Life and Death So Far, A Search for Meaning

“…we might remember the dead without being haunted by them, give to our lives a coherence that is not ‘closure,’ and learn to live with our memories, our families, and ourselves amid a truce that is not peace.” – Christian Wiman

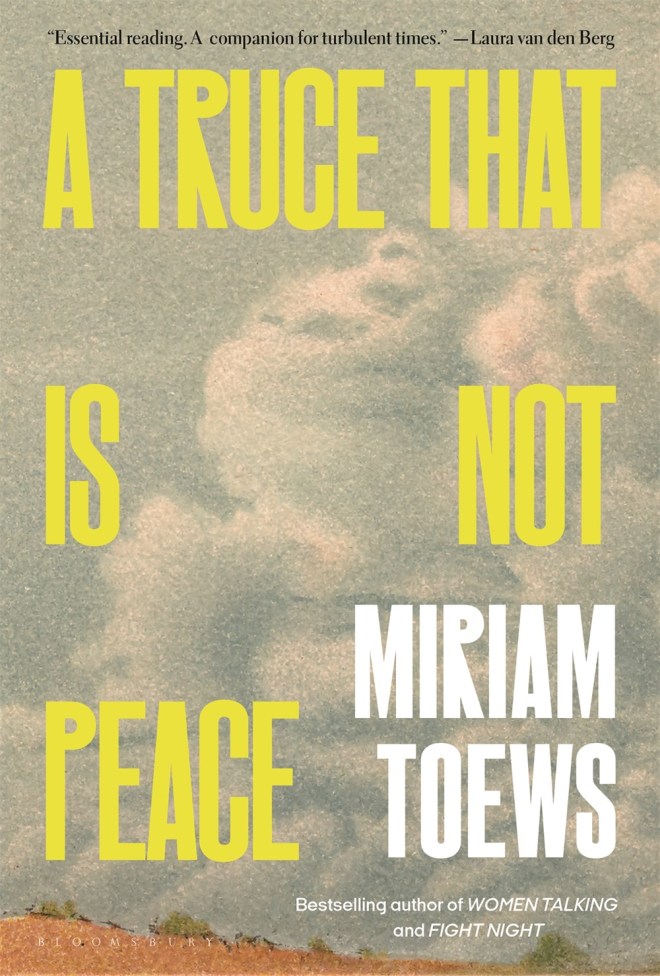

I’ve been tempted but never read any of Miriam Toews novels, so this might not be the best place to start, this being the first time she has written about her own life in non-fiction (Swing Low: A Life she wrote about her father in 2000). Hoever, I was intrigued and it was available to read on Netgalley so I jumped in to learn more about the source(s) of her inspiration.

While her novels are not autobiographies, they address the emotional, spiritual, and political terrain of her life – her Mennonite upbringing and their lack of voice, her family’s struggles with mental illness and the burden of communal silence.

A Truce That Is Not Peace makes those long-standing concerns fully explicit, acknowledging the reality behind those themes in her novels, exploring the writing life, family tragedies and day to day obsessions with grace, humour and bite.

Fragments of Memory, Flashes of Reality

The memoir is written in a fragmented journal entry style, one that continued to visit and revisit a number of current obsessions and memories she kept going back to, things from the past that haunted her, her father and sister’s suicides, their long periods of silence, their incessant need to write, her conversations and the questions asked by a Jungian therapist, who she reassures each visit that she is not suicidal (having read that is the greatest fear therapists have of their clients), though it is all she talks about.

It then switches into current desires, a wind museum idea, how to negotiate getting her royalties back from her ex-husband, and repeated attempts to answer the question Why Do I Write?, as the Conversación Comité who invited her to respond to that question, in anticipation of participating in a conversation in Mexico City, keeps rejecting her submissions as being not altogether what they were looking for, while attempts to rewrite it have her dreaming about her Wind Museum.

