Back in 2023 Irish author Elaine Feeney’s novel How To Build a Boat (my review) was longlisted for the Booker Prize and shortlisted for the Irish Book Awards. That was a bumper year for Irish novelists with four of them on the longlist and Paul Lynch’s Prophet Song winning the prize.

How to Build a Boat was a great read with interesting, memorable characters, about an oppressive school and a free spirit whose presence disturbed the controlling order and rigidity of the institution by making a boat inside the school walls.

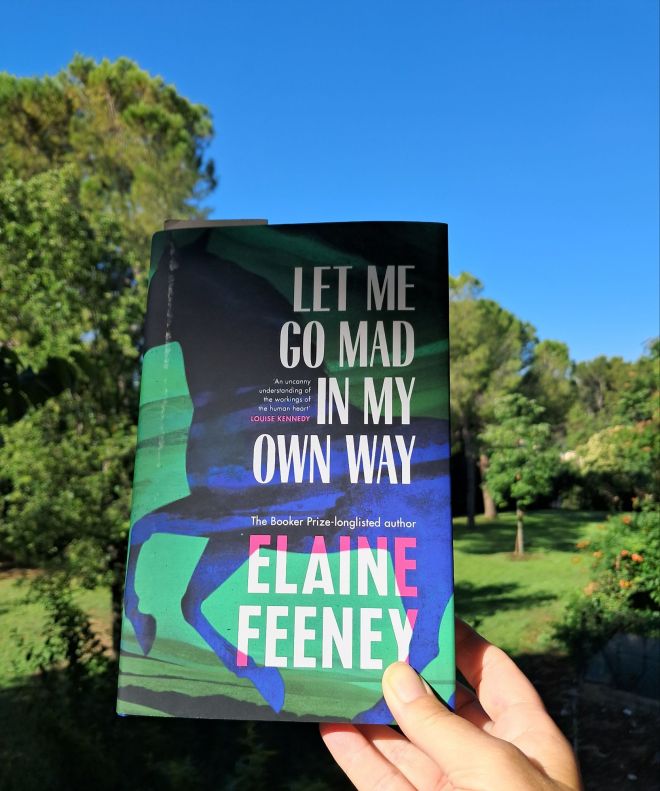

When I saw she had another book out with a provocative title like this, I decided to dip in and see what it was about.

French and Greek Literary References, The Female Voice

If the title isn’t a giveaway to reclaiming and redefining madness, a convenient label historically used to oppress women and have them incarcerated in the past, the epigram from Annie Ernaux’s novella Shame further reminds us of the often silenced, lived experience of women and girls, peeling back social shame, intergenerational violence and little recognised, inherited trauma that continues to reverberate and affect current behaviours and relationships.

This can be said about shame: those who experience it feel that anything can happen to them, that the shame will never cease and that it will only be followed by more shame. Annie Ernaux, Shame

A Story In a Title

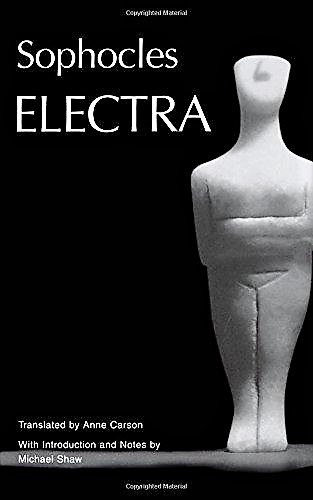

The title of Feeney’s book is a powerful statement from the ancient Greek playwright Sophocles. The line appears in his play Electra, translated as: “I ask this one thing: let me go mad in my own way.” In the play, the main character, overwhelmed by grief, injustice and familial violence, demands to grieve and rage on her own terms. It is a cry for the right to express and feel one’s own emotional suffering and pain, in the way it is desired, needed.

“Don’t tell me how to feel or how to react, let me experience my madness as I must.”

