I first heard this recommended on the Irish Times Women’s podcast summer reads of 2025 and shortly after that it was longlisted for the Booker Prize 2025. It didn’t make the shortlist, but it was the novel I was most drawn to, given the adoption theme, but coming from a different culture than that we usually hear from.

Love

forms in the human body

– Louise Glück ‘The Fortress’

Forced Relinquishment Across Seas

A 16 year old living in relative privilege in Trinidad, has one crazy night out at carnival and months later is clandestinely bundled into various transportations, made to wait at different locations, never told where she is going, crossing the water to a hideaway in neighbouring Venezuela, where she will stay a while, give birth to her baby and return alone.

It was my father who made the arrangements. My uncle helped, since he lived down south, where all this kind of business is carried out. I’m talking south-south : down past the airport, past the swamp, past the oilfields, everything. Way down at the bottom of the island, down where Columbus landed, long ago.

Years later, 58 years old, living alone in London, unable to pick up her career in medicine, two grown sons, divorced, her family still in Trinidad, she begins to search for her lost daughter, with very little knowledge, except that memory of the trip in the dark. The rest must be imagined.

I’ve spent many hours trawling through images online, trying to find this place again.But Venezuela is a big country…Even now, over forty years later, I still don’t know exactly where I was.

Gone But Never Forgotten

The novel explores a certain way of living in Trinidad, a daughter made to feel shame, an event unspoken of for more than a decade, a self-exile imposed. A child never forgotten, forever part of her, out of reach.

Over the years, I’ve come across a few photos in magazines and newspapers that I’ve cut out and kept, because they look the way I imagine her to look. I have them in different ages.

Though she maintains contact with her family, there is more than just physical distance between them. There’s a loss of intimacy, of trust, a love that overnight became conditional, an imposed silence that is easier to bear from afar.

I do love my mother dearly, despite everything, but this particular issue is fraught for us. If she and I were to start talking, and I were to finally tell her the honest truth about everything I’ve felt over these past forty years? Well, I couldn’t do something like that – not now, at her stage of life.

There’s A Community Out There

Not until she begins her search and becomes familiar with the experiences of others like her, of children like the one she abandoned, does she begin to be able to understand what it is she has been feeling, a life long loss, momentarily offered the promise of being filled, as each potential contact (a woman her daughter’s age searching for their mother) raises that hope. She confides in a work colleague, a safe stranger.

‘I wasn’t going to tell you,’ I said. ‘But I guess, why not. Another person has been in touch. A girl. I mean, a woman. From the websites. As a possible, you know. Match.

He was watching me closely, and I tried to take on the right manner. Steady and controlled, hopeful but in a measured way. With a hint of detachment, as if I were talking about something at a much greater remove, of academic interest. I said she was in Italy, a town in the north, and that she was a professional person, a biochemist with a pharmaceutical company.

This was a compelling read that would create interesting discussions, with its deeply flawed characters, many terribly inhumane behaviours and the life long wounding adults commit, who care more for status and reputation than the damage heaped on women and children for being in the too common situation of being pregnant, or birthed, unwanted. It’s a conversation and narrative that has for too long been dominated by one side, so it is good to see it being explored through fiction.

This kind of story comes in so many varieties and though this one is unique, again it is driven by the shame and blame of young women, without consideration for those whose consent is never given, those future adults severed from the natural maternal bond and their lineage, conditioned into false belonging.

On the return journey, in the jeep and then in the dented, rattling airplane, I felt as if something had changed, although I couldn’t, at that stage, have fully articulated what it was. Pieces were beginning to settle in new patterns. Maybe my story wasn’t: Dawn, who made a mistake and brought shame to her family. Maybe its: Dawn, mortal woman, who took a wrong turn in life and got lost.

One of the most hopeful parts of this novel for me, was the knowledge that this character and this author, read the forums and the stories of the many humans born into this paradigm who write of their shared, common experience of how that separation affects a child, their life, their future relationships, which helps dispel the myth, that it’s a good or right thing to do, to sever any baby from its mother.

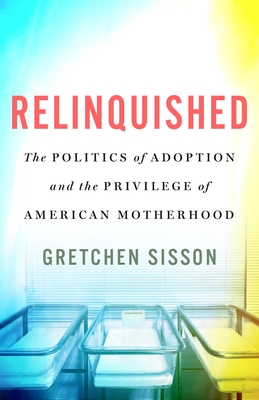

Last year, I read the book Relinquished by Gretchen Sisson, a non fiction work that was the result of ten years of interviews, research and analysis of young women who had given up their babies, looking back at the impact of those decisions.

If you have any interest in the subject of family preservation, and creating conditions where families are supported not separated, read this. If you want to know the truth behind the experience of relinquishing a child (a lifelong trauma), not to mention the impact that has on the child (loving family or not), become more well informed by reading this excellent work.