Creativity, the Messiness and Musings of Lives

Various quotes, letters, emails, dreams, nightmares; musings and memories litter the text as the author grapples with what presents itself in her life, and then the words of others arrive as if to provide validation or a way to get to that truce she seeks.

“Punishment, perhaps, or some contagion of fate, finds her here, her hair shorn, both wrists wrapped, her eyes open, pondering the parable of perfect silence.” – Christian Wiman

The text is interrupted by grandchildren activities, worries about biting habits, by questions she asks her mother, by the antics of family gatherings, of things falling apart in the house, the river that runs beneath it, a skunk with distemper that keeps trying to return to the now renovated back deck and falling into the window well. A close encounter with a plane in a blizzard on a highway, all while trying to find a way to navigate this life, this ‘truce that is not peace’.

It reminded me of reading Terry Tempest Williams When Women Were Birds: Fifty-four Variations on Voice, another memoir that circles a writer’s many obsessions as she struggles to find a connection. Her list of things she wrote of were: Great Salt Lake, Mother, Bear River Bird Refuge, Family, Flood, Cancer, Division of Wildlife Resources, Mormon Church, subjects that resided within her, evolving and changing shape like a murmuration.

When Miriam Toews makes her list she writes: Wind Museum, Deranged Skunk, North-west quadrant with ex, Conversacion in Mexico City, Neighbours.

I found the style confusing at first, but then because she returns to the same subjects, I started seeing the pattern. She mixes heavy subjects with the mundane of everyday life, and shares pockets of humour and tenderness amid the pain. The presence of children and noise and problems that need to be dealt with keep them all grounded and present and observant, there is inspiration everywhere, even in the most mundane.

While it may have helped had I read her other work, it is not necessary.

“When I started writing, the work was an act of rebellion. An act of subversiveness. But also a philosophical one. The humor, the writing, the taking note of absurdity. A rebelliousness against life. That’s how Camus felt too. That it is absurd. That there is no meaning. That there’s no reason to this crazy place of pain and ridiculousness. And yet, it’s what we have. So let’s be in it.” Miriam Toews

Further Reading

The Yale Review: Shakespeare & Company interview Miriam Toews on how writing resembles loss, Adam Biles

The Guardian: ‘My sister, my God. It’s a visceral pain that never goes away’: Miriam Toews on a memoir of suicide and silence by Hannah Kingsley-Ma

Author, Miriam Toews

Miriam Toews is a Canadian novelist and writer born in 1964 in Steinbach, Manitoba, a small, conservative Mennonite town that profoundly shaped her life and work.

Toews is best known for her darkly comic, deeply compassionate novels that explore themes of Mennonite culture, female autonomy, family bonds, mental illness, and the struggle for personal freedom. Her internationally acclaimed books include A Complicated Kindness (2004), All My Puny Sorrows (2014), and Women Talking (2018), the last of which was adapted into an Oscar-nominated film.

Much of Toews’s writing is informed by her own experiences, including the suicides of her father and sister, and her complicated relationship with the Mennonite community in which she was raised. Her memoir, A Truce That Is Not Peace, addresses these influences directly. She lives in Toronto.

“The book is about my attempt to find connection, to really meet my sister, in the spaces between words, in the silence. And my inability to do that, my reluctance to go there. There’s just such a huge abyss between the pain of the feelings and the articulation of that pain, whether it’s manifested in silence or whether it’s manifested in writing a story. It’s that time in between. I think that’s where I can maybe meet her in my mind.” interview with Adam Biles, Shakespeare & Company, Paris

N.B. This book was an ARC kindly provided by the publisher, 4th estate, via NetGalley.

A Woman on the Edge of Time is a memoir that reads like a mystery, as Jeremy Gavron, a journalist, interviews family, old school friends, neighbours and colleagues of his mother Hannah Gavron, whom he has little memory of.

A Woman on the Edge of Time is a memoir that reads like a mystery, as Jeremy Gavron, a journalist, interviews family, old school friends, neighbours and colleagues of his mother Hannah Gavron, whom he has little memory of.