Elaine Feeney said in an interview that she encountered the phrase in Anne Carson’s translation of Electra and immediately felt its resonance, both personally and within her book’s themes.

Going Mad or Getting to Grips With the Past

Her novel is about an Irish woman named Claire O’Connor who had been living in London with her boyfriend Tom Morton, unravelling after the death of her mother. Unable to cope, she breaks up with Tom and returns to the West of Ireland, initially to care for her father.

Back living in the family home awakens memories and issues for Claire and her two brothers, who are more used to avoiding and ignoring past and present bad behaviours.

The unexpected arrival of Tom and new friends Claire makes at her new university job, create a situation that brings people together that wouldn’t ordinarily meet.

Choosing to Live Differently

This new dynamic challenges some of those repressed feelings and the characters will either continue to deny or choose to grow.

‘There’s land here, isn’t there?’ He was playing with me now. ‘They’re not making any more of it – I’ll bet they don’t teach you that inside in the universities.’

I wanted to say that none of us wanted his land, full of rock, thistles and furze bushes. That it was a noose. I wanted to say the land was never mine. I knew well enough to know that.

Generational Influence

The story is told in different timelines, in the first person present, when Claire is an adult and has returned to Ireland, in 2022 and then there are chapters about the family from 1920, events around the old abandoned house at the back their property.

The O’Connor’s were good tenant farmers and had then been given this small handsel of land, a slight acreage of a holding from the Estate in the Land Commission’s Exchange for compliance. They had, until this, been generations of shepherds. Mostly, too, they were emigrants. A compliant people who believed in God being good and work being eventually rewarded for all eternity.

1920 was a period when there was unsettling violence from the Black and Tan Forces in East Galway around the Irish War of Independence, cultivating an atmosphere of fear and violence and an era where there was little escape, and few and far opportunities. Though 100 years in the past, undercurrents of that violent era continue to pump through the veins of this family.

Then there is Claire’s childhood memory of a Hunt Day in 1990, when the Queen of England was looking for a black mare for the Household Cavalry. Flashes of memory bring it all back as Claire confronts the past in order to better create any chance she might have of a better future.

Great Storytelling and Thought Provoking Depth

It is a thought provoking novel rooted in personal, collective and inherited memory, that deals with ‘the home‘ as the institution that requires dismantling, and it is the coming together of family, friends and the new relationships in Claire’s life that will facilitate the change that can redefine what home can become.

It’s also a novel that is entertaining with or without the layers of meaning that come from the references, but it is one that I have enjoyed all the more for understanding more about the motivations of the author and the literary influences she has referenced and talks about in the following interview.

And speaking of the Booker Prize, the longlist for 2025 will be announced on Tuesday 29 July 2025. This year’s Chair of Judges is an author who has never been in a book club, Roddy Doyle, who is joined by Booker Prize-longlisted novelist Ayọ̀bámi Adébáyọ̀; award-winning actor, producer and publisher Sarah Jessica Parker; writer, broadcaster and literary critic Chris Power; and New York Times bestselling and Booker Prize-longlisted author Kiley Reid.

Further Reading or Listening

An Interview by Bad Apple, Aotearoa: Ash Davida Jane interviews Elaine Feeney

Listen to Elaine Feeney read an extract from her novel Met Me Go Mad In My Own Way

Elain Feeney, Author

Elaine Feeney is an acclaimed novelist and poet from the west of Ireland. Her debut novel, As You Were, was shortlisted for the Rathbones Folio Prize and the Irish Novel of the Year Award, and won the Kate O’Brien Award, the McKitterick Prize and the Dalkey Festival Emerging Writer Award. How to Build a Boat was also shortlisted for Irish Novel of the Year, longlisted for the Booker Prize, and was a New Yorker Best Book of the Year.

Feeney has published the poetry collections Where’s Katie?, The Radio Was Gospel, Rise and All the Good Things You Deserve, and lectures at the University of Galway.