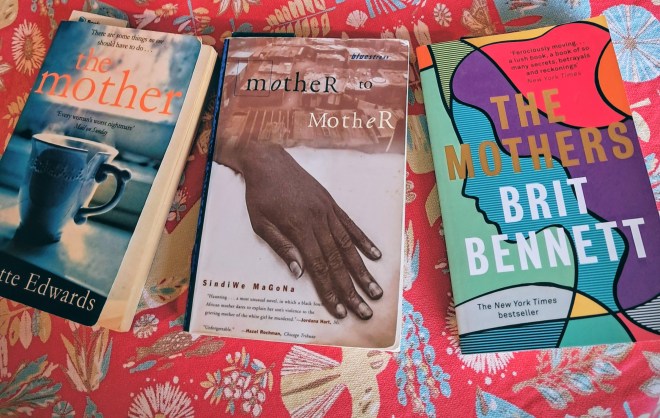

Mother to Mother is the second novel in my reading about the complexity of motherhood from three different perspectives, from within London’s Caribbean diaspora in The Mother by Yvvette Edwards, apartheid-era South Africa in Mother to Mother, and contemporary Black America in Brit Bennett’s The Mothers.

Making Sense of a Tragedy

Sindiwe Magona decided to write this novel when she discovered that Fulbright Scholar Amy Biehl, who was set upon and killed by a mob of black youth in August 1993, died just a few yards away from her own permanent residence in Guguletu, Capetown.

She then learned that one of the boys held responsible for the killing was in fact her neighbor’s son. Magona began to imagine how easily it might have been her own son caught up in the wave of violence that day.

The outpouring of grief, outrage, and support for the Biehl family was unprecedented in the history of the country. Amy, a white American, had gone to South Africa to help black people prepare for the country’s first truly democratic elections. Ironically, therefore, those who killed her were precisely the people for whom, by all subsequent accounts, she held a huge compassion, understanding the deprivations they had suffered.

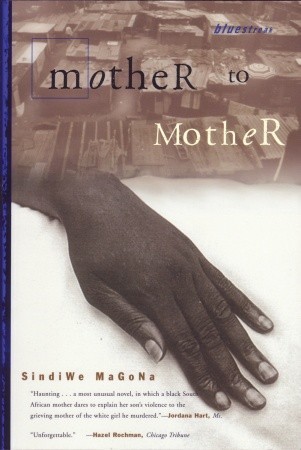

Mother to Mother, A Novel

When there are tragedies such as what happened here, usually and rightly, a lot is heard about the world of the victim, their family, friends, achievements and aspirations. The Biehl case was no exception.

Sindiwe Magona reflects and asks; are there no lessons to be had from knowing something of that other world, the opposite environments to those that grow and nurture the likes of Amy Biehl; to grow up under the legacy of apartheid, a society where you were born a second-class citizen, a system that relegated black people to the periphery and treated them as sub-human.

What was the world of this young woman’s killers, the world of those, young as she was young, whose environment failed to nurture them to the higher ideals of humanity and who, instead, became lost creatures of malice and destruction?

In reality, there were four young men, in the novel there is just one. Through the mother’s narrative of her life raising her children in this oppressive environment, through her memories, we come to understand a number of factors that contributed to the continuing dehumanisation of a population that became more and agitated as the little they had was taken from them, destroyed, bulldozed over and opportunities few and far between and one race of privileged people responsible.

Mandisa’s Lament

Mandisa, bewildered and grief-stricken, on learning the news of her son’s involvement in this terrible tragedy, mines her memory and reflects on the life her son has lived, that brought them to this moment. In looking for answers she paints a vision of her son and his world, the world she has inhabited and done her best to navigate and lead her children through, as if in conversation with that other mother, the one who has lost a daughter, forever.

Forced Removals

What began as a rumour, that the government was going to forcibly remove all Africans from numerous settlements to a common area set aside for them all was initially laughed off, not believed. Everyone talked about it, but not with concern, it was impossible.

There were so many of us in Blouvlei, a tin-shack location where I grew up, Millions and millions. Where would the government start? Who could believe such a thing?

The sea of tin shacks lying lazily in the flats, surrounded by gentle white hills, sandy hills dotted with scrub, gave us (all of us, parents and children alike) such a fantastic feeling of security we could not conceive of its ever ceasing to exist. This, convinced of the inviolability offered by our tremendous numbers, the size of our settlement, the belief that our dwelling places, our homes, and our burial places were sacred, we laughed at the absurdity of the rumour.

But the government was not laughing. When the rumour paled and was all but forgotten, one day if returned with a deafening roar, as an aeroplane dropped flyers warning them all of the impending deadline, that they would be forcibly removed. To Guguletu.

A grey, unending mass of squatting structures. Ugly. Impersonal. Cold to the eye. Most with their doors closed. Afraid.

Oppressed by all that surrounds them…by all that is stuffed into them…by the very manner of their conception. And, in turn, pressing down hard on those whom, shameless pretence stated, they were to protect and shelter.

Segregation was enforced and black people were removed from their settlements, from suburbs where only white people would now live, pushed into a place and among people they did not know, in challenging conditions and the need to find work.

On A Dark Day, Resentments Build

The narrative is written in two timelines, the day of the protest, when Mandisa is sent home early from her job as a cleaner in a white woman’s home, due to the unrest – interspersed with memories of how their lives came to arrive at this point. She waits and waits for her son to come home and becomes increasingly concerned at his lack of appearance.

10.05 PM – Wednesday 25 August 1993

…where was Mxolisi? Not for the first time, I asked myself what it was that made him so different from the other two children… What had made Mxolisi stop confiding in me? And when had that wall of silence sprung between us? I couldn’t remember. He used to tell me everything…and then, one day I woke up to find I knew almost nothing about his activities or his friends.

