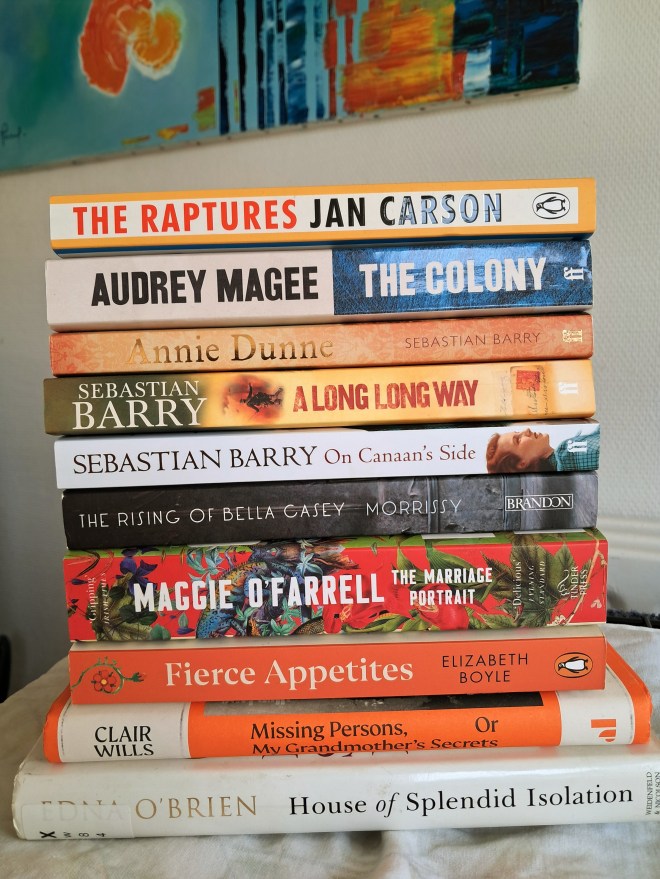

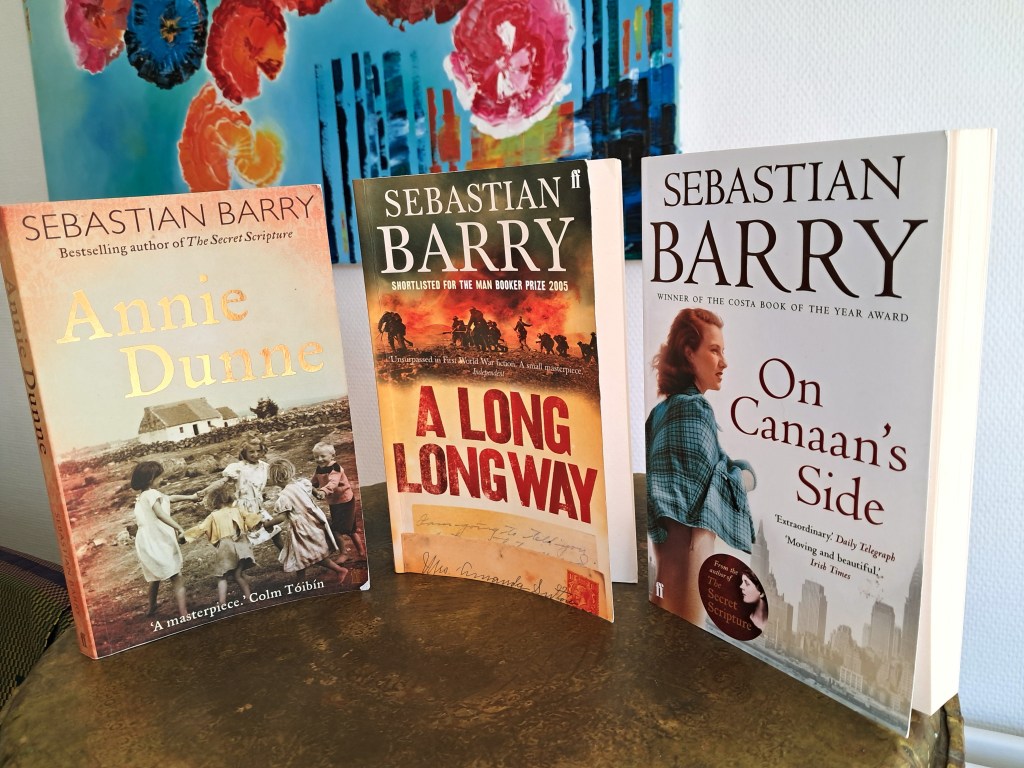

Continuing with the Dunne Family trilogy, after the play and the first novel Annie Dunne, comes a World War I novel, one that was shortlisted for the Booker Prize in 2005.