Further Reading

Read an Extract from the novel ‘Love Forms’ by Claire Adam

Guardian Review: Love Forms by Claire Adam, reviewed by Julie Myerson, June 2025

Recommended Resources : Adoptee Documentaries, Adoptee Podcasts, Adoptee Books

Recent Research: Relinquished: The Politics of Adoption and the Privilege of American Motherhood by Gretchen Sisson (2024)

Claire Adam, Author

Novelist Claire Adam was born and raised in Trinidad. She was educated in the United States, where she studied Physics at Brown University, and now lives in London with her husband and two children.

Her first novel, Golden Child, published in 2019, won the Desmond Elliott Prize, the McKitterick Prize, the Authors Club Best First Novel Award and was named one of the BBC’s ‘100 Novels that Changed the World’. Adam’s second novel, Love Forms, was longlisted for the Booker Prize 2025.

I wanted to explore the bond between mothers and their children. On one hand, it’s the most ordinary, mundane, taken-for-granted thing in the world… on the other hand, it’s deeply mysterious. In the case of a mother and child who’ve been separated since birth, for example, often there is a pull towards each other that lasts a whole lifetime. These are people who don’t know each other, who’ve basically never ‘met’ – and yet they yearn to be together. Why is that? Claire Adam

In A Sister’s Story, we encounter them again; the novel opens with the recall of a graduation celebration at Piero’s parent’s country home. Again the novel is narrated by the unnamed elder sister.

In A Sister’s Story, we encounter them again; the novel opens with the recall of a graduation celebration at Piero’s parent’s country home. Again the novel is narrated by the unnamed elder sister.

I admire the way Claire Keegan creates atmosphere and a sense of place, I could well imagine the small Irish town they lived, the cold, the workplace, the river – although I had to keep reminding myself it was the 1980’s and that there was electricity. Bill’s deliveries of wood and coal and the way the women made it feel like a much earlier era, though I don’t doubt it was freezing then as few could afford to heat their homes by other means.

I admire the way Claire Keegan creates atmosphere and a sense of place, I could well imagine the small Irish town they lived, the cold, the workplace, the river – although I had to keep reminding myself it was the 1980’s and that there was electricity. Bill’s deliveries of wood and coal and the way the women made it feel like a much earlier era, though I don’t doubt it was freezing then as few could afford to heat their homes by other means.

It made me recall another character, Albert, from the film

It made me recall another character, Albert, from the film  From the foundation of the Irish Free State in 1922 until 1996, at least 10,000 girls and women were imprisoned, forced to carry out unpaid labour and subjected to severe psychological and physical maltreatment in Ireland’s Magdalene Institutions. These were carceral, punitive institutions that ran commercial and for-profit businesses primarily laundries and needlework.

From the foundation of the Irish Free State in 1922 until 1996, at least 10,000 girls and women were imprisoned, forced to carry out unpaid labour and subjected to severe psychological and physical maltreatment in Ireland’s Magdalene Institutions. These were carceral, punitive institutions that ran commercial and for-profit businesses primarily laundries and needlework.

Meanwhile, her future adoptive mother, seven months pregnant with her first child had a kind of vision or strong premonition, in association with the Hindu Goddess Lakshimi, that there a baby girl coming to her, and insisted it wasn’t the baby she was carrying.

Meanwhile, her future adoptive mother, seven months pregnant with her first child had a kind of vision or strong premonition, in association with the Hindu Goddess Lakshimi, that there a baby girl coming to her, and insisted it wasn’t the baby she was carrying.

While every adoptee’s experience is different, there are so many aspects to the experience and responses to them that resonate with other adoptees, that reading a memoir like this can be very helpful, sharing experiences helps us understand.

While every adoptee’s experience is different, there are so many aspects to the experience and responses to them that resonate with other adoptees, that reading a memoir like this can be very helpful, sharing experiences helps us understand.

It is a very personal account and kudos to the author for having the courage to share it and inviting readers to go along on the emotional roller coaster of a journey it must have been.

It is a very personal account and kudos to the author for having the courage to share it and inviting readers to go along on the emotional roller coaster of a journey it must have been. Anne Heffron tells us it took her 93 days to write her book, but really it took a lifetime and she is to be commended for being able to complete it.

Anne Heffron tells us it took her 93 days to write her book, but really it took a lifetime and she is to be commended for being able to complete it.

A Girl Returned came to my attention because I like to see what

A Girl Returned came to my attention because I like to see what

My curiosity was peaked by a mini review over at

My curiosity was peaked by a mini review over at

A Memoir of Finding Home Across the World

A Memoir of Finding Home Across the World

Eventually she finds a way to navigate the two selves by turning the focus outward, towards helping others, addressing the ache of having had to suppress her true self for so long.

Eventually she finds a way to navigate the two selves by turning the focus outward, towards helping others, addressing the ache of having had to suppress her true self for so long. Immediately removed from everything familiar, home, school, church and community, she is sent in disgrace to her father’s new household and ordered to never go outside or if there was company, to remain in silence upstairs.

Immediately removed from everything familiar, home, school, church and community, she is sent in disgrace to her father’s new household and ordered to never go outside or if there was company, to remain in silence upstairs.