In a rented room outside Plymouth in 1685, a daughter is born as her half-brother is dying. Her mother makes a decision: Mary will become Mark, and Ma will continue to collect his inheritance money.

Girls Initially Raised as Boys

As I began to read about Mary Read in Saltblood by Tasmanian author Francesca de Tores, I had a sense of deja vu. I paused reading and revisited my review of Irish author Nuala O’Connor’s Seaborne, another work of historical fiction, but focused on Kinsale born Anne Bonny.

Stories of Real Female Pirates

In Saltblood, we meet Mary Read (true historical figure), raised by her mother as Mark, a practical solution to poverty, inheritance laws and social restrictions.

After such a beginning, perhaps not surprisingly, Mary preferred for some years to live as Mark, due to opportunity and freedom. Working in service in a grand house as a man led to her/him enlisting in the Navy, then as the battles moved to land, joining the Army.

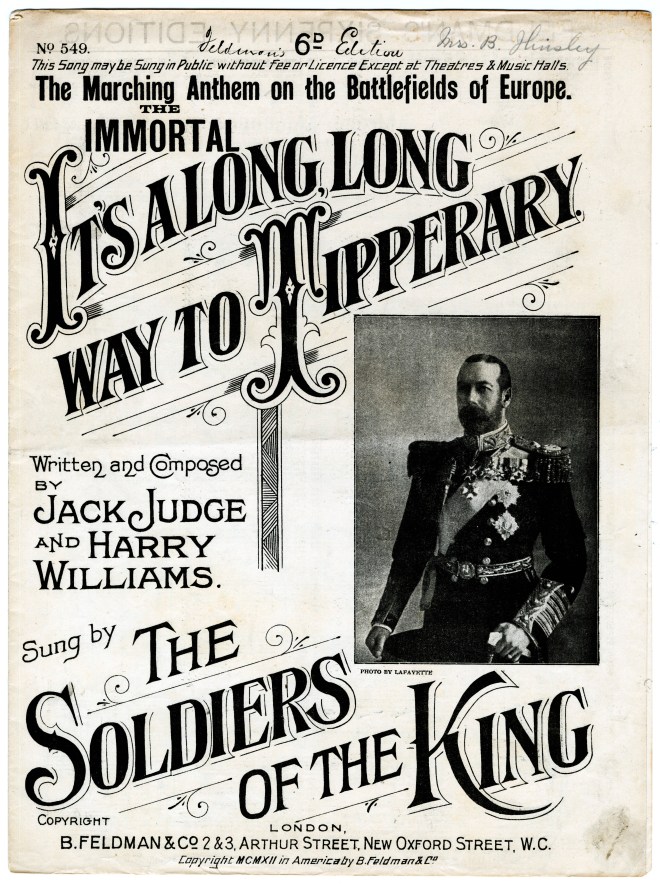

From the Military to Piracy

Settling for a short period as a married woman, she would then return to the sea after a tragic loss.

