My Fight To Bring A New African Voice To The Climate Crisis

Vanessa Nakate is a young Ugandan woman who became concerned about the effect of climatic conditions and change on her country and in particular the knock on effect floods, crop destruction would have on women and girls, disproportionately affected, as explained in her book.

Alternative Learning Experiences for Children

She decided to organise a strike, just herself, her two younger brothers (14 & 10), two visiting cousins (11 &9) and another cousin her age. It would be the six of them, holding up a few placards they made, and they would stand in four busy locations in Kampala, moving from each place after 30 minutes when her alarm went off.

“What shall we write?” Varak, the nine-year-old asked.

I wanted us to express something positive, and to ensure that my younger family members held placards they themselves would understand. We decided to pick slogans we thought wouldn’t be too threatening, and so wrote several, in English.

Trees Are Important For Us

Nature Is Life

When You Plant A Tree, You Plant A Forest

Thanks For The Global Warming (that was our sarcastic one) and

Climate Strike Now

We also drew some trees next to the letters.

Nothing dramatic happened, no one told to stop, but it was the beginning of an interest, of a young woman finding her cause and taking an action, that would lead her to learning and discovering more, to connecting with others, to finding local solutions and developing a presence and a new voice, on an international stage.

One woman stopped and told them of some trees being cut down to make way for a school, that they should be stopped. Each time Nakate went out and had the opportunity to engage or had a response on social media, it would often lead her to the next idea, it would put her in touch with others who genuinely wanted something to be done, their voices to be heard.

How One Exclusion Can Lead to Greater Inclusion

It is an excellent read, because it follows her personal journey, as a young person with little knowledge about activism and from this small spark of quiet daring (despite her anxieties, insecurities and fear of judgement), she shares her perseverance, her growing knowledge, the first invitations to attend international conferences and events, to a tipping point, when many more (including me) would hear about her – after she was cropped out of a photograph of young climate change activists including Greta Thunberg at Davos, Switzerland during the WEF (World Economic Forum) in January 2020.

My message was, and is, straightforward: People in Uganda, in Africa, and across what’s called the Global South, are losing their homes, their harvests, their incomes, even their lives, and any hopes of a livable future right now.

The Quiet Methodical, Cooperative Approach

What makes her message and her actions all the more interesting is that she takes a quiet methodical approach to doing things in her own authentic way, in a country where she is aware of both dangers and expectations, so does nothing foolhardy, acting responsibly.

However, when there is the opportunity for advancement of her cause and for manageable solutions she can implement herself, she steps up to those and has helped make life more amenable for many families already, while continuing to pursue the wider message, especially to young people, future leaders, for whom it will be better if they encounter this knowledge through their early education, than as adults already fixed in their opinions or influenced by position or power.

Since I’m always looking for solutions that reflect reality and the need to get the message out, I decided that instead of suggesting that students walk out of classes, I’d try to take the climate strikes into schools – where they could form part of the curriculum in a way that I’d wished climate change had been when I was a young girl.

The first school she approached in this way was open to this collaboration, the teachers assembled 100 students inside the compound, Vanessa Nakate gave a short speech explaining what the strike was about, in a way that could relate to and then lead them in a chant, the teachers encouraging the children to chant even louder.

What do we want? Climate justice. When do we want it? Now.

Genuine Efforts and Action Do Get Noticed

In 2019 she received an email from the UN Secretary General’s office in New York, an invitation to attend the Youth Climate Summit. Understandably, she and her parents didn’t think it was real, but it was, she would be the first person in her family to travel outside of Uganda and that would signify a new beginning in her self-appointed role.

The first half of the book is about the development of her role, the logistics of trying to attend events and to becoming involved in meaningful solutions at home, such as the Vash Green Schools Project (supports the installation of solar panels and building clean cooking stoves in primary schools) and to realising the need for self-care due to overwhelm.

Role Models and Inspiration, Making Connections

The second half gives a bigger picture of the wider issues, sharing information from others she interviewed and has been inspired by, including the late Wangari Maathai, the inspiring Kenyan woman who created the Green Belt Movement and made much progress (often hindered by men in power) who was the first African woman to win the Nobel Peace Prize in 2004 for ‘her contribution to sustainable development, democracy and peace’. Read my review of her autobiography Unbowed here.

Coincidentally COP28 is happening right now in Dubai and Vanessa Natake is there with others trying to get their message across to world leaders who have the power to phase out fossil fuels and support equitable and safe renewable energies. Her article appearing in today’s Guardian below.

