A Monument to Failure

Seventeen years ago, the author Rosa Ribas was taken by friends to visit a strange monument to a broken era in Seseña; it was a housing development known as ‘The Manhattan of La Mancha’.

Built in 2008, it was designed to house 40,000 people in 13,500 affordable apartments – a ready made settlement emerging from the dust-bowls of remote farmland 40 kilometres from Madrid. It now looked something like between an eerie ghost town and an abandoned building site.

One representation of many, it was a stark reminder of a housing bubble, burst by a rampant, unchecked building boom bust, and a global financial crisis that created an unprecedented unemployment rate and the deepest economic recession Spain had experienced for fifty years.

“When you walked around, you’d see the blocks where people were living, the blocks that were semi-inhabited, and then all the skeletons of buildings in different stages of completion,” she said. “From one day to the next, they told the workers not to come back the following day. And it all stayed like that.”

Holding On to Threads

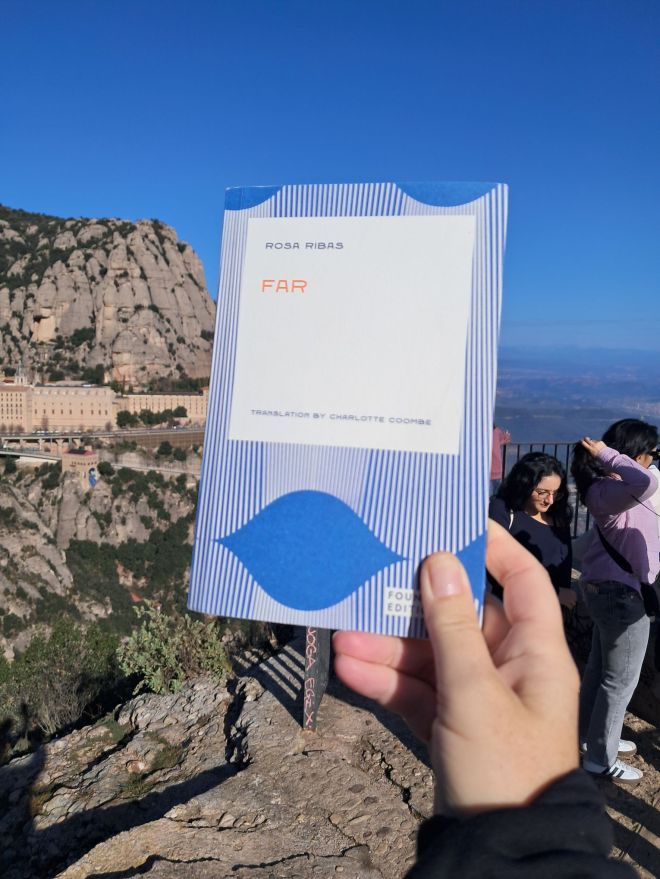

As night fell and three lights came, the realisation that they were the only people living there spawned the idea for a novel, Lejos in Spanish, now translated by Charlotte Coombe into English, brought to us by an excellent new imprint Foundry Editions, created in 2023 out of a love of these three things:

a love for discovering and sharing new voices, a love for the Mediterranean and the people and lands that surround it, and a love of internationalism and reading across borders.

The patterns on the covers of their books have been designed to capture the visual heritage of the Mediterranean. This one is inspired by the architecture of Santiago Calatrava’s City of Arts and Sciences in Valencia. It was created by Hélène Marchal.

Far, A Novel

I loved this novel, it is evocative of this semi-abandoned place, it depicts a demarcation between the legals and the illegals, the rightful inhabitants and the opportunistic outsiders, the followers of rules, those that want to make their own, and those that fall into the cracks.

The entire development was constructed on a pile of poorly concealed sleaze, a chain of bribery, corruption, intimidation, and complicit silences. No ancient manuscripts, no mythical foundations. If these lands had been the scene of some momentous event, back when battles of conquest and reconquest were being fought all over the area, no one had bothered to record it. It was a bleak place, devoid of stories, where it was impossible to satisfy any yearnings for greatness.

The entrance to the development still shows billboards offering apartments for sale, the middle one depicting the fugitive developer Fernando Pacheco in his suit and tie, the others depicting scenes of golfing, swimming pools and cocktails, a far cry from the reality within which they sat.

An Element of Noir, Foretold

The opening lines of Far stayed with me for the entire novel, they foreshadow the dénouement, a future turning point, that could even be the beginning of a follow up novel. For me it was a delightfully transgressive ending that I wasn’t even looking for, it arrived abruptly, though more regular readers of noir fiction might have seen it coming.

That night, he had no idea he was walking over a cemetery. A secret cemetery with no gravestones or crosses, and only two dead bodies. There would be three by the time he left.

The lyrical prose is clever, compelling and nothing is lost in translation.

The Lost and Fallen

We meet two unnamed characters, the first is the man we meet walking across that unconsecrated ground. He has just walked out of his office, his job, his life and is looking for a temporary refuge, when he remembers this place, this lost dream of many that one of his colleagues bought into. He needs to stay in hiding and at first is vigilant in keeping away from others, but the forced isolation and the desolate nature of the place loosen his discipline and he makes a friend in an older widower, Matias.

