There is nothing quite like a thoughtful work of nature writing to end the year with, as we move from autumn into winter hibernation. I missed out on the Nonfiction November themed reads that many other bloggers participate in, however I seem to have been attracted to reading nonfiction in December.

Best Nature Writing of 2025

I liked the sound of Raising Hare from the moment I heard of it, when it was longlisted and then shortlisted for the women’s prize for non-fiction. And in these last weeks of the year, it seems to be sustaining interest by readers, having won the Wainwright Prize for Nature Writing and Overall Book of the Year. The chair of judges, referring to it as a ‘soulful debut’ said,

“A whole new audience will be inspired by the intimate storytelling of Chloe Dalton. Raising Hare is a warm and welcoming book that invites readers to discover the joy and magic of the natural world. As gripping and poignant as a classic novel, there is little doubt this will be read for years and decades to come.”

Not a Typical Animal Rescuer

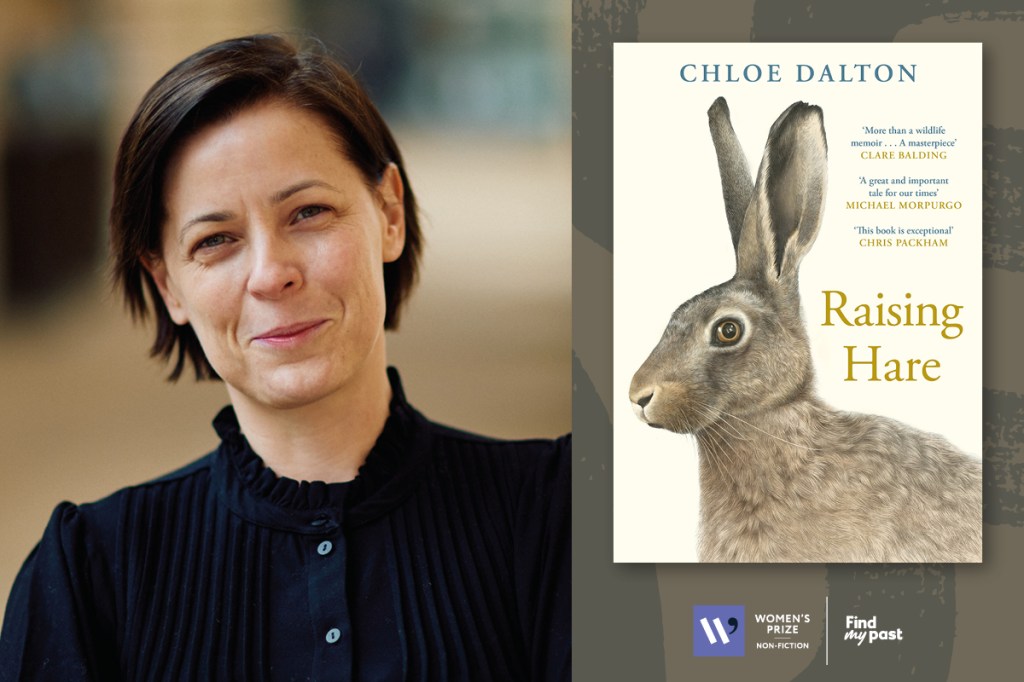

The author Chloe Dalton as we read in her short bio, does not have the typical profile of someone who might rescue an animal. She lived and worked in London as a political adviser and foreign policy specialist, something of a workaholic who travelled a lot and was always on hand when needed. So this story and transformation likely would not have happened, had there not been a lock down that sent her to her home in the English countryside and changed the way she lived and worked.

If I had an addiction, it was to the adrenaline rush of responding to events and crises, and to travel, which I often had to do, at a few hours notice.

It makes me wonder how many other unique experiences with nature and wildlife occurred during this time, when the world slowed down and people started noticing how we live and the detrimental impact we are having, even in a small acreage like this.

