Clear by Carys Davies (Granta) is one of those books that stood out for me from the moment I first saw it mentioned. I could tell it was going to be excellent. And it is.

That atmospheric painting, Moonlight on the Norwegian Coast by artist Baade Knud Kunstenr (1876), depicting a fisherman looking out to sea, reading the dark and broody skies, where through a gap, there beholds light, promise.

What will he decide?

1843 Scotland, the Great Disruption, the Clearances

Clear is an exceptional novella, set in 1843 Scotland. It is about a quiet, worrisome, rebel pastor, John Ferguson and his wife Mary, who met rather unexpectedly and dramatically during one of the Comrie earthquakes; and Ivar, the lone islander out there in the North Sea, somewhere between the Shetland Islands and the coast of Norway.

We encounter them in the months after The Great Disruption, when 474 clergy radically separated from the Church of Scotland over government interference in appointments and ‘patronage‘, the dominant influence of wealthy landowners in putting those they wished in position and removing others unwanted.

She remembered a dinner, a long time ago now, at her father’s house in Penicuik, where the talk had turned to a removal somewhere north of Cannich, and remembered her father remarking that he was surprised there was still anyone left to remove – that he thought all the big estates must by now have been thoroughly cleansed of their unwanted people.

Desperate Times, Desperate Measures

John, like other rebel ministers who signed the controversial Act of Separation and Deed of Demission, is now under financial pressure to meet all his new responsibilities, thus he accepts a paid role from a landowner’s factor, much to the consternation of his wife, to visit a remote island in the north to evict the last inhabitant, part of the final throes of the Highland Clearances.

The important thing was not to become dispirited – the important thing was to remember that this was a job, an errand: a means to a very important end.

He sets out by boat, and is left on the island, with the promise of a return berth (with his charge in tow) some weeks ahead. Things don’t go quite to plan and all that passes sets up the already complex dilemma this man faces.

Life on Scottish Islands

Set in that mid 1800’s period on the island, felt so authentic, it reminded me of reading a Kathleen Jamie essay from Findings.

The author brings alive the damp, blustery, natural environment, the daily rhythms of Ivar and his few animals, his survival skills.

Then the precise observations of his encounter and time spent with the first man he has seen in years and the portrayal of the care he expends – just brilliant.

He’d been out very little this past spring, first because of his illness and then because of the bad weather when it had been too rough for much outdoor work, and impossible to fish off the rocks – the sea restless and unruly and wild, spindrift from the heavy breakers striking against the shore and forming a deep mist along the coast. He’d spent most of his time knitting, mainly sitting in his great chair next to the hearth but also sometimes on the stool in the byre with Pegi, occasionally talking to her but mostly just sitting in her company with a sock or cap or whatever else he was making.

As well as the natural environment, there is the language Ivar speaks, neither Scots nor English, something else altogther.

Ivar was not garrulous. He did not speak often, and when he did his sentences were short.

Woven through them were a few words John Ferguson thought he recognised – a handful that sounded like ‘fish’, ‘peat’, ‘sheep’, ‘look’, ‘me’, ‘I’, but delivered in an accent that made it impossible to be sure.

Scottish Genealogy and Family History

What made this short novel all the more interesting for me was that I have been researching my Scottish ancestors from the late 1700’s to late 1800’s in and around Dundee, people involved in the weaving and shipping industries.