It is about the short life of Annie’s brother William Dunne, the harsh realities of the Great War and the conflicting loyalties of Irish men at war fighting for the British Army, while others at home were fighting for freedom, putting these men at a crossroads in history, during this revolutionary shift towards Irish independence.

Dunne Family #3 Willie Dunne

Willie Dunne was born in the withering days of 1896, named after an Uncle and the long-dead Orange King, because his father took an interest in such matters.

The only son in a family of four children, he couldn’t be held responsible for not meeting the first expectation his six foot six father held of him, to join the police force like himself.

For his growing slowed to a snail’s pace, and his father stopped putting him against the wallpaper, such was both their grief, for it was as clear as day that Willie Dunne would never reach six feet, the regulation height for a recruit.

Rather, he would join that group of young men:

piled up in history in great ruined heaps, with a loud and broken music, human stories told for nothing, for ashes, for death’s amusement, flung on the mighty scrapheap of souls, all those million boys in all their humours to be milled by the mill-stones of a coming war.

Conflicting Loyalties, In Love and War

Losing their mother when Willie was twelve, after the birth of the youngest daughter Dolly, they would move with their father into Dublin Castle in 1912.

During the unrest after a lock out his father, now high up in the Dublin Metropolitan Police lead a charge against the crowd that brutalised some citizens, including a man named Lawlor he wished to make amends to. Which is how Willie met the man’s daughter, Gretta, a secret he kept from his father, a desire he would carry with him throughout the coming war.

The Promise of Home Rule, Just Send Us Your Boys

Though the Ulstermen joined the same army, it was for an opposite reason, to prevent home rule, so Willie’s father said, wholely approving. A Catholic and a Mason, it was for King and country and Empire he said a man should go and fight for, never expecting that his son would depart as soon as he did.

The Parliament in London had said there would be Home Rule for Ireland at the end of the war, therefore, said John Redmond, Ireland was for the first time in seven hundred years in effect a country. So she could go to war as a nation at last – nearly – in the sure and solemnly given promise of self-rule. The British would keep their promise and Ireland must shed her blood generously.

Willie joins the Royal Dublin Fusiliers in 1914 and is soon in the trenches in Belgium, thinking of home and Gretta, disappointed that she doesn’t reply to any of his letters, but remembering that she had not been able to give her word that she would marry him. He would write to her as if she had.

Dirt, Death and Ditties

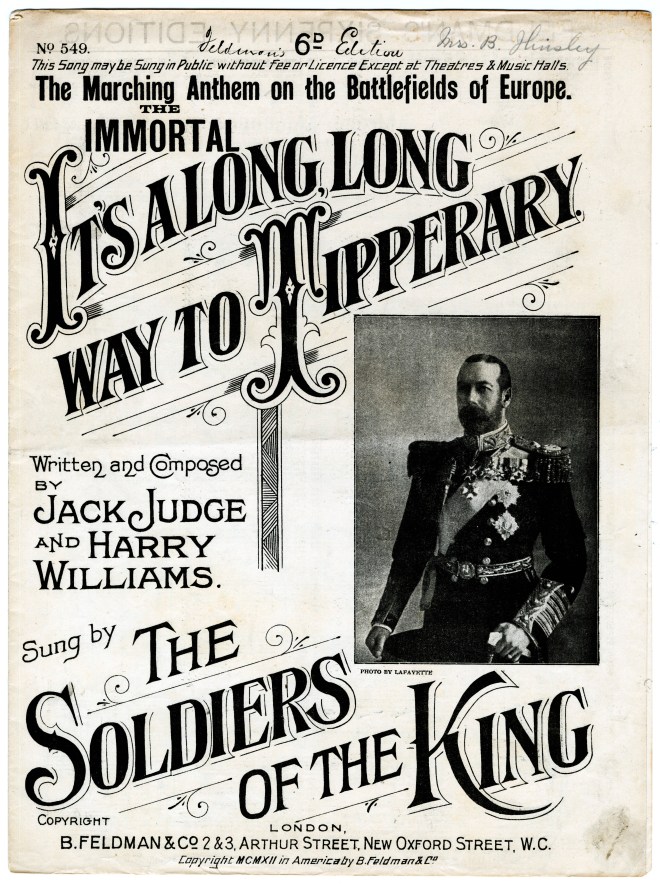

Days at war were tough, dirty and relentless. As they marched between locations, the men would sing songs, most of which not everyone knew, but there was one that had everyone singing and learning, making them all feel a little better as they bawled out the lyrics.