Born in a Pandemic

It’s the story of how a woman, living alone in the English countryside encounters a leveret after hearing a dog barking, clearly disturbing the nest. Initially ignoring it, then four hours later when it had not moved, she could not – the poor thing as small as the palm of her hand, frozen in the middle of a track leading directly to her house.

A call to a local conservationist dispelled any notion she had that she could return it to the field later, and further telling her hares could not be domesticated.

I felt embarrassed and worried. I had no intention of taming the hare, only of sheltering it, but it seemed that I had committed a bad error of judgement. I had taken a young animal from the wild – perhaps unnecessarily – without considering if and how I could care for it, and it would probably die as a result. My heart sank.

Overwhelmed and terrified she’d kill it by accident, she begged her sister, who lived with a menagerie of animals to take the leveret. After explaining how unsuitable that cacophonous environment would be for a baby hare, her sister told her ‘You’ll do fine’ and hung up.

Providing Care and Gaining an Education

We then observe where all that leads, not just into the care of a vulnerable animal, but how she educates herself all about leverets and hares, all the while focused on observing its every movement and behaviour, as they live alongside one another throughout the pandemic period and beyond.

I found it highly educational and loved the subtle transformation the author undergoes, as she learns to see her own environment through the purview of local wildlife and in effect provides an update to much existing research and knowledge about this breed, due to the unique opportunity of getting so close to living in proximity to a hare and her protege, while allowing it to stay wild so that it could continue to breed in the wild.

It is a gentle, enquiring, observational work of nature writing and a tender transformation of one human in her own ways, through the observation of the little known leveret, its home environment and habits. It is almost impossible not to be moved by the young hare, coming to know how sensitive the species is, and how it navigates this unorthodox contact with a female human.

I pondered the concept of ‘owning’ a living creature in any context. Interaction with animals nurtures the loving, empathetic, compassionate aspects of human nature. It taps into a primordial reverence towards the living world and a sense of the commonality and connectedness across species. It is a gateway, as I was discovering, into a state of greater respect for nature and the environment as a whole. We all too easily subordinate animals to our will, constraining or confining them to suit our purposes, needs and lifestyles.

Consciousness Raising Around Wildlife

What a chance to have occurred, for someone interested in policy, to take an interest in a more local and domestic situation, pouring herself into the research, taking care of a vulnerable sentient being and starting to consider the changes that can be made, to enable all species, including human to coexist in a less destructive manner.

Hares are the only game species which are not protected by a ‘close season’ in England and Wales: a period of the year during which they cannot be shot and killed. Other ‘game’ species – such as deer, pheasants and partridges, to name a few – are all protected by a close season. Hares by contrast can be shot at any time of year, including during the crucial months of February to September, when they typically raise their young.

Scotland and the rest of Europe already protect hares in this way. Only in England and Wales does this anomaly persist.

Highly Recommended.

Further Reading

Women’s Prize Interview: In conversation with Chloe Dalton

Read a Sample – the opening pages of Raising Hare by Chloe Dalton

Author, Chloe Dalton

Chloe Dalton is a writer, political adviser and foreign policy specialist. She spent over a decade working in the UK Parliament and the Foreign and Commonwealth Office and has advised, and written for and with, numerous prominent figures. She divides her time between London and her home in the English countryside.

Her debut book, Raising Hare, was an instant Sunday Times and New York Times bestseller. It won the Wainwright Prize for Nature Writing and was shortlisted for the Women’s Prize for Non-Fiction, and was selected as a Waterstones Book of the Year and as the Hay Festival Book of the Year. It was a Critics Best Books pick for The Times, Financial Times, Guardian, Spectator and iNews and was a Waterstones Non-Fiction Book of the Month.

‘Imagine holding a baby hare and bottle feeding it. Imagine it living under your roof, drumming on your duvet to attract your attention. Imagine the adult hare, over two years later, sleeping in the house by day, running freely in the fields by night and raising leverets of its own in your garden. This happened to me.’