Brilliant.

A little way into reading, I had to pause and go back to the beginning, because this story is told not in a linear way, but in a spiral and with multiple perspectives that to me didn’t relate to what the blurb says this book is about.

A little way into reading, I had to pause and go back to the beginning, because this story is told not in a linear way, but in a spiral and with multiple perspectives that to me didn’t relate to what the blurb says this book is about.

Florens is the only voice we hear more than once as she sets out on her quest, her chapters are interspersed by those she is growing up around, each one of those is told in the third person, but for their chapter stays with their perspective and views the others. And the last chapter circles back to the beginning and is given to the mother.

The novel begins with Florens beginning to tell us her story/confession and her telling of it will also be the second to last chapter, where she thinks of her mother and what she wishes her to know. We learn of the plantation where she lived with her mother and younger brother and the accompanied journey she made to her new owner Jacob, given to him in payment for a debt.

It is around 1690, at a time when anyone, of any colour, race or creed could be rented, sold or traded.

The beginning begins with the shoes. When I was a child I was never able to abide being barefoot and always beg for shoes, anybody’s shoes,even on the hottest days. My mother, a minha mãe, is frowning, is angry at what she says are my prettifying ways.

We meet the other women living on Jacob’s farm, how he has “acquired” them, who he is and why he lives the way he does. And the blacksmith, a free man, the turning point of the novel.

To tell any more would be a disservice, for it is a novel to discover, letting it reveal its layers to you.

Their drift away from others produced a selfish privacy and they had lost the refuge and the consolation of a clan. Baptists, Presbyterians, tribe, army, family, some encircling outside thing was needed. Pride, she thought. Pride alone made them think that they needed only themselves, could shape life that way, like Adam and Eve, like gods from nowhere beholden to nothing except their own creations. She should have warned them, but her devotion cautioned against impertinence. As long as Sir was alive it was easy to veil the truth: that they were not a family-not even a like-minded group. They were orphans, each and all.

The Spiralling Narrative

Without looking at the structure, and trying to understand the author’s intention by it, I can see why one might struggle with this, I went back and reread the first chapter countless times as I read forward, because it reveals so much that is understood as we progress. I benefited so much from each time I circled back and reread that beginning. And felt the excitement of realising what Morrison was doing. A lyrical revelation.

The man Jacob gets one chapter, but the first person narrator is the little girl Florens who we see at eight years and at sixteen years and we only understand why, when we read the very last voice, that of her mother, and whose intention it was, who spotted that opportunity, A Mercy. The story is seen from these different angles, perspectives, narrative voices circling the oblivious character.

Just wow.

Photo by Johannes Plenio on Pexels.com

A simple telling of a complex novel in the hands of one of the greats.

To use my own symbolism, which at the end I draw in the back of the book, to capture it immediately it comes to mind, it’s like learning about how trees live in communities and support each other.

There is what you see above ground, what lies below that connects them, and then there is the environment in which they grow, are nurtured, or might wither. And the small mercies.

It was not a miracle. Bestowed by God. It was a mercy. Offered by a human.

Further Reading

Short Video (3 mins) Toni Morrison on her character Florens in ‘A Mercy’

Henry is making his living as a blacksmith, after the disappointment of arriving in New York and struggling to find work due to discrimination by employers against the Irish –

Henry is making his living as a blacksmith, after the disappointment of arriving in New York and struggling to find work due to discrimination by employers against the Irish –  Tammye Huf is an American author now living in the UK. Her debut novel A More Perfect Union was inspired by the true story of her great-great grandparents, an exploration of identity, sacrifice, belonging, race and love. It was featured on the Jo Whiley Radio 2 Book Club.

Tammye Huf is an American author now living in the UK. Her debut novel A More Perfect Union was inspired by the true story of her great-great grandparents, an exploration of identity, sacrifice, belonging, race and love. It was featured on the Jo Whiley Radio 2 Book Club. The witch trials of Salem began in March 1692 with the arrests of Sarah Good, Sarah Osborne and the black slave, Tituba, based on forced confessions. The trials were started after people had been accused of witchcraft, primarily by teenage girls, though traced to adult concerns and adult grievances. Quarrels and disputes with neighbors often incited witchcraft allegations.

The witch trials of Salem began in March 1692 with the arrests of Sarah Good, Sarah Osborne and the black slave, Tituba, based on forced confessions. The trials were started after people had been accused of witchcraft, primarily by teenage girls, though traced to adult concerns and adult grievances. Quarrels and disputes with neighbors often incited witchcraft allegations. I had read nothing about the witch trials before, though I’d heard of them, but I’m glad that this was my introduction, to see this little segment of American history, through the eyes of the innocent black slave, Tituba and her husband John.

I had read nothing about the witch trials before, though I’d heard of them, but I’m glad that this was my introduction, to see this little segment of American history, through the eyes of the innocent black slave, Tituba and her husband John.

I was completely drawn into the dual narrative story and loved both parts of it, modern day Scotland and mid 1800’s Russia and the Caucasus.

I was completely drawn into the dual narrative story and loved both parts of it, modern day Scotland and mid 1800’s Russia and the Caucasus.

Hester is the ferryman’s daughter, it is Autumn 1908 and she lives in a Cornish seaside village with her family, whose lives are soon to be forever changed when her mother dies.

