The International Booker Prize shortlist celebrated six novels in six languages (Dutch, German, Korean, Portuguese, Spanish and Swedish), from six countries (Argentina, Brazil, Germany, Netherlands, South Korea and Sweden), interweaving the intimate and political in radically original ways. All the books were translated into English and published in the UK/Ireland.

The shortlist was chosen from the longlist of 13 titles and today the winner was announced.

The Winner

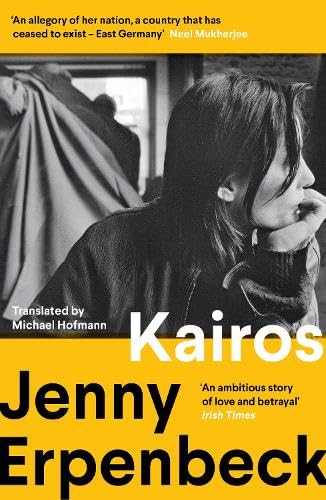

The winner for 2024 of the International Booker Prize is Kairos by Jenny Erpenbeck (Germany) translated from German by Michael Hofmann. Jenny Erpenbeck was born in East Berlin in 1967, and is an opera director, playwright and award-winning novelist.

Kairos is an intimate and devastating story of the path of two lovers through the ruins of a relationship, set against the backdrop of a seismic period in European history.

Berlin. 11 July 1986. They meet by chance on a bus. She is a young student, he is older and married. Theirs is an intense and sudden attraction, fuelled by a shared passion for music and art, and heightened by the secrecy they must maintain. But when she strays for a single night he cannot forgive her and a dangerous crack forms between them, opening up a space for cruelty, punishment and the exertion of power. And the world around them is changing too: as the GDR begins to crumble, so too do all the old certainties and the old loyalties, ushering in a new era whose great gains also involve profound loss.

What the International Booker Prize 2024 judges said

‘An expertly braided novel about the entanglement of personal and national transformations, set amid the tumult of 1980s Berlin.

Kairos unfolds around a chaotic affair between Katharina, a 19-year-old woman, and Hans, a 53-year-old writer in East Berlin.

Erpenbeck’s narrative prowess lies in her ability to show how momentous personal and historical turning points intersect, presented through exquisite prose that marries depth with clarity. She masterfully refracts generation-defining political developments through the lens of a devastating relationship, thus questioning the nature of destiny and agency.

Kairos is a bracing philosophical inquiry into time, choice, and the forces of history.’

Read An Extract From the Opening Chapter

Prologue

Will you come to my funeral?

She looks down at her coffee cup in front of her and says nothing.

Will you come to my funeral, he says again.

Why funeral— you’re alive, she says.

He asks her a third time: Will you come to my funeral?

Sure, she says, I’ll come to your funeral.

I’ve got a plot with a birch tree next to it.

Nice for you, she says.

Four months later, she’s in Pittsburgh when she gets news of his death.

Further Reading

Everything you need to know about Kairos

Q & A with Jenny Erpenbeck and Michael Hofmann

Thoughts

I haven’t read Kairos though it has had mainly positive reviews. I have read one of her novels Visitation some years ago and didn’t get on with that one too well, so I haven’t picked up any more of her work. I have no doubt that it is well written, I’m just not that interested in the premise.

Have you read Kairos? Or any other novels by Jenny Erpenbeck? Let us know in the comments below what you thought.

I’ve attempted to read Visitation about four times and never succeeded in getting past the first few chapters, but this year I persevered as I felt I hadn’t given it a fair chance.

I’ve attempted to read Visitation about four times and never succeeded in getting past the first few chapters, but this year I persevered as I felt I hadn’t given it a fair chance.