On 11 March the longlist for the International Booker Prize 2024 was announced. It was a notable celebration for Latin American fiction, with authors representing Brazil, Argentina, Peru and Venezuela on the list.

The 13 novels cover 10 different languages, Spanish, Italian, Swedish, German, Albanian, Portuguese, Dutch, Korean, Polish and Russian. They span multiple genres and generations, as well as personal and national histories, oppressive regimes and the shadow of colonialism. Though they may seem unfamiliar, many have been bestsellers in their home countries.

Take the Quiz!

If you are not sure which of these books might be your style, you can do what I did, and take their quiz!

-> Quiz: which book from the International Booker Prize 2024 longlist should you read?

I’ll let you know which book they have recommended I read at the end of this post. If you take the quiz, let me know in the comments below which book came up for you.

The 13 Novels on the Longlist

The 13 books chosen by this year’s judges represent the best in translated fiction, published in the English language in the UK and Ireland selected from 149 books published between 1 May 2023 and 30 April 2024.

I have two on my shelf already, but not the one the quiz recommended I should read!

The titles are listed below with a description and the judges’ comment:

Not a River by Selva Almada (Argentina), tr. Annie McDermott (Spanish) (#1 on my shelf)

– Selva Almada’s novel is the finest expression yet of her compelling style and singular vision of rural Argentina.

Three men go out fishing, returning to a favourite spot on the river despite their memories of a terrible accident there years earlier. As a long, sultry day passes, they drink and cook and talk and dance, and try to overcome the ghosts of their past. But they are outsiders, and this intimate, peculiar moment also puts them at odds with the inhabitants of this watery universe, both human and otherwise. The forest presses close, and violence seems inevitable, but can another tragedy be avoided?

‘Not A River moves like water, in currents of dream and overlaps of time which shape the stories and memories of its protagonists. Enero and El Negro have brought their young friend and protégé Tilo on a fishing trip along the Paraná River in Argentina. The island where they set up camp pulses with its own desires and angers, tensions equal to those of the men who have come together on its shores. Alongside the story of these grief-marred characters, the author offers those of the women of the town – and what luck to root for or mourn them: the mother whose ever-growing fires engulf us, her two flirtatious, youth-glowed daughters, and the almost-mythical manta ray who becomes one of the guardians and ghosts of this throbbing, feverish novel.’

Simpatía by Rodrigo Blanco Calderon (Venezuela), tr. Noel Hernández González & Daniel Hahn (Spanish)

– A suspenseful novel with unexpected twists and turns about the agony of Venezuela and the collapse of Chavismo.

Set in the Venezuela of Nicolas Maduro amid a mass exodus of the intellectual class who have been leaving their pets behind. Ulises Kan, the protagonist and a movie buff, receives a text message from his wife, Paulina, saying she is leaving the country (and him). Ulises is not heartbroken, but liberated by Paulina’s departure. As two other events end up disrupting his life even further, Ulises discovers that he has been entrusted with a mission – to transform Los Argonautas, the great family home, into a shelter for abandoned dogs. If he manages to do it in time, he will inherit the luxurious apartment that he had shared with Paulina.

‘In this realistic allegory set in Caracas during Nicolás Maduro’s dictatorship, we meet Ulises, a former orphan who is desperate for a sense of purpose and belonging. His wife has just announced by text message that she is leaving him and his father-in-law has willed him Los Argonautas, a house of accumulating secrets and mythologies. Much like that of Jason of the Argonauts, Ulises’ inheritance is contingent on the completion of a task: to transform the house into a veterinary clinic and kennel for the stray dogs left behind by the elites who have fled the city. Within the madness and austerity of political corruption and historical revisioning, Ulises devotes himself to one of the saner choices left to him: complete the task by saving the dogs, with the help of his Medea-like lover, Nadine, and the leftover animal rescue and house staff. In doing so he simultaneously creates a chosen family and a practice of care that is a stronger balm for the heart than sympathy.’

Kairos by Jenny Erpenbeck (Germany), tr. Michael Hofmann

– An intimate and devastating story of the path of two lovers through the ruins of a relationship, set against the backdrop of a seismic period in European history.