I really enjoyed reading this book and learning more about how Vanessa Natake became a voice for her country and continent and inspired so many youth and adults to both learn and do more to try and halt the destruction that is affecting them all.

Highly Recommended.

Further Reading

The Guardian Opinion: At Cop28 it feels as if humanity’s shared lifeboat is sinking by Vanessa Nakate

Author & Activist, Vanessa Nakate

Vanessa Nakate is a Ugandan climate justice activist. She grew up in Kampala and started her activism in December 2018 after becoming concerned about the unusually high temperatures in her country. Inspired by Greta Thunberg to start her own climate movement in Uganda, Vanessa Nakate began a solitary strike against inaction on the climate crisis in January 2019. She founded the Youth for Future Africa and the Africa-based Rise Up Movement and spearheaded the Save Congo Rainforest campaign.

She has addressed world leaders at multiple climate summits and appeared on the cover of TIME magazine in 2021 (featuring on the Time100 Next list in 2021). She was appointed a UNICEF Goodwill Ambassador in 2022.

Nakate and her work have been featured in the New York Times, the Guardian,Yes!,Vox, Vogue, the Huffington Post, the International Women’s Forum, and the Global Landscapes Forum, and on globalcitizen.org, greenpeace.org, CNN, the BBC, PBS, and United Nations media. She lives in Kampala, Uganda.

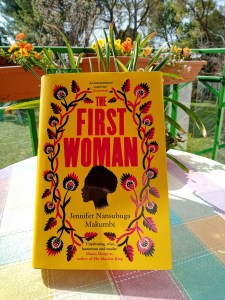

The First Woman might even have surpassed her debut novel Kintu which was fabulous and my outstanding read of 2018.

The First Woman might even have surpassed her debut novel Kintu which was fabulous and my outstanding read of 2018. The story is divided into five sections; The Witch (Nattetta, Bugerere, Uganda 1975), The Bitch (Kampala 1977), Utopia, When The Villages Were Young (Nattetta 1934) and Why Penned Hens Peck Each Other (1983).

The story is divided into five sections; The Witch (Nattetta, Bugerere, Uganda 1975), The Bitch (Kampala 1977), Utopia, When The Villages Were Young (Nattetta 1934) and Why Penned Hens Peck Each Other (1983). A Ugandan fiction writer, her first novel, Kintu, won the Kwani? Manuscript Project in 2013. Her second book is a collection of short stories, titled Manchester Happened (2019) for the UK/Commonwealth publication and Let’s Tell This Story Properly (US/Canada). It was shortlisted for The Big Book prize: Harper’s Bazaar.

A Ugandan fiction writer, her first novel, Kintu, won the Kwani? Manuscript Project in 2013. Her second book is a collection of short stories, titled Manchester Happened (2019) for the UK/Commonwealth publication and Let’s Tell This Story Properly (US/Canada). It was shortlisted for The Big Book prize: Harper’s Bazaar. This is what appealed to me immediately about the prospect of reading Jennifer Nansubuga Makumbi’s Kintu. It promises to do the same thing, to take the reader from where we are at today in a culture and link it back to the past, from modern day Uganda to the era of when the region was ruled as a kingdom. And it succeeds brilliantly, in a way rarely seen in literature in the UK/US published today.

This is what appealed to me immediately about the prospect of reading Jennifer Nansubuga Makumbi’s Kintu. It promises to do the same thing, to take the reader from where we are at today in a culture and link it back to the past, from modern day Uganda to the era of when the region was ruled as a kingdom. And it succeeds brilliantly, in a way rarely seen in literature in the UK/US published today.

Some are haunted by ghosts of the past, thinking themselves not of sound mind, particularly when aspects of their childhood have been hidden from them, some have prophetic dreams, some have had a foreign university education and try to sever their connections to the old ways, though continue to be haunted by omens and symbols, making it difficult to ignore what they feel within themselves, that their mind wishes to reject. Some turn to God and the Awakened, looking for salvation in newly acquired religions.

Some are haunted by ghosts of the past, thinking themselves not of sound mind, particularly when aspects of their childhood have been hidden from them, some have prophetic dreams, some have had a foreign university education and try to sever their connections to the old ways, though continue to be haunted by omens and symbols, making it difficult to ignore what they feel within themselves, that their mind wishes to reject. Some turn to God and the Awakened, looking for salvation in newly acquired religions.