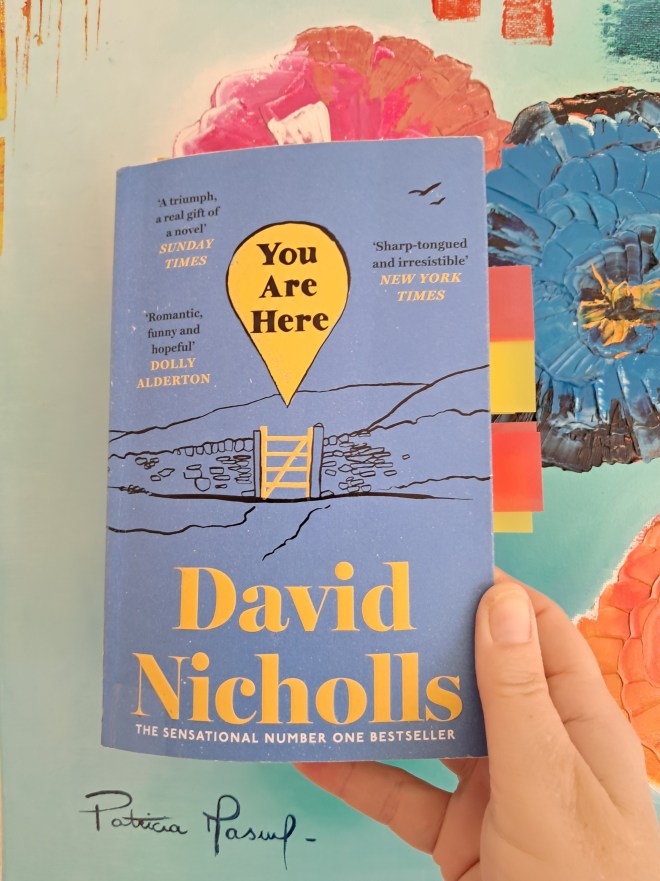

I picked this up from the library during the festive season for a light romcom type read without looking too much into what it was about. I remember when David Nicholls wrote One Day (2009), seeing that book splashed all over red double decker buses in London as if it were a movie, and it was a book. That was a book about two people from different backgrounds, barely connecting while at university, but keeping a tenuous friendships alive over 20 years. Emotional depth, continuity, the will they, won’t they get together intrigue – readers loved it.

Perfect Arc, Terrible Title

So I know he understands the formula, he is known to adapt books into screenplays, he’s got the story arc down pat. The only thing he gets wrong in my humble opinion are the totally forgettable book titles! And this one is terrible! You Are Here? I guess it could have been worse, Here is Now, or Another Day.

I was a little unsure going in, as I realised how lonely the two main characters were being portrayed, but then I remembered, they are going to be going through a transformation, so they must start out being somewhat at a loss. I persevered.

Northern England’s Coast to Coast

The book is about this one friend Cleo, who invites her friends Michael, Marnie, Conrad and her son Alex to go on a 2 or 3 day walk from the Cumbrian west coast of England inland, only Michael plans to go all the way west to east through Yorkshire to the opposite sea.

…he thought he could make it to the east, a high belt cinched under Scotland’s arm, crossing the Lakes, over the Pennines, along the Dales and across the Moors, then descending down the Yorkshire coastline to dip his toes into the North Sea. It was the famous route devised by Alfred Wainwright, 190 miles usually covered in twelve or thirteen days, though he felt sure he could do it in ten if he didn’t stop or rest.

When Freedom Beckons

As they set off, the weather deteriorates and some of them pull out, so then it is just Marnie and Michael who continue. She continues to delay her taxi and return train to London, enjoying the challenge, though at the back of her mind is a deadline for the copy edits she’s doing for an erotica novel, and at the back of his mind is a loose arrangement he made to meet the wife he separated from eighteen months ago.

Books saw her through the pupal stage of thirteen to sixteen, frowning at Kafka and Woolf, tearing through John Irving and Maeve Binchy, widely read in the proper sense, making no distinction between Jilly Cooper and Edith Wharton.

Marnie (38) is divorced and Michael (42) nearly 2 years separated, both are childless and while they say they were good with their solitude, the pandemic had not been exactly welcome, however this walking holiday does seems to be helping, lifting both their spirits.

Being with other families sometimes felt like indoctrination, as if she were attending a symposium on what family life could be. Here’s what you might have had if you’d made better choices, here’s where you might have poured your love.

After a slow and reluctant start, with their attention elsewhere, they begin to connect and are able to talk about things in a way they have not with anyone else – so it might seem predictable – but no, there has to be a deep connection, some kind of disruption, perhaps the feeling that’s it is over, and then the will they, won’t they, before the end.

‘Well, seven days! What did you talk about?’

‘You know – life, love, death,’ she said, and Conrad laughed, though in fact this had been true. ‘There’s something about walking, things slip out. It’s like taking a truth serum or something. Also it was very beautiful. Look.’

For two private people, the open air, the focus on the walking and the terrain facilitates them being a little vulnerable with each other (they are English, so not too much), while not quite being as open as good friends. That would require taking a risk, and neither are quite there yet.

I really enjoyed it, particularly towards the end as other elements in their lives began to put pressure on them, where they were likely to make mistakes, exposing their flaws, where they had to step up and beyond, because they couldn’t be guaranteed each other’s company like they had been on those seven days.

Apart from the English weather, it would be great to see this made into a film or series, it certainly lends itself to it, with the wry English humour and the opportunity to see all that beautiful landscape.

It reminded me a little of The Unlikely Pilgrimage of Harold Fry by Rachel Joyce, a character who walks from the south of England to the north, and interestingly she is also a playwright.

Recommended if you enjoy light, uplifting, humorous fiction that moves forward at a good pace.

Further Reading

The Guardian: You Are Here by David Nicholls review – a well-mapped romance

Author, David Nicholls

David Nicholls is the bestselling author of Starter for Ten; The Understudy; One Day; Us, which was longlisted for the Booker Prize for Fiction; Sweet Sorrow; and You Are Here.

He is also a screenwriter who has also written adaptations of Far from the Madding Crowd, When Did You Last See Your Father? and Great Expectations, as well as his own novels. His adaptation of Edward St Aubyn’s Patrick Melrose, starring Benedict Cumberbatch, was nominated for an Emmy and won him a BAFTA for best writer. Nicholls is also the Executive Producer and a contributing screenwriter on a new Netflix adaptation of One Day.