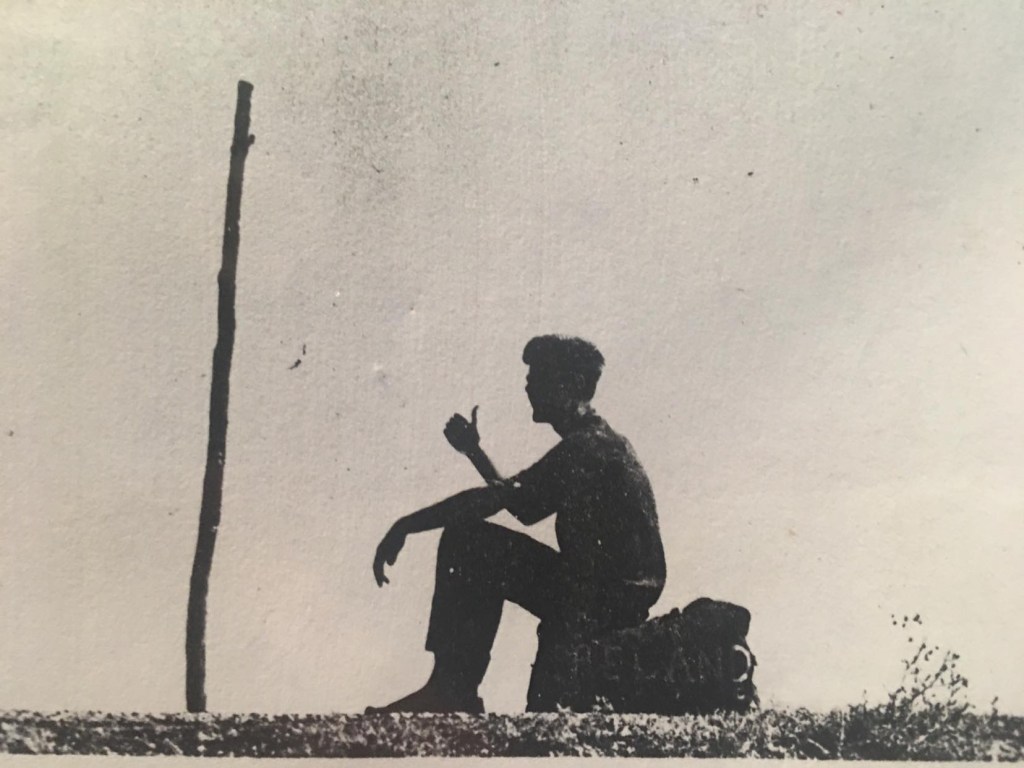

I went to sea a girl dressed as a boy, and I come back as something else entirely. I come back sea-seasoned: watchful of winds, and with an eye on the tides. I do not know if I have come back wiser, or better or perhaps madder. But I am not the same. What the sea takes, it does not return.

Initially working as crew for a privateer ship (authority sanctioned raiders); when they are raided by pirates, she elects to jump ship to escape the overly attentive Captain Payton and joins pirate Captain Jack Rackman. Although in her earlier years in the navy and army she was disguised, her later years at sea she presents as a woman, but is accepted as one of the crew due to her experience and abilities.

Pirating Protocols

Most pirates know the rules: go in fierce and fast, and the captains will beg for quarter, just as Payton did, and the Spaniards now do too.

One of the things the novel does well is really give you an idea of how pirating and raids work, for a start each member of the crew is made to sign a contract ‘articles of conduct’ that state policies around behaviour, pirate behavior (such as drunkenness, fighting, and interaction with women) and disciplinary action should a code be violated. Failing to honour the Articles could get a pirate marooned, whipped, even executed. It was the Captain’s way to maintain order and avoid dissent and ensure loyalty. The articles stated how gains would be shared.

There was a lot less fighting than we might imagine. Pirates preferred their target acquiesce. A black flag signaled to a vessel that they were about to be attacked, but that “quarter” would be given. This meant the pirates would not kill everyone on board if they cooperated and handed over any cargo. Seeing the black flag instilled fear and alerted ships to what was about to happen. If crew members did not fight, they might save their lives, but not their cargo. Crew sometimes elected to join the pirate ship as Mary did.

A Companion Crow

One of the interesting fictional elements in de Tore’s version of Mary Read’s life is the appearance of a crow that follows Mary on land and out to sea. The crows presence acts as a warning to the men, it is not a good sign to them, but for Mary, it’s presence is reassuring.

A bird that can pounce from the top of the mainmast to skewer a sardine in the water, or snatch a crab from under rock and find out its soft parts, is a bird that sees well, and clear. It counts, this witnessing. To live your life under the vigilance of a crow is a kind of covenant.

