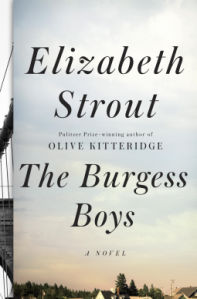

Like many readers, having enjoyed Olive Kitteridge, Strout’s previous book that won a Pulitzer Prize in 2009, I was looking forward to reading her next work. Rather than referencing Olive Kitteridge, which this book has very little in common with, The Burgess Boys arguably has more connections with Strout’s own life, growing up in small towns in Maine, studying law and moving to New York city.

Jim and Bob Burgess also have little in common except that they both studied law and moved to New York, one achieving notoriety, the other not. Their younger sister Susan never left Shirley Falls, Maine; they are now all late middle age, the trajectory of their lives influenced early on in childhood when Bob(4) and Jim(8) witnessed the death of their father as the car they were in, with their younger sister in the back, rolled forward down the family driveway and killed him.

Jim and Bob Burgess also have little in common except that they both studied law and moved to New York, one achieving notoriety, the other not. Their younger sister Susan never left Shirley Falls, Maine; they are now all late middle age, the trajectory of their lives influenced early on in childhood when Bob(4) and Jim(8) witnessed the death of their father as the car they were in, with their younger sister in the back, rolled forward down the family driveway and killed him.

Two thirds of his family had not escaped, this is what Bob thought. He and Susan – which included her kid – were doomed from the day their father died.

The two boys leave their hometown to pursue careers in New York city and have little to do with their sister, until a thoughtless act by her teenage son Zach, lands him in trouble with the police and the law and looks set to incite racial tension among the citizens of Shirley Falls and their Somali immigrant community.

He thought of all the people in the world who felt they’d been saved by a city. He was one of them. Whatever darkness leaked its way in, there were always lights on in different windows here, each light like a gentle touch on his shoulder saying, Whatever is happening, Bob Burgess, you are never alone.

Prior to the family drama Jim’s star was in the ascendant, he could do no wrong, however an indulged ego wins few favours long term and his good fortune risks changing course.

It is a story of family ties, separation, isolation, of fear and its consequence and the challenges of an evolving community, how newcomers don’t always bring out the best in their hosts, requiring as they do, new understanding and acceptance.

It was an uncomfortable start for me I admit, taking on a story that portrays a small town’s varying and little embracing of an immigrant community and the committing of a disrespectful act against it’s religious beliefs is fraught with danger in itself. Topical perhaps, but difficult to accurately or sufficiently portray balanced points of view.

Strout presents the family dilemma and while giving them an audible voice, keeps somewhat at a distance from the community Zach Burgess has upset, though at least she does not go so far as to incite the aggrieved community to inflame their response. But the story lacks something for having touched on a community in such an indignant way and failing to give them much of a voice, the one exception stretching the imagination in authenticity a little too far.

Strout presents the family dilemma and while giving them an audible voice, keeps somewhat at a distance from the community Zach Burgess has upset, though at least she does not go so far as to incite the aggrieved community to inflame their response. But the story lacks something for having touched on a community in such an indignant way and failing to give them much of a voice, the one exception stretching the imagination in authenticity a little too far.

Abdikarim, who had attended only because one of Haweeya’s sons came running to get him, saying his parents insisted he come to the park, had been puzzled by what he saw: so many people smiling at him. To look him straight in the face and smile felt to Abdikarim to display an intimacy he was not comfortable with. But he had been here long enough to know it was the way Americans were, like large children, and these large children in the park were very nice.

Not knowing much about Somali immigration to the US, I found these two articles helpful, particularly the former in it’s comparison between US and European immigrants.

What Makes Somali’s So Different? – an interesting article by Michael Scott Moore on the subject of Somali immigrants to the US.

A ray of hope – Somalia’s Future – an analysis by The Economist in Feb 2012 on the future within Somalia itself.

Note: This book was an Advance Reader Copy (ARC) provided kindly by the publisher via NetGalley.