Berlin. 11 July 1986. They meet by chance on a bus. She is a young student, he is older and married. Theirs is an intense and sudden attraction, fuelled by a shared passion for music and art, and heightened by the secrecy they must maintain. But when she strays for a single night he cannot forgive her and a dangerous crack forms between them, opening up a space for cruelty, punishment and the exertion of power. And the world around them is changing too: as the GDR begins to crumble, so too do all the old certainties and the old loyalties, ushering in a new era whose great gains also involve profound loss.

‘An expertly braided novel about the entanglement of personal and national transformations, set amid the tumult of 1980s Berlin. Kairos unfolds around a chaotic affair between Katharina, a 19-year-old woman, and Hans, a 53-year-old writer in East Berlin. Erpenbeck’s narrative prowess lies in her ability to show how momentous personal and historical turning points intersect, presented through exquisite prose that marries depth with clarity. She masterfully refracts generation-defining political developments through the lens of a devastating relationship, thus questioning the nature of destiny and agency. Kairos is a bracing philosophical inquiry into time, choice, and the forces of history.’

What I’d Rather Not Think About by Jente Posthuma (Netherlands), tr. Sarah Timmer Harvey (Dutch)

– A deeply moving exploration of grief, told in brief, precise vignettes and full of gentle melancholy and surprising humour.

What if one half of a pair of twins no longer wants to live? What if the other can’t live without them? This question lies at the heart of Jente Posthuma’s deceptively simple What I’d Rather Not Think About. The narrator is a twin whose brother has recently taken his own life. She looks back on their childhood, and tells of their adult lives: how her brother tried to find happiness, but lost himself in various men and the Bhagwan movement, though never completely.

‘A deeply moving exploration of grief and identity through the lives of twins, one of whom dies by suicide. Posthuma delves into the surviving twin’s efforts to understand and come to terms with the loss of her brother, examining the profound complexities of familial bonds. Posthuma navigates delicate themes with sensitivity and formal inventiveness, portraying the nuances of the twins’ relationship and the individual struggles they face. The author skilfully inflects tragedy with unexpected humour and provides a multifaceted look at the search for meaning in the aftermath of suicide. What I’d Rather Not Think About stands out for its empathetic portrayal of love, loss, and resilience.’

Lost on Me by Veronica Raimo (Italy), tr. Leah Janeczko

– Narrated in a voice as wryly ironic as it is warm and affectionate, Lost on Me seductively explores the slippery relationship between deceitfulness and creativity.

Vero has grown up in Rome with her eccentric family: an omnipresent mother who is devoted to her own anxiety, a father ruled by hygienic and architectural obsessions, and a precocious genius brother at the centre of their attention. As she becomes an adult, Vero’s need to strike out on her own leads her into bizarre and comical situations. As she continues to plot escapades and her mother’s relentless tracking methods and guilt-tripping mastery thwart her at every turn, it is no wonder that Vero becomes a writer – and a liar – inventing stories in a bid for her own sanity.

‘A funny, sharp, wonderfully readable novel in which a fresh, playful voice takes us to the heart of an obsessive, unpredictable family. This engaging book tells the story of a young writer finding her special place where the “most fragile, tender, and comical parts” of herself come dazzlingly to life in wild escapades and moments of unexpected reflection.’

