos by Jenny Erpenbeck (Germany) translated from German by Michael Hofmann. Jenny Erpenbeck was born in East Berlin in 1967, and is an opera director, playwright and award-winning novelist.

Kairos is an intimate and devastating story of the path of two lovers through the ruins of a relationship, set against the backdrop of a seismic period in European history.

Berlin. 11 July 1986. They meet by chance on a bus. She is a young student, he is older and married. Theirs is an intense and sudden attraction, fuelled by a shared passion for music and art, and heightened by the secrecy they must maintain. But when she strays for a single night he cannot forgive her and a dangerous crack forms between them, opening up a space for cruelty, punishment and the exertion of power. And the world around them is changing too: as the GDR begins to crumble, so too do all the old certainties and the old loyalties, ushering in a new era whose great gains also involve profound loss.

What the International Booker Prize 2024 judges said

‘An expertly braided novel about the entanglement of personal and national transformations, set amid the tumult of 1980s Berlin.

Kairos unfolds around a chaotic affair between Katharina, a 19-year-old woman, and Hans, a 53-year-old writer in East Berlin.

Erpenbeck’s narrative prowess lies in her ability to show how momentous personal and historical turning points intersect, presented through exquisite prose that marries depth with clarity. She masterfully refracts generation-defining political developments through the lens of a devastating relationship, thus questioning the nature of destiny and agency.

Kairos is a bracing philosophical inquiry into time, choice, and the forces of history.’

Read An Extract From the Opening Chapter

Prologue

Will you come to my funeral?

She looks down at her coffee cup in front of her and says nothing.

Will you come to my funeral, he says again.

Why funeral— you’re alive, she says.

He asks her a third time: Will you come to my funeral?

Sure, she says, I’ll come to your funeral.

I’ve got a plot with a birch tree next to it.

Nice for you, she says.

Four months later, she’s in Pittsburgh when she gets news of his death.

Further Reading

Everything you need to know about Kairos

Q & A with Jenny Erpenbeck and Michael Hofmann

Thoughts

I haven’t read Kairos though it has had mainly positive reviews. I have read one of her novels Visitation some years ago and didn’t get on with that one too well, so I haven’t picked up any more of her work. I have no doubt that it is well written, I’m just not that interested in the premise.

Have you read Kairos? Or any other novels by Jenny Erpenbeck? Let us know in the comments below what you thought.

I found Visitation interesting the first time I read it, and much better the second time. I’m quite interested in the idea of Kairos, but not sure yet whether I’ll get round to reading it. I’m intrigued by writers from the former GDR and their take on life and experience, though.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I haven’t read it, maybe this is the push I need to give this writer a try. But the thing is, ‘relationship novels’ don’t interest me much. To put it another way, what’s the insight we gain from this book?

LikeLiked by 1 person

I can see why you might be put off by yet another relationship novel, Lisa, but it’s more an allegory exploring the history of the GDR, Erpenbeck’s native country which, of course, no longer exits. Highly recommend it.

LikeLiked by 3 people

I’ve read a few novels about the GDR: Deborah Levy’s The Man who Saw Everything; Siblings (1963), by Brigitte Reimann, translated by Lucy Jones; Kruso (2014), by Lutz Seiler, translated by Tess Lewis (which won the German Book Prize), and In Times of Fading Light (2011), by Eugen Ruge, translated by Anthea Bell (which I don’t recommend, it’s a bit of a mess IMO).

Plus also, two excellent TV series, The Weissensee Saga and Line of Separation.

And Stasiland by Anna Funder, of course.

So I reckon, for an Aussie on the other side of the world, I’m up to speed on the GDR, unless Erpenbeck has got something new to say about it. And from reading Natasha Walter’s review at The Guardian, it doesn’t look to me as if she does.

Which is not to say that it’s not a worthwhile book. There are no doubt plenty of readers who like relationship novels or who were born after the fall of the wall or are from cultures who know very little European history, who would find it very interesting. It’s just not for me.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I will leave that to the author to express, she said:

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks, Claire. An eloquent and enlightening quote.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I wasn’t planning on reading this one, I’ve read mixed reviews. But the extract from the Booker website was intriguing enough…maybe I will after all.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Sometimes we get swayed to read things that we had decided not to, by all the different writings and discussions and there’s always that element of, I can’t really comment because I haven’t read it; but despite this story being an allegory, I don’t wish to have to empathise with or immerse in the basic premise of an ‘older aware’ man having a relationship with a recent child, now ‘new young adult’ woman. As clever as it might be.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Kairos sounds compelling by your review and the opening chapter I will seek it out thank you

LikeLike

I’ve read and liked most of Erpenbeck’s work but I suspect I’m not the most objective reader, since I can relate so strongly to her biography (similar age and experience of growing up in a communist regime). I hesitated before reading this novel because I’d heard it was about a rather abusive relationship, but when I actually read it, it became so clear it is a metaphor for the political situation and it reminded me of so many things I’d pushed to the back of my mind.

So yes, it’s a worthy winner, although I personally thought Selva Almada should have won.

LikeLiked by 2 people

There is no way that there would not be an imbalance in power in such a relationship and regardless of the metaphor for the political situation, did the author really have to choose such an extreme disparity in the ages of her main protagonists to make the point?

LikeLike

I think it’s because she also wanted to show the difference in attitude between generations, between those who chose socialism (or at least benefited from it) and those who simply had to grow up with it. That is an acrimonious debate that is still raging in my country, with my own family for example.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m an admirer of Erpenbeck, both for this latest novel, and the only other one I’ve read – Go, Went, Gone. I’m interested in the way she invites thought on current political and social issues while delivering an involving and well-written story line.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh, yes, very good, and a deserving winner (from a mediocre list of books…).

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi there, while I found the central relationship rather hard to read-it becomes abusive- I do think the book gives a great insight into the last few years of the GDR. I’ve read a lot on this topic but never read such a devastating account of the humiliation of East Germans by the west in the process of reunification. This is the power of fiction and of this novel- you really feel it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I understand that metaphor for the humiliation of a people, but I question the use of such a young protagonist in relationship with such an inappropriate partner and my question is, could the point not have been made without such an extreme imagining, that is likely to titillate some while horrifying others?

LikeLike

I’m intrigued, but in a vague way. Still, I enjoy following the prizes and “discovering” (or “rediscovering”) new writers via their longlists (and, in this case, winners).

LikeLiked by 1 person