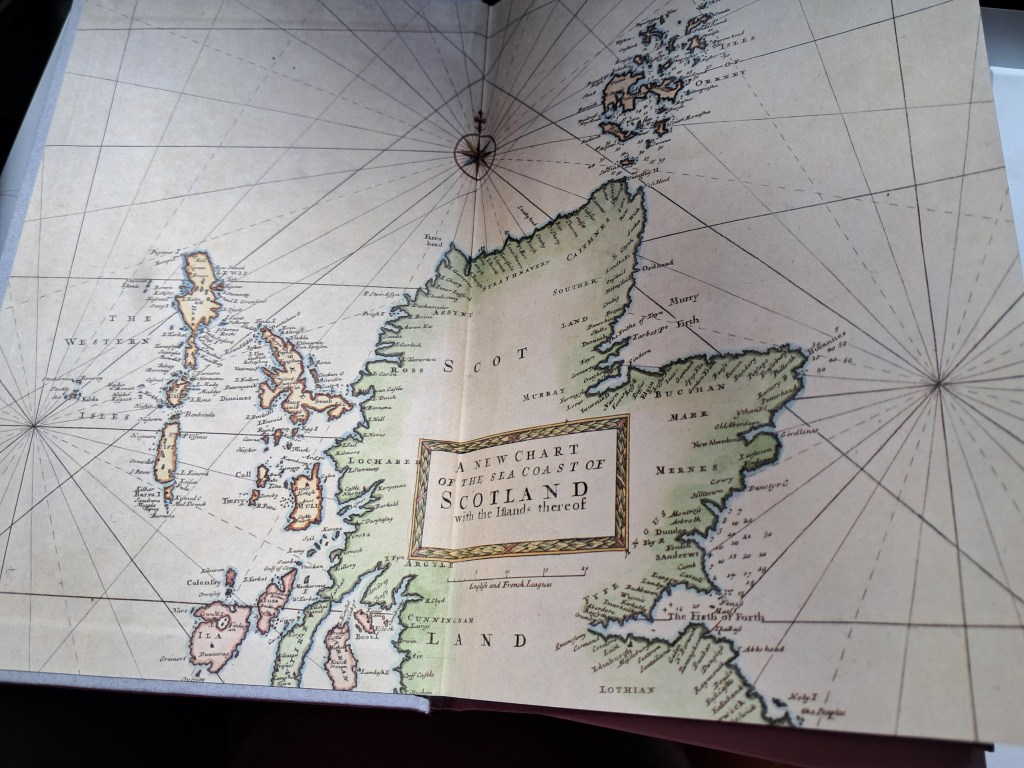

Reading a novel set in this same period felt strangely but appropriately familiar; the detail on the map on the inside cover, shown here, add to that sense of time and wonder.

If you have spent any time poring over Scotland’s National Records, census indexes and records of the historic environment (archaeological sites, buildings, industry and maritime heritage), then this book is like a short, entertaining breather from that, to embark on another journey, while staying immersed in the era. Reading newspapers or stories, looking at artworks and photos really awakens the lives of those who have gone before us.

Artists Using Photography

When the Great Disruption occurred, the meeting of the First Assembly to sign the Deed was recorded via a painting depicting all 474 men. It was a culturally significant moment. The painting, by the artist David Octavius Hill was internationally important as the first work of art painted with the help of photographic images. Robert Adamson, photographer, had a Calotype studio (an early photographic process introduced in 1841) in Edinburgh and he worked in partnership with Hill, realising the potential of the new medium.

In the novel Clear, one of the significant items that John Ferguson takes with him to the island, is a framed portrait of his wife Mary, an object that is a catalyst of many different emotions in the two men on the island.

The picture of Mary Ferguson in the tooled-leather frame was a colotype by Robert Adamson.

It was made in Edinburgh a few months after the Fergusons’ marriage, and six weeks after the Revernd John Ferguson resigned his living in the city’s northern parish of Broughton and became a poor man by throwing in his lot with the Free Church of Scotland.

Certain aspects of Scottish historical importance are subtly planted like this throughout the text and while they do not distract from it (unless like me you go hunting for those references), they are a welcome authentic addition to an already scintillating text.

I absolutely loved it, my copy now has many scribbled pencil jottings all over it and this is one I would definitely read again as I feel as though there is more to unravel if I went beachcombing through it!

Highly Recommended.

I also read this during March to coincide with Karen at Booker Talk’s Reading Wales Month 2025.

Further Reading

New York Times review: In ‘Clear,’ a Planned Eviction Leads to Two Men’s Life-Changing Connection

Guardian review: Clear by Carys Davies review – in search of a shared language

Author, Carys Davies

Carys Davies‘s first novel West won the Wales Book of the Year Fiction Award, was Runner-Up for the Society of Author’s McKitterick Prize and shortlisted for the Rathbones Folio Prize. Clear has been longlisted for the Walter Scott Historical Fiction Prize 2025.

Her short stories have been widely published and broadcast on BBC Radio 4. Her second collection, The Redemption of Galen Pike, won the Frank O’Connor International Short Story Award 2015. She lives in Edinburgh.

Laddy Merridew comes to spend time with his Gran in an old Welsh mining town in Vanessa Gebbie’s ‘A Coward’s Tale’. Not happy with his lot, lost in the in-between, here where he doesn’t feel like he belongs so starts skipping school and there, the home he has come from that is breaking apart and will never be as it was and what’s worse, is requiring him to make decisions he feels incapable of making.

Laddy Merridew comes to spend time with his Gran in an old Welsh mining town in Vanessa Gebbie’s ‘A Coward’s Tale’. Not happy with his lot, lost in the in-between, here where he doesn’t feel like he belongs so starts skipping school and there, the home he has come from that is breaking apart and will never be as it was and what’s worse, is requiring him to make decisions he feels incapable of making. Once I got into the tales and understood the framework, I enjoyed the book, but I admit it took three attempts before the stories managed to carry me away with their rhythmic, poetic prose. However they are splendid tales and told with a unique captivating voice that puts the reader right in that square with all the other listeners, empathizing with each of the characters that the adored Ianto Jenkins brings to life for them.

Once I got into the tales and understood the framework, I enjoyed the book, but I admit it took three attempts before the stories managed to carry me away with their rhythmic, poetic prose. However they are splendid tales and told with a unique captivating voice that puts the reader right in that square with all the other listeners, empathizing with each of the characters that the adored Ianto Jenkins brings to life for them. Au mois de mai, fais ce qu’il te plait.

Au mois de mai, fais ce qu’il te plait. as a symbol of porte-bonheur or good luck.

as a symbol of porte-bonheur or good luck.