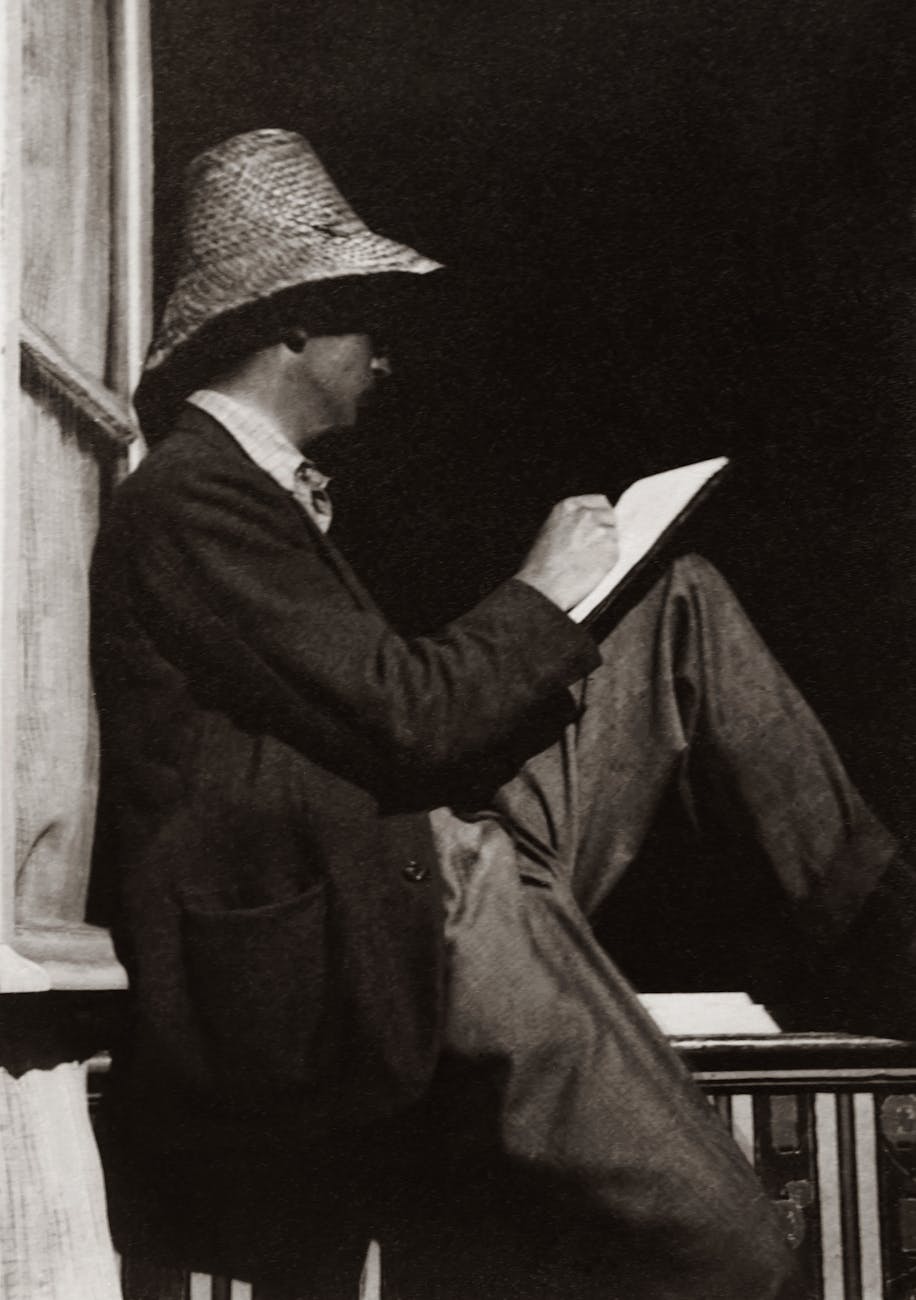

The House on Via Gemito by Domenico Starnone (Italy), tr. Oonagh Stransky (#2 on my shelf)

– Narrated against the vivid backdrop of Naples in the 1960s, The House on Via Gemito has established itself as a masterpiece of contemporary Italian literature.

The modest apartment in Via Gemito smells of paint and white spirit. The living room furniture is pushed up against the wall to create a make-shift studio, and drying canvases must be moved off the beds each night. Federí, the father, a railway clerk, is convinced of possessing great artistic talent. If he didn’t have a family to feed, he’d be a world-famous painter. Ambitious and frustrated, genuinely talented but full of arrogance and resentment, his life is marked by bitter disappointment. His long-suffering wife and their four sons bear the brunt. It’s his first-born who, years later, will sift the lies from the truth to tell the story of a man he spent his whole life trying not to resemble.

‘The House on Via Gemito is a marvellous novel of Naples and its environs during and after the Second World War. The prism for this exploration is the relationship between the narrator and his railway worker / artist father – an impossible man filled with cowardice and boastfulness. His son’s attempt to understand and forgive his father is compelling; we are held through the minutiae of each argument and explosion, each hope and almost-success.’

Crooked Plow by Itamar Vieira Junior (Brazil), tr. Johnny Lorenz (Portuguese)

– A fascinating and gripping story about the lives of subsistence farmers in Brazil’s poorest region.

Deep in Brazil’s neglected Bahia hinterland, two sisters find an ancient knife beneath their grandmother’s bed and, momentarily mystified by its power, decide to taste its metal. The shuddering violence that follows marks their lives and binds them together forever.