Every man Jack of them knew ‘Tipperary’ and sang it as if most of them weren’t city-boys but hailed from the verdant fields of that country. Probably every man in the army knew it, whether he was from Aberdeen or Lahore.

But 1915-1916 was a complicated time to be fighting for King and country in Ireland. That used to indicate the same allegiances, but no longer, and for those young boys at the front, facing assault after assault, the thought of being perceived as an enemy by some back home became too confusing for them to handle.

An Uprising Confuses Irish Soliders

On his first leave in April 1916, all is well and Gretta seems to have softened towards him being away but as they are returning to the boat, they get called off and marched back towards the city to Mount Street, where they are confused by the sound of shots being fired. When a citizen offers a printed sheet to him to read, it provokes a violent reaction.

‘Step back in, Private,’ called the Captain. ‘Don’t parley with the enemy.’

‘What enemy?’ said Willie Dunne. ‘What enemy, sir?’

‘Keep back away or I will shoot him.’

When the Captain puts his gun against the citizen’s temple, Willie steps back, but none of them are given any explanation as to what the conflict was about. They are ordered to fight and in an interaction with a man who gets shot, Willie learns who the enemy are, his own countrymen, Irishmen fighting for Ireland, for freedom.

No Empathy in Judgement

When they return to the front in Flanders, thoughts and images of that Easter day won’t leave him.

Nothing had changed just here where he found himself – utter change was just across the plains. Nothing had changed. But something had changed in Willie Dunne.

Unable to reconcile what he had witnessed, Willie writes to his father of his feelings, not realising the storm erupting at home and the hardened position his father has taken, after the armed Easter Rebellion, a violent revolt against British rule. The soliders are kept deliberately vague about what is going on, for Willie saw only one of his fellow countrymen, not an enemy.

Despondency Destroys

They continue to fight on losing more and more of their compatriots and wondering what it is all for given what is happening back home in Ireland, where rows rage over conscription, Ireland no longer is willing to send their sons. Yet those who are there fight on, for each other, and for the memories of the many they have already lost.

Mothers in Ireland said they would stand in front of their sons and be shot before they would let them go…the Nationalists wouldn’t stand for it. Said King George could find lambs for the slaughter in his own green fields from now on.

From the loss of his mother, to his height and the brutality of war, Willie’s young life is beset with hardship, made all the worse by his father’s lack of understanding and other betrayals he will encounter. He finds solace and loyalty in his comrades, when his family and others disappoints him.

It’s not an easy read, but it evokes the comradary of Irish soliders during war time, the terror, cruelty and degradation of humanity war brings about.

Fiction and Storytelling Inform Us of History

Although it is not a history of Irish independence or the events that lead to it, it prompted me to read up about the Easter Rising and better understand the compromising situation those young Irish men fighting in the Great War would have been in.

It is a subject, the author said in an interview, that was not taught in schools, the focus being on the Easter Rising, than the tens of thousands of men fighting in Flanders.

In Remembrance

Reading about Willie’s experience in the Great War made me think of who in our own families was affected by World War 1. As I mentioned in my summary planning post Reading Ireland Month 2025, I discovered that my ancestor Edmund Costley, like Willie Dunne was born in 1896, and one of that decimated generation of youth born around then, who perished by the thousands.

Edmund was in the Irish Guards Second Battalion, the same regiment as John Kipling, son of Rudyard Kipling. John was killed within three months of going to the front and his father in 1917, committed to write a chronicle of what the Irish Guards did during the war. That book, The Irish Guards In The Great War: The Second Battalion: Edited and Compiled from Their Diaries and Papers is an incredible of information in which to understand how it was for these young men.

Further Reading

Article: The Easter Rising 1916: the catalyst to becoming a Republic by Sinead Murphy, My Real Ireland

An Interview with Sebastian Barry About A Long Long Way by Mark Harkin

50 Facts About Ireland’s 1916 Easter Rising by Matt Keough, Irish Central

My review of: Old God’s Time (2023) by Sebastian Barry

Author, Sebastian Barry

The 2018-21 Laureate for Irish Fiction, Barry had two consecutive novels shortlisted for the Booker Prize, A Long Long Way (2005) and the top ten bestseller The Secret Scripture (2008), before Old God’s Time was longlisted for the Booker Prize in 2023. He has also won the Kerry Group Irish Fiction Prize, the Irish Book Awards Novel of the Year and the James Tait Black Memorial Prize.

His novels have twice won the Costa Book of the Year award, the Independent Booksellers Award and the Walter Scott Prize. Barry was born in Dublin in 1955, and now lives in County Wicklow.