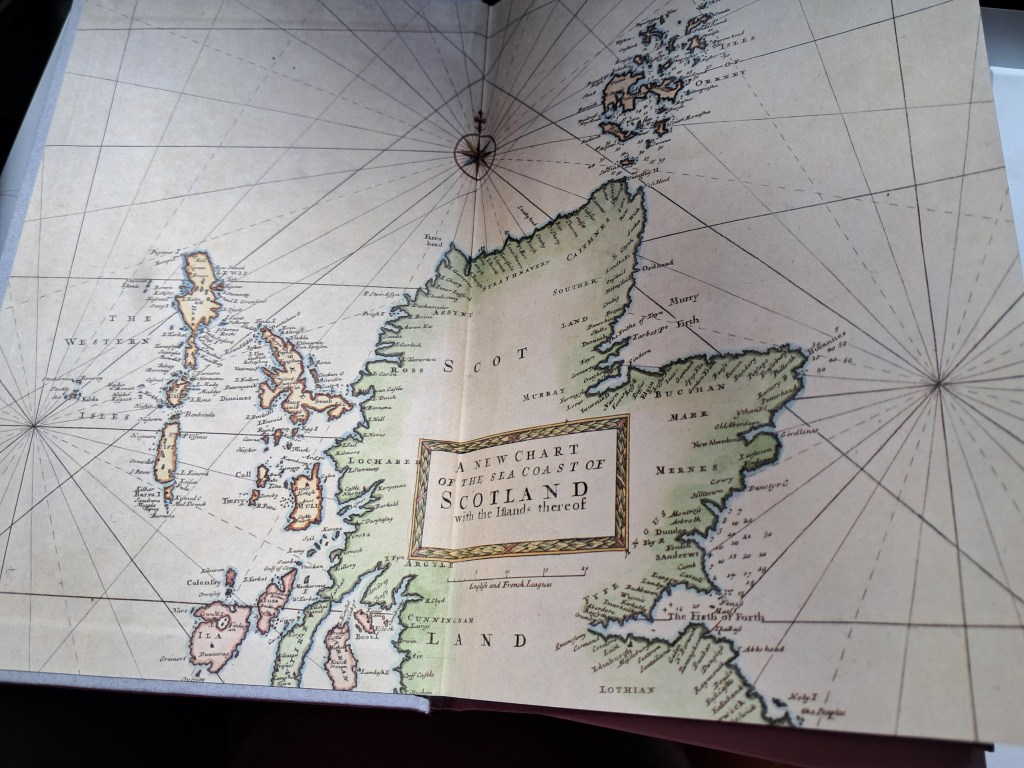

A Pirate Nest in the Bahamas

Nassau became the base for English privateers, many of whom became lawless pirates over time. The Bahamas were ideal as a base for pirates as its waters were too shallow for a large man-of-war but deep enough for the fast, shallow vessels favoured by pirates.

It was here that Mary Read eventually met and befriended the much younger (by 15 years), emboldened Anne Bonny, encountered in Seaborne by Nuala O’Connor. The two women became fast friends, though opposite personalities.

Anne falls for Captain Jack and decides to join the crew, deepening her relationship with Mary simultaneously.

Next to Anne Bonny, so bold and notorious, I had thought myself meek and colourless, and my story of little note. Yet she never tires of asking me about my years in the navy, and the army. Even my years on the Walcheren, which to me seem largely drab, fascinate Anne.

A Governor on a Mission

Saltblood continues to narrate the scrapes and adventures these two embark on and the efforts of Captain Rackham to avoid Governor Rogers, an English sea captain, privateer and colonial administrator who governed the Bahamas from 1718 to 1721 and again from 1728 to 1732. He aimed to rid the colony of pirates.

Initially I started then put this aside due to that feeling of having read something too similar, it starts off slowly and didn’t really pull me in, but more recently I picked it up again and continued only to find it much more engaging, as Mary is indeed quite a different character to Anne, and I enjoyed her land adventures as much as those at sea and the way their piracy days end is unforgettable.

After reading this I noticed I had another pirate book on my shelf, a work of history, The Stolen Village: Baltimore and the Barbary Pirates by Des Ekin, review coming soon.

Further Reading

Reviewed by Lisa at ANZ LitLovers

Author, Francesca de Tores

Francesca de Tores is a novelist, poet and academic. She is the author of five previous novels, published in over 20 languages, including Saltblood, which won the 2024 Wilbur Smith Adventure Writing Prize.

In addition to a collection of poems, her poetry is published widely in journals and anthologies. She grew up in Lutruwita/Tasmania and, after fifteen years in England, is now living in Naarm/Melbourne.