‘Bibiana and Belonisía are two sisters whose inheritance arrives in the form of a grandmother’s mysterious knife, which they discover while playing, then unwrap from its rags and taste. The mouth of one sister is cut badly and the tongue of the other is severed, injuries that bind them together like scar tissue, though they bear the traces in different ways. Set in the Bahia region of Brazil, where approximately one third of all enslaved Africans were sent during the height of the slave trade, the novel invites us into the deep-rooted relationships of Afro-Brazilian and Indigenous peoples to their lands and waters – including the ways these communities demand love, gods, song, and dream – despite brutal colonial disruptions. An aching yet tender story of our origins of violence, of how we spend our lives trying to bloom love and care from them, and of the language and silence we need to fuel our tending.’

The Details by Ia Genberg (Sweden), tr. Kira Josefsson

– In exhilarating, provocative prose, Ia Genberg reveals an intimate and powerful celebration of what it means to be human.

A famous broadcaster writes a forgotten love letter; a friend abruptly disappears; a lover leaves something unexpected behind; a traumatised woman is consumed by her own anxiety. In the throes of a high fever, a woman lies bedridden. Suddenly, she is struck with an urge to revisit a particular novel from her past. Inside the book is an inscription: a message from an ex-girlfriend. Pages from her past begin to flip, full of things she cannot forget and people who cannot be forgotten. Johanna, that same ex-girlfriend, now a famous TV host. Niki, the friend who disappeared all those years ago. Alejandro, who appears like a storm in precisely the right moment. And Birgitte, whose elusive qualities shield a painful secret. Who is the real subject of a portrait, the person being painted or the one holding the brush?

‘Ia Genberg writes with a remarkably sharp eye about a series of messy relationships between friends, family and lovers. Using, as she says, “details, rather than information”, she gives us not simply the “residue of life presented in a combination of letters” but an evocation of contemporary Stockholm and a moving portrait of her narrator. She has at times a melancholic eye, but her wit and liveliness constantly break through.’

White Nights by Urszula Honek (Poland), tr. Kate Webster

– A highly artistic study of death encapsulated in moving stories set in Poland’s Beskid Mountains region.

White Nights is a series of thirteen interconnected stories concerning the various tragedies and misfortunes that befall a group of people who all grew up and live(d) in the same village in the Beskid Niski region, in southern Poland. Each story centres itself around a different character and how it is that they manage to cope, survive or merely exist, despite, and often in ignorance of, the poverty, disappointment, tragedy, despair, brutality and general sense of futility that surrounds them.

‘A haunting series of interconnected stories set in a small town in the Beskid Mountains of Poland, a place enveloped by the continuous daylight of the summer months. Through a cast of characters each facing their own existential crises, Honek crafts a narrative mosaic that explores themes of isolation, identity, death, and the longing for connection. The book’s strength lies in its ability to capture the intense, dreamlike quality of its setting, where the natural phenomenon of “white nights” serves as a backdrop for the characters’ introspective journeys. White Nights is a dark, lyrical exploration of the ways in which people seek meaning and belonging in a transient world.’

Mater 2-10 by Hwang Sok-yong (Korea), tr. Sora Kim-Russell & Youngjae Josephine Bae

– An epic, multi-generational tale that threads together a century of Korean history.

Centred on three generations of a family of rail workers and a laid-off factory worker staging a high-altitude sit-in, Mater 2-10 vividly depicts the lives of ordinary working Koreans, starting from the Japanese colonial era, continuing through Liberation, and right up to the twenty-first century.

‘A sweeping and comprehensive book about a Korea we rarely see in the West, blending the historical narrative of a nation with an individual’s quest for justice. Hwang highlights the political struggles of the working class with the story of a complicated national history of occupation and freedom, all seen through the lens of Jino, from his perch on top of a factory chimney, where he is staging a protest against being unfairly laid off.’

A Dictator Calls by Ismail Kadare (Albania), tr. John Hodgson

– A fascinating meditation on Soviet Russia, authoritarianism, power structures and a period of great writers.

In June 1934, Joseph Stalin allegedly telephoned the famous novelist and poet Boris Pasternak to discuss the arrest of fellow Soviet poet Osip Mandelstam. In a fascinating combination of dreams and dossier facts, Ismail Kadare, winner of the inaugural International Booker Prize, reconstructs the three minutes they spoke and the aftershocks of this tense, mysterious moment in modern history. Weaving together the accounts of witnesses, reporters and writers such as Isaiah Berlin and Anna Akhmatova, Kadare tells a gripping story of power and political structures, of the relationship between writers and tyranny.