As the family circumstances are shared and the life of this mother is revealed, I am reminded of the two autobiographies I have read, of the similarly challenging life and raising of her own children the author in similar circumstances. Although this is fiction, there is resemblance to her own circumstances, no doubt the reason why she understands this could so easily have been any one of those mothers in their neighbourhood.

The story leads up to the actual event, to what occurred on that day, the clash, the terrible crossing of paths, of being in the wrong pace at the wrong time, the burning hatred of an oppressor, the innocent face of one who looked like them, the dark desire of a race seeking revenge, the deep resentment of decades expressing itself in rage.

My son, the blind but sharpened arrow of the wrath of his race.

Your daughter, the sacrifice of hers. Blindly chosen. Flung towards her sad fate by fortune’s cruellest slings.

It is a courageous attempt to present a community in the grip of violent rage, to allow the voice of a mother to speak and share the growth of a family, the intense pain of all touched by a tragedy, to consider a path of redemption, to learn something from it. There may not be any conclusions, but perhaps we are all, all the better for being open to listen to the mothers, to find empathy for people doing the best they can in challenging circumstances. A thought provoking, powerful read.

Restorative Justice

In a final end piece to the story of Amy Biehl, after four men were convicted and given 18 -year prison sentences, there was in July 1987, an appearance before the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s amnesty committee to argue for their release from prison, due to the politically motivated nature of the crime.

The parents, the Biehl’s attended the trial and shook hands with the parents of all four men. They understood the context of the South African struggle better than many South Africans.

The men spoke and asked for forgiveness. After consideration, all four were pardoned and the Biehl family supported their release.

Linda and Peter Biehl created a humanitarian organisation, the Amy Biehl Foundation Trust to develop and empower youth in the townships, in order to discourage further violence.

Two of the men who had been convicted of her murder went on to work for the foundation as part of its programs.

Further Reading

Amy Biehl’s Last Home: A Bright Life, a Tragic Death, and a Journey of Reconciliation in South Africa by Steven D. Gish

South African Press Association: Excerpts from SAPA Coverage of Biehl Amnesty Trials

Author, Sindiwe Magona

Sindiwe Magona (born.1943) a graduate of Columbia University, is an author, poet, playwright, storyteller, actor, and inspirational speaker. Magona retired from the United Nations, where she worked in the Anti-Apartheid Radio Programmes until June 1994 and UN Film Archives till her retirement. After twenty-five years in New York, she relocated to her home country, South Africa.

Her writings include To My Children’s Children and Forced to Grow (autobiography); Living, Loving, and Lying Awake at Night and Push-Push and Other Stories (short stories).

Her novels are When the Village Sleeps, Mother to Mother, Beauty’s Gift, Life is a Hard but Beautiful Thing (YA) and Chasing the Tails of My Father’s Cattle! Please, take photographs! a book of poetry, Modjaji Books and Awam Ngqo,(short stories) and Twelve Books of Folktales – written in both English and Xhosa.

Magona has written over a 120 children’s books, including: The Best Meal Ever and Skin We Are In and Her awards include include Honorary Doctorates from Hartwick College, USA; Rhodes University; and Nelson Mandela University; and the Order of iKhamanga.

My writing, on the whole, is my response to current social ills, injustice, misrepresentation, deception – the whole catastrophe that is the human existence. Sindiwe Magona

Next Up, the third novel : The Mothers by Brit Bennett

Finding herself unemployed and pregnant with her third child after being pushed out of a teaching job – her husband’s parting shot as he abandons his young family, to inform her employer of his disapproval (a husband’s approval was required for a married (black) woman to be eligible to work) – she reinvents herself, creating her own work (selling sheep heads (cooked) she’d bought on credit) initially to survive, determined to reinstate herself back into the teaching profession, to extend and elevate her education and move beyond surviving to thriving.

Finding herself unemployed and pregnant with her third child after being pushed out of a teaching job – her husband’s parting shot as he abandons his young family, to inform her employer of his disapproval (a husband’s approval was required for a married (black) woman to be eligible to work) – she reinvents herself, creating her own work (selling sheep heads (cooked) she’d bought on credit) initially to survive, determined to reinstate herself back into the teaching profession, to extend and elevate her education and move beyond surviving to thriving. Pursuing a higher level of education to offset so much else that set her back, fed into Magona’s ambition; as she achieved, her self belief grew and she pushed herself further, while assuming the role of both parents.

Pursuing a higher level of education to offset so much else that set her back, fed into Magona’s ambition; as she achieved, her self belief grew and she pushed herself further, while assuming the role of both parents. I was reminded of my recent read of Riane Eisler and Douglas Fry’s

I was reminded of my recent read of Riane Eisler and Douglas Fry’s  The slim autobiography shares stories from her childhood up to the age of 23, all of it taking place in South Africa. In her early years, as was customary among amaXhosa people, she lived with her grandparents. It was often the case while parents were trying to earn a living in starting a new life, that the extended family and home community was the safest, most caring environment for young children to be. There was always someone to look after children, they had food, shelter, company and they thrived.

The slim autobiography shares stories from her childhood up to the age of 23, all of it taking place in South Africa. In her early years, as was customary among amaXhosa people, she lived with her grandparents. It was often the case while parents were trying to earn a living in starting a new life, that the extended family and home community was the safest, most caring environment for young children to be. There was always someone to look after children, they had food, shelter, company and they thrived.

Magona was born in 1943 in the small town of Gungululu near Mthatha, in what was then known as the homeland of Transkei, in the Eastern Cape of South Africa.

Magona was born in 1943 in the small town of Gungululu near Mthatha, in what was then known as the homeland of Transkei, in the Eastern Cape of South Africa.