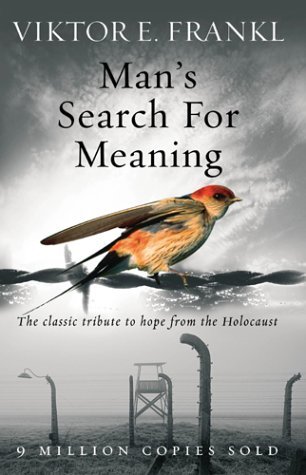

This long time classic, came up in conversation last week; a friend and I were talking about the inclination for one to want to ask, know or understand the ‘why’ when something bad happens.

For me, looking back at something challenging, I have a sense that when we cease to ask or need to know the ‘why’, that is a sign we have moved past or overcome it. How we get there is another subject altogether.

My friend then mentioned Viktor Frankl and interestingly, I learned he held a similar premise, but in the opposite direction. In terms of looking forward in life, we are likely to be more at peace and less prone to suffering if we have a ‘why’ in terms of our life’s meaning. So having our own ‘why’ is what we can focus on, looking forward, not back, at ourselves and not ‘the other’.

My friend then mentioned Viktor Frankl and interestingly, I learned he held a similar premise, but in the opposite direction. In terms of looking forward in life, we are likely to be more at peace and less prone to suffering if we have a ‘why’ in terms of our life’s meaning. So having our own ‘why’ is what we can focus on, looking forward, not back, at ourselves and not ‘the other’.

I decided it was time to dust off the book and retrieve it from my shelf.

In the first 100 pages Frankl shares some of his experiences and observations from being in Auschwitz and other Nazi concentration camps, with a focus on answering for himself the question of why some of them, like him, survived.

He identifies different turning points, observing the moment when some lost meaning and how those that did survive often had found a way to create it, despite the horrific circumstances.

His experience in Auschwitz, terrible as it was, reinforced what was already one of his key ideas. Life is not primarily a quest for pleasure, as Sigmund Freud believed, or a quest for power, as Alfred Adler taught, but a quest for meaning.

Frankl’s most enduring insight, one that resonates deeply:

forces beyond your control can take away everything you possess except one thing, your freedom to choose how you will respond to the situation. You cannot control what happens to you in life, but you can always control what you will feel and do about what happens to you.

Photo by Nina Uhlikova @ Pexels.com

The prisoner who lost faith in the future was doomed. Any attempt to restore a man’s inner strength had first to succeed in showing him some future goal.

Nietzsche’s words, “He who has a why to live for can bear with almost any how,” could be the guiding motto for all psychotherapeutic and psychohygienic efforts regarding prisoners. Whenever there was an opportunity for it, one had to give them a why – an aim – for their lives, in order to strengthen them to bear the terrible how of their existence.

Following this account of survival, in a short essay Frankl describes and discusses the therapy he was renowned for, one still practiced today:

Logotherapy in a Nutshell

Logotherapy focuses on the future, on the meanings to be fulfilled by a patient, a reorientation of sorts towards the meaning of a life.

Logotherapy tries to make the patient fully aware of his own responsibleness; therefore, it must leave to him the option for what, to what or to whom, he understands himself to be responsible. That is why a logotherapist is the least tempted of all psychotherapists to impose value judgments on his patients, for he will never permit the patient to pass to the doctor the responsibility of judging.

He writes of some of the methods used, citing examples as well as discussing the meaning of love and suffering.

“When we are no longer able to change a situation, we are challenged to change ourselves.”

It is a poignant read from a man who would embody his philosophy literally, leaving us with this enduring work and a therapy that is indeed a legacy and leaves us in no doubt as to the meaning and puspose of Viktor Frankl’s life.

Viktor Frankl

Viktor Emil Frankl, psychiatrist, was born March 26, 1905 and died September 2, 1997, in Vienna, Austria. He was influenced during his early life by Sigmund Freud and Alfred Adler, and earned a medical degree from the University of Vienna Medical School in 1930.

Viktor Emil Frankl, psychiatrist, was born March 26, 1905 and died September 2, 1997, in Vienna, Austria. He was influenced during his early life by Sigmund Freud and Alfred Adler, and earned a medical degree from the University of Vienna Medical School in 1930.

He founded the school of existential analysis, or logotherapy, which Wolfgang Soucek of the University of Innsbruck named “the third Viennese school of psychotherapy,” the other two being Sigmund Freud’s psychoanalysis and Alfred Adler’s individual psychology. Logotherapy was designed to help people find meaning in life.

By the time of his death, his book, Man’s Search for Meaning, had been published in 24 languages.

Further Reading

Logotherapy: How to Find More Meaning in Your Life by Emily Waters, PsychCentral

What is Logotherapy and Existential Analysis? by Alexander Batthyány, Viktor Frankl Institute

This was a compelling read in an interesting, dynamic format, a book length conversation between child psychiatrist and neuroscientist Bruce Perry and the well known broadcaster, philanthropist and show host, Oprah Winfrey.

This was a compelling read in an interesting, dynamic format, a book length conversation between child psychiatrist and neuroscientist Bruce Perry and the well known broadcaster, philanthropist and show host, Oprah Winfrey.

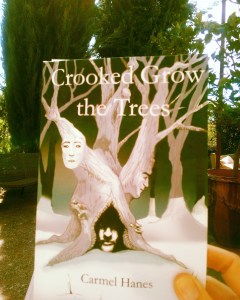

Crooked Grow the Trees is an engaging, insightful and well-informed read that I remain in awe of since I finished reading it. I bought it not long after an online group conversation on Goodreads with Carmel Hanes about Bernice L. McFadden’s

Crooked Grow the Trees is an engaging, insightful and well-informed read that I remain in awe of since I finished reading it. I bought it not long after an online group conversation on Goodreads with Carmel Hanes about Bernice L. McFadden’s

It’s a captivating read, enriched by experience that succeeds in presenting multiple moral viewpoints, forcing the reader to indulge and reflect on all perspectives and attitudes in the various conflicts. The conversations with each of the boys and the situations they respond to are brilliantly depicted, the dilemma feels real, the reader desperately wants them to succeed in being transformed.

It’s a captivating read, enriched by experience that succeeds in presenting multiple moral viewpoints, forcing the reader to indulge and reflect on all perspectives and attitudes in the various conflicts. The conversations with each of the boys and the situations they respond to are brilliantly depicted, the dilemma feels real, the reader desperately wants them to succeed in being transformed. James Doty never really set out to write this book, but he told his story to so many people with whom it resonated and being one of the founding creators of CCARE (The Center for Compassion and Altruism Research) he was eventually convinced how many more people could be inspired by his story and learn about the amazing work being undertaken, that he agreed to share his experience.

James Doty never really set out to write this book, but he told his story to so many people with whom it resonated and being one of the founding creators of CCARE (The Center for Compassion and Altruism Research) he was eventually convinced how many more people could be inspired by his story and learn about the amazing work being undertaken, that he agreed to share his experience.