‘The core of this brilliant exploration of power is an analysis of 13 versions of a three-minute telephone conversation between the Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin and the novelist Boris Pasternak in 1934. Each of these is an attempt to understand or justify Pasternak’s troubling, ambiguous response from a slightly different point of view. The book begins with what seem like autobiographical memories of Kadare’s time as a student in Moscow, setting a tone which hovers continually between fiction and non-fiction, between what is real and what is invented. Kadare explores the tension between authoritarian politicians and creative artists – it is a quest for definitive truth where none is to be found.’

The Silver Bone by Andrey Kurkov (Ukraine), tr. Boris Dralyuk (Russian)

– Inflected with Kurkov’s signature humour and magical realism, The Silver Bone crafts a propulsive narrative that bursts to life with rich historical detail.

Kyiv, 1919. The Soviets control the city, but White armies menace them from the West. No man trusts his neighbour and any spark of resistance may ignite into open rebellion. When Samson Kolechko’s father is murdered, his last act is to save his son from a falling Cossack sabre. Deprived of his right ear instead of his head, Samson is left an orphan, with only his father’s collection of abacuses for company. Until, that is, his flat is requisitioned by two Red Army soldiers, whose secret plans Samson is somehow able to overhear with uncanny clarity. Eager to thwart them, he stumbles into a world of murder and intrigue that will either be the making of him – or finish what the Cossack started.

‘A surprising book from Ukrainian novelist and journalist Andrey Kurkov, The Silver Bone is a crime mystery set in 1919 Kyiv during a time of chaos, shifts of power and random violence in the aftermath of war. But amidst the brutality is Kurkov’s sense of irony and absurdism. A young engineering student sees his father cut down by Cossacks and, moments later, a sabre cuts off his own right ear. He manages to catch it and keep it in a box, where it can still hear for him, wherever he is. Inspired by real-life, post-First World War Bolshevik secret police files, Kurkov’s novel creates an atmosphere that ranges from 19th century Russian literature to the immediacy of the current war in Ukraine, though it was initially published before Putin’s invasion.’

Undiscovered by Gabriela Wiener (Peru), tr. Julia Sanches (Spanish)

– A provocative, irreverent autobiographical novel that reckons with the legacy of colonialism through one Peruvian woman’s family ties to both colonised and coloniser.

Alone in an ethnographic museum in Paris, Gabriela Wiener is confronted with her unusual inheritance. She is visiting an exhibition of pre-Columbian artefacts, the spoils of European colonial plunder, many of them from her home country of Peru. Peering through the glass, she sees sculptures of Indigenous faces that resemble her own – but the man responsible for pillaging them was her own great-great-grandfather, Austrian colonial explorer Charles Wiener. In the wake of her father’s death, Gabriela begins delving into all she has inherited from her paternal line. From the brutal trail of racism and theft Charles was responsible for, to revelations of her father’s infidelity, she traces a legacy of abandonment, jealousy and colonial violence, and questions its impact on her own struggles with desire, love and race in a polyamorous relationship.

‘A compelling search for identity that explores the complicated relationship between the person you want to be and the stories of the past that might have made you. This is an exploration of colonialism’s surprising effects on a writer investigating her antecedents and ancestors starting from a display case of Peruvian artefacts in Paris and ending in a story of family, love and desire.’

The Shortlist

The shortlist of six books will be announced on 9 April 2024.

The winning title will be livestream announced at a ceremony on Tuesday 21 May 2024.

My Quiz Result

When I did the quiz for the first time, it came up with the result Undiscovered by Peruvian author Gabriela Wiener.

I did it a second time and I must have changed one of my answers and it came up with Not a River by Selva Almada. I have previously read and enjoyed one of her earlier novels The Wind That Lays Waste (my review here).

The good news is that I do have Not a River on my shelf because it is part of my Charco Press 2024 bundle, so I’ll be reading it next.

Many of these authors are new to me, though I have read Jenny Erpenbeck’s Visitation and Domenico Starnone’s Ties.

I will be looking out for Undiscovered to see if that quiz really does have any insight into my reading preferences! What book did it tell you to read? Let me know in the comments below.