The second character is a woman living in one of the villas alone. Experiencing a double abandonment, she is sticking it out, she works from home and writes the minutes of the resident’s association meetings. Since the realisation that the development had truly been abandoned, the association had turned its focus onto other items.

Hegemons Harmony Hampered

Then, given the inhospitable environment, efforts became focused on the interior, on the decor of the apartments and villas. And on the “dignification” of the settlement. Swept pavements, manicured gardens. Being dressed properly in the street. “So, no more going out in your dressing gown to buy bread,” said Sergio Morales, the chairman of the residents’ association, at one of their meetings, in that jocular tone which often masks inconvenient or ridiculous orders.

In this place that promised a kind of utopia, those that bought into it begin to realise that they have become neighbours with the marginalised, as the unfinished houses become occupied by people in equally difficult, but entirely different circumstances and they don’t like it. They begin to obsess over it, becoming paranoid, arguing about whether to call the police or take care of things themselves.

The destruction of their fantasy, the deterioration of an imagined life, of people’s mental states and even their physical states, emulates the disintegration of the country’s economic situation, that contributed to the depth of suffering inflicted on the population, as millions of jobs were lost and opportunities for youth disappeared, creating a surge in racism and xenophobia.

Light Always Illuminates

And there, amid the chaos, insecurity and fear, unlikely friendships and connections develop, between the man and the widower on the unfinished side of the settlement, the woman from the deteriorating utopia on the other side and the Dominican who doesn’t ask questions, working at the petrol station.

Brilliantly told, infused with sardonic humour, it is a disturbing yet revelatory tale of what happens when severe change arrives unbidden and the effect it has on the ‘haves,’ the ‘have-nots’ and those that fall through the cracks in between.

Highly Recommended.

Further Reading

Article, Guardian: ‘Huge scars’: novelist finds a fractured Spain in its half-built houses by Sam Jones, July 2024

Article, Guardian: Building boom reduced to ruins by collapse of Spain’s economic miracle by Giles Tremlett, Jan 2009

Author, Rosa Ribas

Rosa Ribas was born in El Prat de Llobregat in 1963. She has a degree in Hispanic Philology from the University of Barcelona, and spent time in Frankfurt at the Goethe University and the Instituto Cervantes. She now lives and works in Barcelona again and the city plays a big role in her writing.

Rosa is widely considered one of the queens of Spanish noir, achieving critical and commercial success in Spain with her Dark Years Trilogy (Siruela) and her Hernández trilogy (Tusquets). Far is her first foray away from crime fiction, into a more menacing social commentary. It is her first book to be translated into English.

Translator, Charlotte Coombe

Charlotte Coombe translates works from French and Spanish into English. She was shortlisted for the Queen Sofía Spanish Institute Translation Prize 2023 for her co-translation of December Breeze by Marvel Moreno. In 2022 she won the Oran Robert Perry Burke Award for her translation of Antonio Diaz Oliva’s short story ‘Mrs Gonçalves and the Lives of Others’, and she was shortlisted for the Valle Inclán Translation Prize 2019 for her translation of Fish Soup by Margarita García Robayo.

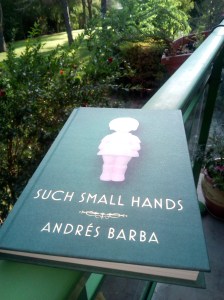

Such Small Hands is an incredible and unique novella, quite unlike anything I have read, it’s written almost from another dimension. The author somehow enters into a childlike perspective and witnesses the aftermath of a car accident in which the child Marina’s parents don’t survive.

Such Small Hands is an incredible and unique novella, quite unlike anything I have read, it’s written almost from another dimension. The author somehow enters into a childlike perspective and witnesses the aftermath of a car accident in which the child Marina’s parents don’t survive. Inspired by a disturbing event, this enters the realm of post trauma in an innocent and bizarre way, taking the reader back to a kind of twilight zone of an insecure childhood, where the nightmare becomes real and the line between reality and dreams is blurred.

Inspired by a disturbing event, this enters the realm of post trauma in an innocent and bizarre way, taking the reader back to a kind of twilight zone of an insecure childhood, where the nightmare becomes real and the line between reality and dreams is blurred.

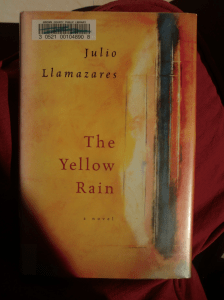

Her family, weathered by years of neglect, corruption and psychological torment, live in a claustrophobic environment that causes Andrea to develop her own eccentric behaviour in an effort to escape theirs. The house is inhabited by her two uncles, Juan and Roman, her aunt Angustias, the maid Antonia, and Juan’s wife, Gloria, plus a menagerie of cats, an old dog and a parrot.

Her family, weathered by years of neglect, corruption and psychological torment, live in a claustrophobic environment that causes Andrea to develop her own eccentric behaviour in an effort to escape theirs. The house is inhabited by her two uncles, Juan and Roman, her aunt Angustias, the maid Antonia, and Juan’s wife, Gloria, plus a menagerie of cats, an old dog and a parrot.