Hester is the ferryman’s daughter, it is Autumn 1908 and she lives in a Cornish seaside village with her family, whose lives are soon to be forever changed when her mother dies.

A New York Times Bestseller, Pachinko is a work of historical fiction set in Korea and Japan that follows the lives of one family and how their circumstances and choices continue to reverberate through the generations.

A New York Times Bestseller, Pachinko is a work of historical fiction set in Korea and Japan that follows the lives of one family and how their circumstances and choices continue to reverberate through the generations.

It is not until page 142 that we come across ‘pachinko’, the Japanese name for pinball, a huge industry in Japan at the entry into the workforce of Sunja’s son Mozasu.

It is not until page 142 that we come across ‘pachinko’, the Japanese name for pinball, a huge industry in Japan at the entry into the workforce of Sunja’s son Mozasu. I absolutely loved this book, it was such an immersive experience, I could feel myself slowing it right down not wanting it to end.

I absolutely loved this book, it was such an immersive experience, I could feel myself slowing it right down not wanting it to end. When Sam comes home and finds his wife in tears, we learn it is September 1937 and Bessie Smith (43), Empress of the Blues, has sung her last lament.

When Sam comes home and finds his wife in tears, we learn it is September 1937 and Bessie Smith (43), Empress of the Blues, has sung her last lament. Eugène Jacques Bullard left America for France at a young age, inspired by the words of his father (from Martinique, enslaved in Haiti, he took refuge with and married a Native American of the Creek tribe) who said to his son « un homme y était jugé par son mérite et non pas par la couleur de sa peau » that a man was judged there by his merit and not by the colour of his skin.

Eugène Jacques Bullard left America for France at a young age, inspired by the words of his father (from Martinique, enslaved in Haiti, he took refuge with and married a Native American of the Creek tribe) who said to his son « un homme y était jugé par son mérite et non pas par la couleur de sa peau » that a man was judged there by his merit and not by the colour of his skin. Bernice L. McFadden’s ancestors are named at the back of the book as are some of the musicians, dancers and singers who make an appearance. By the end, I just wanted Harlan to be safe and it was with some relief that I read the closing chapters and wondered if that was the true version of events or the life-saving imagination of Ms McFadden.

Bernice L. McFadden’s ancestors are named at the back of the book as are some of the musicians, dancers and singers who make an appearance. By the end, I just wanted Harlan to be safe and it was with some relief that I read the closing chapters and wondered if that was the true version of events or the life-saving imagination of Ms McFadden. What a perfect way to navigate through 500 years of history of a country, without ever getting bogged down in the detail, to follow the lives of daughters, a matrilineal lineage, whose patterns are affected if not dictated by the context of the era within which they’ve lived.

What a perfect way to navigate through 500 years of history of a country, without ever getting bogged down in the detail, to follow the lives of daughters, a matrilineal lineage, whose patterns are affected if not dictated by the context of the era within which they’ve lived. I absolutely loved it, I read this because I seek out works by women in translation to read in August for #WITMonth and finding a book like this is such a joy, for it gives so much in its reading, great storytelling, a potted history of Brazil, a unique multiple women’s perspective and an introduction to an award winning author, the writer of ten novels, this her first translated into English.

I absolutely loved it, I read this because I seek out works by women in translation to read in August for #WITMonth and finding a book like this is such a joy, for it gives so much in its reading, great storytelling, a potted history of Brazil, a unique multiple women’s perspective and an introduction to an award winning author, the writer of ten novels, this her first translated into English. Much of the research she encountered were accounts of perspectives that didn’t at all fit with what she sought to show, planters accounts “of negroes child-like ways” and their wives equally misconceived notions on their “defects of character”.

Much of the research she encountered were accounts of perspectives that didn’t at all fit with what she sought to show, planters accounts “of negroes child-like ways” and their wives equally misconceived notions on their “defects of character”.

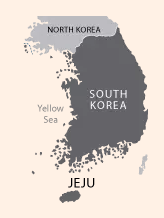

A fascinating read, an insight into a unique way of life by women known as ‘haenyeo‘ on the coastal, volcanic island of Jeju, in South Korea and a well-researched, thought-provoking work of historical fiction.

A fascinating read, an insight into a unique way of life by women known as ‘haenyeo‘ on the coastal, volcanic island of Jeju, in South Korea and a well-researched, thought-provoking work of historical fiction.

Though the islanders live a simple life, they suffer the consequence of being a resting place for occupying forces, initially when the story opens, it is the Japanese military who occupy the island and create a bad feeling.

Though the islanders live a simple life, they suffer the consequence of being a resting place for occupying forces, initially when the story opens, it is the Japanese military who occupy the island and create a bad feeling. This mid-section of the novel is subsumed by the changing political situation and the dire effect on the local population, nearly all of whom lose members of their family. Young-Sook’s family suffer severe tragedy, creating a deep resentment, causing her to abandon her friendship with Mi-ja.

This mid-section of the novel is subsumed by the changing political situation and the dire effect on the local population, nearly all of whom lose members of their family. Young-Sook’s family suffer severe tragedy, creating a deep resentment, causing her to abandon her friendship with Mi-ja.