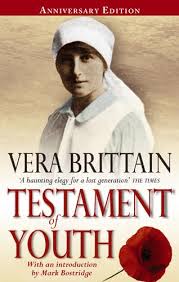

That Vera Brittain chose to name her autobiography a Testament, at first seems like an assertion of her intellectual inclinations, particularly in light of the decision she made to pause her hi-brow Oxford University studies when the First World War began as her closest friends, her fiancé Roland and brother Edward all signed up to participate, one by one departing for France.

That Vera Brittain chose to name her autobiography a Testament, at first seems like an assertion of her intellectual inclinations, particularly in light of the decision she made to pause her hi-brow Oxford University studies when the First World War began as her closest friends, her fiancé Roland and brother Edward all signed up to participate, one by one departing for France.

She had fought hard to be accepted into Oxford, at a time when women were not exactly welcome, her own family and many of their social peers thought it a waste of time. It remained important, but while those she was closest to were sacrificing everything, it felt indulgent to be pursuing anything intellectual. She volunteered to become a VAD (Voluntary Aid Detachment) nurse as she sought the diversion of physically demanding work to lessen the idle hours of mental anguish concerning her male contemporaries at war.

Testament is more than one woman’s intellectual account, it is evidence of a generation’s stunted youth, a youth stolen by war and loyalty, one that for the men who participated, would continue to be acknowledged and remembered, their efforts appreciated and honoured. For Vera Brittain it would bring grief, disappointment and disillusionment.

She recalled one of her last bittersweet moments, punting up the river in Oxford with her friend Norah, whom she would not see again after the end of that term.

‘No evening on the river had held a glamour equal to that one, which might so well be the last of all such enchanted evenings. How beautiful they seemed – the feathery bend with its short, stumpy willows, the deep green shadows in the water under the bank, the blue, brilliant mayflies which somersaulted in the air and fell dying into the water, gleaming like strange, exotic jewels in the mellow light of the setting sun.

I had meant to do such wonderful things that year, to astonish my fellows by unprecedented triumphs, to lay the foundations of a reputation that would grow ever greater and last me through life; and instead the War and love had intervened and between them were forcing me away with all my confident dreams unfulfilled.’

Her nursing efforts took her out of the northern provinces of England for good, away from her studies at Oxford to a military hospital in London, until events would propel her to volunteer for a foreign assignment, taking her to Malta and then close to the front line in France for the remaining years of the war.

Her account is all the richer for the journals she kept from 1913 to 1917 and rather than present them in full, she selects extracts to bring the era to life, sharing the angst and idealism of her youth, simultaneously looking back and narrating from the wisdom of early middle age, for she was 40 years old before she would finally see the much revised autobiography in print.

The book contains snippets of letters to and from Vera and her fiancé Roland and her brother Edward, they were her life blood, her motivation to face the relentless days in the hospital, where their work offered so much and yet did so little to stem the flow of blood and severed limbs, pain and hopelessness.

The letters that pass between Vera and Roland reveal the slow loss of hope, optimism and valour as they struggle to find meaning in war. Despite the often depressing content, they are fortunate to have each other, writing letters prolifically, drawing each other deeper into a love that they knew could be destroyed on any day.

After the war, Vera returns to Oxford and finds herself isolated. She has difficulty articulating her experience in a way that is understood and instead invites scorn and derision. A new generation of youth has swept up behind her and they have little time for the lessons that might be gleaned from a mature student who forsook her youth for volunteer nursing abroad. She gets involved in the debating society, and in one of the more excruciating passages in the book, valiantly tries to prove her point only to discover it will be she who is taught the lesson.

‘In the eyes of these realistic ex-High-School girls, who had sat out the war in classrooms, I was now aware that I represented neither a respect-worthy volunteer in a national cause nor a surviving victim of history’s cruellest catastrophe; I was merely a figure of fun, ludicrously boasting of her experiences in an already démodé conflict. I had been, I suspected, largely to blame for my own isolation. I could not throw off the War, nor the pride and the grief of it; rooted and immersed in memory, I had appeared self-absorbed, contemptuous and ‘stand-offish’ to my ruthless and critical juniors.’

Vera’s hope and her life purpose after the war, was to try to understand and then participate in any action that could prevent humanity from making the same terrible mistakes that caused the loss of so many lives. She changed her focus from Literature to History and searched for proof of anything that had been put in place to prevent such destructive hostilities from wiping out a generation of youth. She found what she was looking for in treaties and agreements and became an international speaker for the League of Nations attempting to advance understanding and awareness among the common population.

The book impressed me with its honesty, particularly as Vera Brittain was not afraid to portray her flaws; through the extracts from her journals we have a real sense of the character she was in her twenties and though she is the same person after the war and we recognise her inclinations, her direction in life is permanently altered by the experiences of those years.

The combination of experiencing the present through her diary and letters and her observations from the maturity of having survived war and gained some distance from it, from which to observe her former self, provides the reader a unique insight into humanity.

For me, it was a gripping read and although we learn much of the story in the opening introduction, it does nothing to lessen the effect as we witness Vera receiving news she has dreaded from the beginning and more than the individual events, the observation of emotional ups and downs and the effect of war on a generation seen from a young woman’s perspective is more insightful than any rendition of battles or victories I have ever read.

If the prospect of reading a 600 page book seems daunting, look out for the movie coming out in 2015!